Firestarter, documenting the origins and rise of Bangarra Dance Theatre, is filled with emotion—from joy to sadness and everything in between. But leaving the emotions to one side for the moment, I was utterly transfixed by two political moments that were part of the unfolding story. The first was footage of former Prime Minister Paul Keating giving his famous ‘Redfern Speech’ in 1992. In that speech Keating gave his assessment of Aboriginal history as it unfolded following the arrival in Australia of the British in the 18th century. ‘We committed the murders,’ he said. ‘We took the lands.’ ‘We brought the diseases.’ ‘We took the children.’ The second was by another former Prime Minister, John Howard, explaining in 1998 why, in his opinion, there was no need to issue an apology to the Indigenous population of Australia for wrongs committed to those people. Such disparate points of view. How sad is that and how can that be?

As mind-blowing as it was seeing those two political moments unfold, however, Firestarter was certainly more than politics. It traced the story of three brothers, Stephen, David and Russell Page from their childhood in Brisbane to their training at what became the National Aboriginal and Islander Skills Development Association, NAISDA; their roles in the establishment and ongoing development of Bangarra; and the frightening end to the lives of David and Russell. Along the way we met others involved in the complex story—Carole Johnson, founder of NAISDA and Bangarra; Frances Rings, currently associate artistic director of Bangarra; cultural consultants Djakapurra Munyarryun and Elma Kris; several current and past dancers of Bangarra; Wesley Enoch, artistic director across a range of theatrical organisations; Hetti Perkins, daughter of Aboriginal activist Charles Perkins; Hunter Page Lochard, son of Stephen Page; Rhimi Page, son of Russell Page; and others. All had unique stories and points of view.

