The short film SHELTER, from California-based Reneff-Olson Productions, features dancers from across the world. It was made in response to the difficult situation in which performers find themselves at the moment during the COVID-19 crisis. The production company is headed by siblings Alexander and Valentina Reneff-Olson and, speaking of the making of SHELTER, Alexander Reneff-Olson said:

I wanted to bring attention to the current realities performing artists are facing during this time. Self-isolation has kept dancers from performing in conventional ways and traditional venues, but it hasn’t diminished their resilience, even in the face of these unprecedented times.

You might be surprised at the number of people who are involved in SHELTER who have strong connections with Australia and New Zealand. I was when it was suggested by a colleague from San Francisco that I take a look.

First up is perhaps Danielle Rowe, former principal with the Australian Ballet. After leaving Australia, Rowe has had a varied career, first with Houston Ballet, and then Nederlands Dans Theater and various other companies. She is now well into a career as a choreographer. Her work Remember, Mama, for Royal New Zealand Ballet’s 2018 program Strength and Grace, was reviewed on this site by Jennifer Shennan. Read that review at this link. Rowe is currently choreographing a production of The Sleeping Beauty for Royal New Zealand Ballet. It is due to open in October (provided that is a possibility given current restrictions).

For SHELTER, Rowe worked with Garen Scribner, a New York-based actor, dancer and singer, on the choreography and the casting of the dancers who appear in the SHELTER. And, as Alexander Reneff-Olson has commented, Rowe also ‘selected and assigned sections of the choreography to each dancer and provided artistic feedback as the editing progressed’.

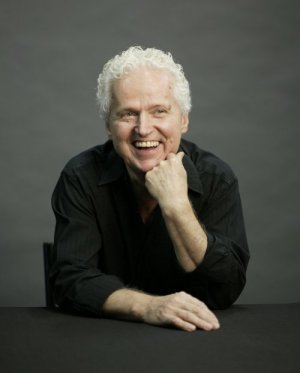

Australian Ballet principals, Amber Scott and Ty-King Wall, also appear, as does Artistic Director designate David Hallberg. Then there are Australians who no longer dance in Australia but are busy making exceptional careers elsewhere in the world. They include Benjamin Ella, currently a soloist with the Royal Ballet in London, and Jared Wright, at present a soloist with Dutch National Ballet in Amsterdam. Royal New Zealand Ballet principal, Nadia Yanowksy, seen in the image above, is also featured in SHELTER.

The project grew from an earlier work called Hey Mami co-choreographed and performed by Rowe and Scribner in 2015. But the idea grew to include 26 dancers and, as Alexander Reneff-Olson explains:

Dani and Garen assigned specific time-codes from Hey Mami for each dancer to learn and film themselves performing, and they offered to virtually rehearse individually with any dancers who wanted to.

The individual segments were then edited by the Reneff-Olson team.

SHELTER also has some quite beautiful scenes shot on the stage of an empty San Francisco War Memorial Opera House. Alexander Reneff-Olson explains:

The city and County of San Francisco gave about a 12 hour advance warning on the shelter-in-place order taking effect, and we used some of that time to capture what footage we could of Joseph Walsh [a principal with San Francisco Ballet] in the War Memorial Opera House, the home of San Francisco Ballet.

The full video can be viewed at this link where you will also find credits and a full list of the dancers who appear.

Michelle Potter, 20 May 2020

With thanks to Kate McKinney of San Francisco Ballet for putting me in touch with Alexander Reneff-Olson, and Renee Renouf Hall for suggesting I take a look at SHELTER.

Featured image: Promotional image for SHELTER.