20-30 November 2019. Te Whaea Theatre, Wellington

reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

NZSD’s Graduation season always displays the talent and enthusiasm of graduating dancers who, after three years’ training, are poised to venture forth and seek ways to make a professional career. Commitment and courage are needed in equal measure. Selected first and second year students are included in the casting, which is credit to them and their tutors since no dancer is less than fully prepared and present.

This year’s season combines classical ballet and contemporary dance works, eight in all, on the same program. (Last year’s had alternate nights for classical and contemporary works). Either formula offers the chance for us to consider how the two dance lineages as taught in the School, contrast with, or relate to, each other in the professional dance world—in technique, movement vocabulary, choreographic themes, aesthetic choices, relationship to music.

While many aspects of each are distinct, dances labelled ‘classical’ or ‘contemporary’ are not the opposites of each other. My take is that it’s the individual choreographer who places a work where it lies on the spectrum. If it’s good, then dance is the winner on the night. Memories of a masterpiece by Jiří Kylián in a recent Grad. program combined performers from both streams of training and demonstrated that truth (as also did a recent film viewing of Douglas Wright’s masterpiece from Royal New Zealand Ballet repertoire, rose and fell—truly superb contemporary choreography being performed by ballet dancers. QED.)

O body swayed to music, o brightening glance,

how can we know the dancer from the dance?

William Butler Yeats

The performance opens with Concerto Barocco by George Balanchine, to the Double Violin concerto by Bach. The clarity of music is matched in dance line, alignment and groupings. It is luminous, timeless, time less, time more.

My verses cannot comment

on your immortal moment or tell you what you mean;

only Balanchine

has the razor edge and knows that art of language

Robert Lowell

Velociraptor, by Scott Ewen, to music by Kangding Ray, is a premiere. The opening section is swift and driven. Among the cast of nine, we notice a wrist bandage on one dancer. Have the rehearsals come at a cost? We notice another. Soon the bandages unravel and become strings that tie and bind, forming mesmerizing tensions between groupings, and becoming cats’ cradles for bodies lifted horizontally.

Mind is music…

Invisible dancer who dances quicksilver vision

James Schevill

Not Odd Human, by Sam Coren, to music by Richard Lester, recently premiered at Tempo Dance Festival. It’s a manic mediaeval mayhem, its sardonic humour propelling characters from long ago and faraway into our midst. Mad Joan and Dull Grethe are there, Joan of Arc, Lady Godiva perhaps? You could credit Breugel with its design.

Such rollicking measures, prance as they dance

In Breugel’s great picture, the Kermess.