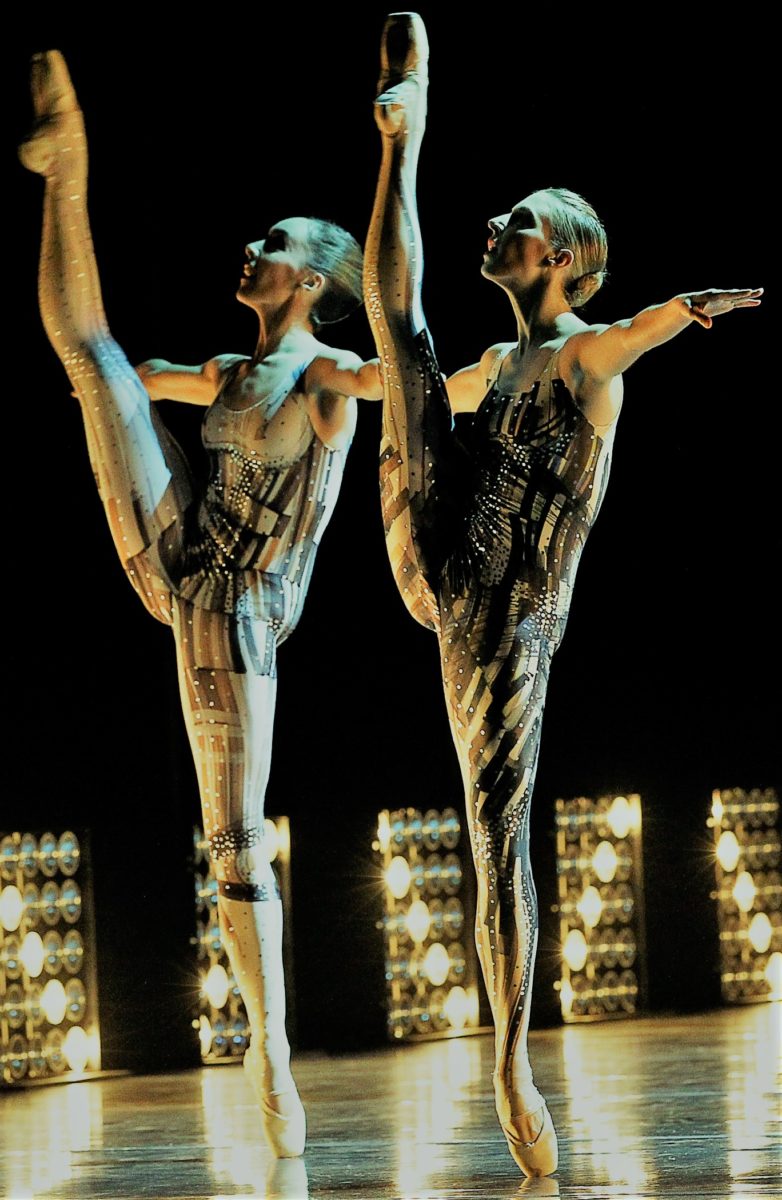

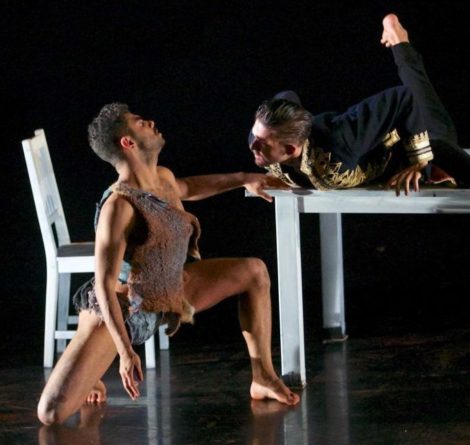

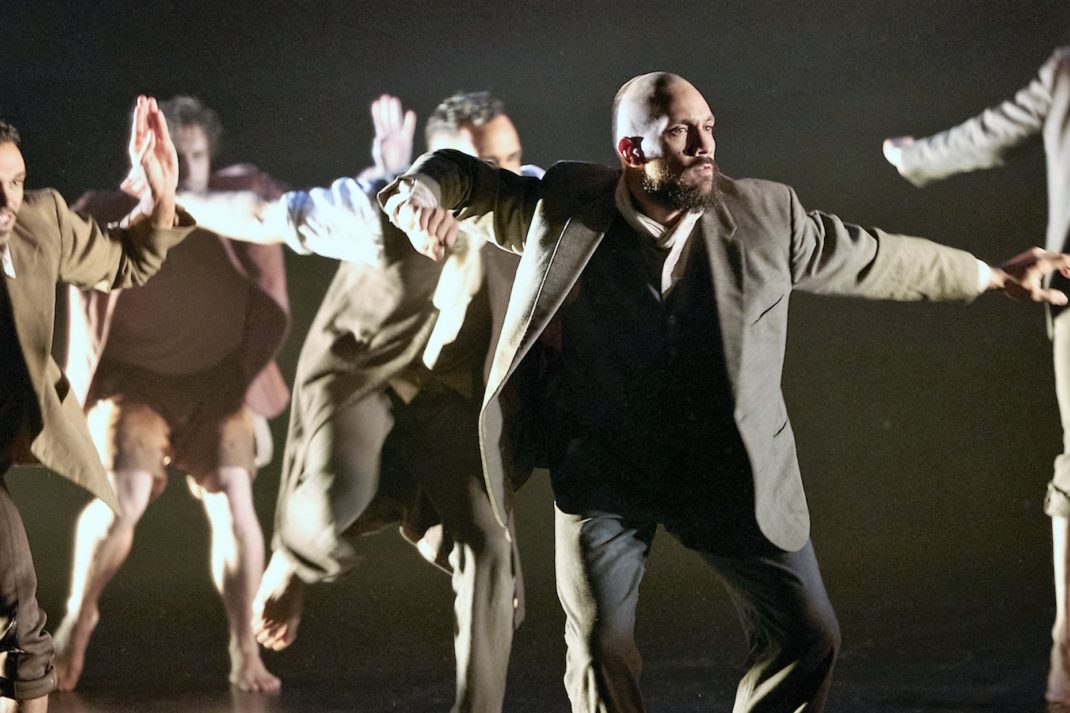

There was of course some great dancing from Bangarra performances over the 30+ years of its existence, and there was some gorgeous footage of a young David (as Little Davey Page) singing on early television shows such as Countdown and the Paul Hogan Show, along with scenes from his theatre shows. Then there was compelling footage from the Indigenous component of the opening ceremony for the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games. But perhaps most moving of all were scenes from Bennelong, Bangarra’s ground breaking work from 2017, which was described in the film as Stephen Page’s most successful work to date, and which he made as he worked at recovering from the death of his brother David in 2016.

Also associated with the death of David Page was footage from the presentation to Stephen of the prestigious J. C. Williamson Award at the Helpmann Awards event in 2016. The acceptance speech Stephen made (supported by his son Hunter standing beside him) so soon after the death of David was gut wrenching to watch and hear.

But on a more joyous note, perhaps my favourite part of the whole film was watching Stephen, the proud grandfather, holding his baby granddaughter, daughter of Hunter and his wife. Life continues. Life triumphs. Bangarra, such an exceptional company, moves forward.

This beautiful and challenging film was directed by Wayne Blair and Nel Minchin and produced by Ivan O’Mahoney.

Michelle Potter, 2 March 2021