Dance Australia‘s annual ‘Critics’ Survey’ was published in this year’s first issue (January/February/March 2025). The survey is always a good read with its breadth of coverage and its varied views of the year’s best productions. In addition to my report, headed as ‘Michelle Potter (Canberra and elsewhere)’ on pp. 32-33, critics represented this year are Lisa Lanzi (Adelaide), Denise Richardson (Brisbane), Rhys Ryan (Melbourne), Nina Levy (Perth), and Geraldine Higginson (Sydney).

I began my contribution with some remarks about reviews in general, which I have also addressed elsewhere on this website. Those remarks deal specifically with an issue regarding critics and reviews that I continue to find frustrating and annoying—who can and who can’t review a show according to some involved with a production. I followed up with a general comment about dance in Canberra and I noted that I frequently travel outside of Canberra to see works I otherwise would miss, hence the ‘and elsewhere’ that follows ‘Canberra’ in the heading to my Dance Australia remarks. Finally I chose the show I think outclassed all others (others that I was able to see of course).

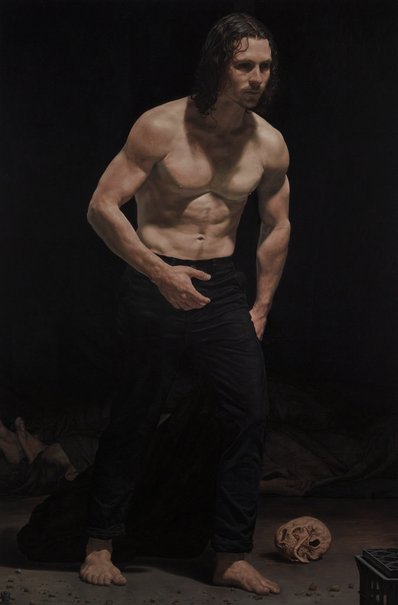

I don’t yet have a good quality PDF file of my contribution so I have posted a text version below. An image of a moment from Queensland Ballet’s production of Coco Chanel. The life of a fashion icon was published with my survey remarks and I have used it as the featured image for this post.

Here is the text:

‘I have a major gripe. Twice in 2024 I was offered complimentary tickets to a production but was invited to come and ‘enjoy’ the show but not to write a review. Both productions were in Canberra with one by a Canberra-based organisation. In both cases I did not accept the complimentary ticket with its attached condition. My gripe focuses on the right to decide whether reviews can or cannot be written about specific performances that are open to the public? Who has that right?