William Carlos Williams

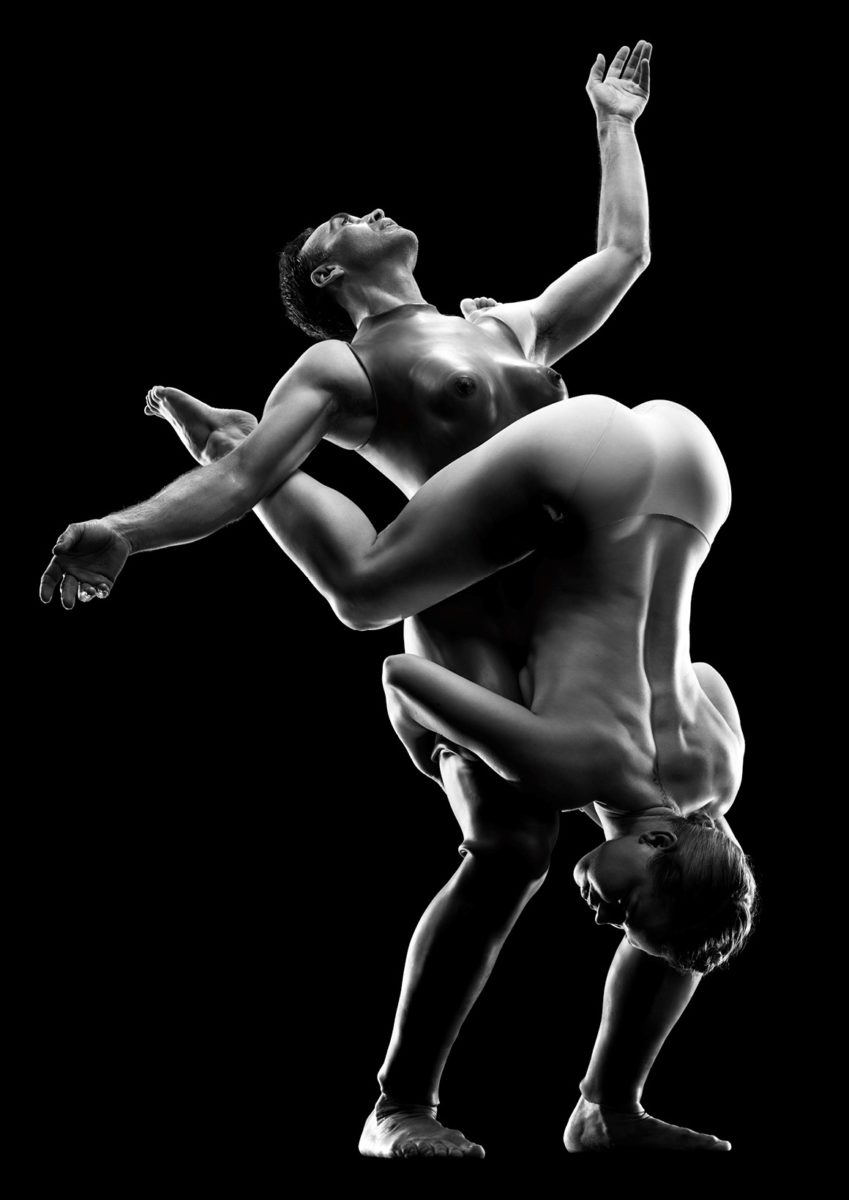

Five Variations on a Theme, by David Fernandez, to a Bach Violin Concerto, is a solo danced by Rench Soriano. Everything about this phenomenally gifted dancer, a second year student, combines precision with poetry, and is a joy to witness. His dancing is redolent of his tutor Qi Huan, who has rehearsed him in this work. For many years Huan was the leading dancer in Royal New Zealand Ballet, where his peerless command of technique gave him the expressive freedom that dance at its soaring best can offer. Before him, Ou Lu, before him Martin James, before him Jon Trimmer, before him Poul Gnatt. Soriano is clearly profiting from his teacher and this pedigree heritage, and will make a fine career for himself.

The dancer dances. The dance does not dance…

The saved world dances, and the dance dances.

Jacques Audiberti

Re:Structure, by Ross McCormack, to music by Jason Wright, was another premiere work. A 5 metre long pole is the central prop around which the cast of 8 dancers manipulate and explore its positioning. One dancer vertically atop the pole makes a striking image to which you could supply your own narrative, but there is deliberately no denouement to the work overall.

Your props had always been important:…

Things without a name you fell upon

Or through …

Richard Howard

Round of Angels, by Gerald Arpino, from 1983, to music of Mahler, has a cast of six males, then joined by a single female. As a couple, Brittany-Jayde Duwner and Jordan Lennon dance with secure command and lyrical expression, becoming the central tender core of the work.

I said that she had danced heart’s truth

W.B Yeats

Handel—A Celebration by Helgi Tomasson, to excerpts by Handel, has a large cast of spirited movers who rise to the spirit of the celebratory music. Rehearsed by Christine Gunn and Nadine Tyson, the staging had enthusiasm and style in equal and full measure.

Dancer: O you translation

Of all transiency into action, how you made it clear!

And the whirl of the finish, that tree of motion,

Didn’t it wholly take in the hard-won year

Rainer Maria Rilke

Carnival.4, by Raewyn Hill, was anything but carnivalesque in its mood. Its effect was percussive, tight, driven, insistent, urgent, pulsing. It evoked youth in support of each other, demanding to be listened to.

What is the hardest task of Art?

To clear the ground and make a start …

To tell the tale…

That when the millions want the few

Those can make Heaven here and do.

John Masefield

Nothing about dancing is easy—it’s just meant to look that way, and the quality of sprezzatura, nonchalance, while delivering virtuosic choreography is the one you’d aspire to. The most outstanding dancer of the evening is for me the personification of that gift of grace, and will surely make the world a better place wherever he dances. We all need to consider and study that quality, and pray for a bit of it in our lives, dancing and all the rest.

Come to the edge.

We might fall.

Come to the edge.

It’s too high!

Come to the edge.

And they came,

and he pushed,

And they flew.

Christopher Logue

Jennifer Shennan, 22 November 2019

Featured image: Rench Soriano in Five Variations on a Theme. New Zealand School of Dance, 2019. Photo © Stephen A’Court