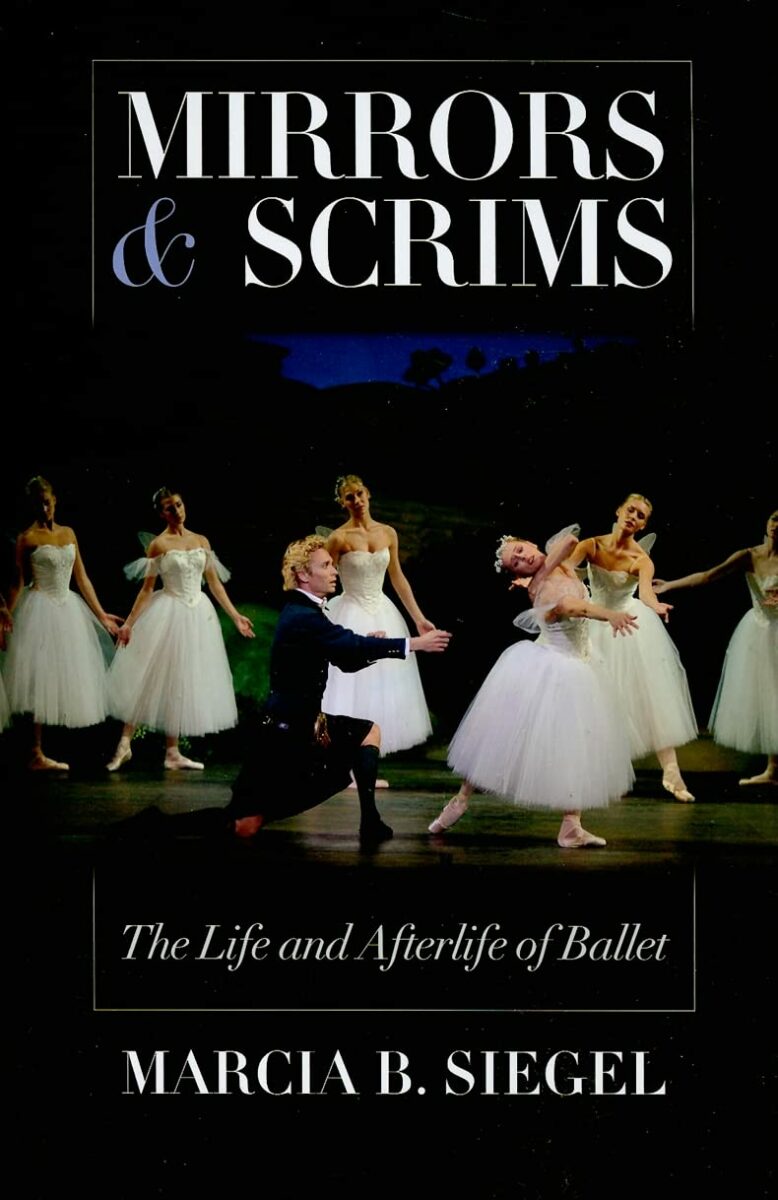

I wondered whether there was media manipulation involved on the part of the companies and I turned to what is perhaps my favourite book of collected reviews—Mirrors and Scrims. The Life and Afterlife of Ballet, written by American dance writer and critic Marcia Siegel. Siegel remarks, ‘I see myself as both a demystifyer and a validator, sometimes an interpreter, but not a judge.’ Personally, I stand with Siegel’s concept of a critic being a ‘demystifier’, ‘validator’ and ‘interpreter’ and I make an effort to avoid being judgmental. But I’m not sure that is how those who suggest that I not write about their productions think about reviews. To make the matter even more frustrating, it seems that eventually the Canberra-based organisation relented and gave permission for two other Canberra-based critics to review the show. But the permission was not passed on to me.

Whatever the reasons behind the issue, I am exasperated by the situation. I don’t tell those involved with putting a show together what steps to put in their choreography so why should they tell me what I can or can’t write? An honest review may well contain some criticism. But good reviews have to be honest and there will always be cases where a reviewer will feel the need to suggest there are issues that cause a work to fall short. Such criticism is not meant to be judgmental, but to be of potential benefit both for readers and for those who produce and perform in the shows. Reviews matter. They stand strong against flowery media releases, and they also help to create a history of what is regarded by many as an art form that disappears when a performance finishes. Admittedly twice is not a huge number of times for the situation to have occurred, but it represents a significant movement for the future perhaps?

Dance in Canberra, local dance that is, is largely made for a variety of community groups with the major exception being Alison Plevey’s currently-funded Australian Dance Party. Those community groups are made up of people of a certain age, people from a variety of multicultural backgrounds, people with medical conditions that benefit from access to movement, and a variety of other specific groups. Many community performances by these groups are exceptional and are often, even usually, danced outside the environment of a regular theatre, giving audiences a new perspective on where dance can happen. But in order to see professional productions from Australia’s major companies who rarely bring their work to Canberra, I travel a lot outside the city where I live.

The show that stood out for me during 2024 was Coco Chanel. The life of a fashion icon choreographed by Annabelle Lopez Ochoa and performed in Brisbane by Queensland Ballet,

The work was quite episodic, which is hardly surprising given the extent and changing nature of Chanel’s career. But Lopez Ochoa handled this episodic context with absolute skill. There was never any doubt about what was happening, despite the complexity, and the short duration of each episode. Choreographically her use of the space of the stage was carefully considered as were the groupings she made between dancers as the episodes unfolded. In addition, the collaborative elements, especially Jon Buswell’s lighting design, made Coco Chanel an absolutely brilliant production.

The aspect I especially loved was Lopez Ochoa’s approach to her choreography. It was distinctively individualistic, but emboldened by an understanding of, and belief in, classical ballet as a medium to be pursued. It has been a long time since I sat in a theatre and was completely and utterly absorbed to the extent that somehow I felt I was part of the story.’

MIchelle Potter, 25 January 2025

Featured image: Luke Dimattina (foreground) as Pierre Wertheimer in Coco Chanel. The life of a fashion icon. Queensland Ballet, 2024. Photo: © David Kelly.