Last week I interviewed designer Hugh Colman for the National Library of Australia’s oral history program. Colman is currently working on designs for the Australian Ballet’s new production of Swan Lake, due to open in Melbourne in September and, while Swan Lake did enter into the conversation, Colman was appropriately discreet on the recording about those aspects of the production, including his designs, which are not yet public property. But the discussion that did develop set my mind racing.

In 2004 I was invited to write a program note for the second season of Graeme Murphy’s Swan Lake. The brief was that it was not to be so much about the Murphy production but about the popular appeal of the ballet. I loved writing this piece. I called it ‘Do you know Swan Lake?’ after the question, with its suggestion of what to do if the answer was yes, that was occasionally bandied around in schoolyards several decades ago, and that my father also loved to use to tease his daughter.

If I were writing the program piece now I would probably use other examples of how Swan Lake has permeated the popular imagination. There is a recent episode of that English detective series for television Midsomer Murders, for example, which is loosely based on Swan Lake. It features a (fictitious) former Russian ballerina preparing ballet students for a concert in a local church hall. And what are the students rehearsing? Why ‘Dance of the Little Swans’ of course. And the story reaches its high point when the former ballerina is rescued in the nick of time from following in the footsteps of Odette and being drowned in Swansdown Lake by the ‘perp’, as culprits are called in these kinds of shows. Not exactly great drama, but nevertheless it works on the assumption that the general audience for television knows Swan Lake. Then of course there’s The Black Swan, the movie, not great drama either in my opinion, but it has spawned a large amount of web comment from so many, from dancers to psychiatrists and of course the general public.

The question of popular appeal has been brought to the fore once again, in Melbourne only at this stage, with Gideon Obarzanek’s latest work There’s definitely a prince involved reviewed elsewhere (with comments) on this site. Not everyone enjoyed the deconstructivist approach that Obarzanek took, but there’s no denying that There’s definitely a prince involved deals with that mysterious attraction that Swan Lake has over the public.

What is it about this ballet that continues to fascinate? And I continue to search in my mind for the production that most clearly captures the essence of the work for me. Perhaps that is yet to come, and perhaps that is what continues to fascinate.

Michelle Potter, 10 March 2012

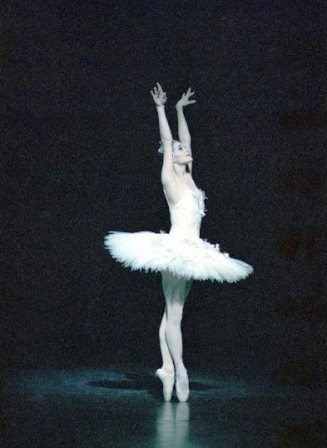

Here is the link to my 2004 program article. I have not been able to find contact details for the photographer, Michael Cook, whose photograph appears with the article. I would be pleased to hear from anyone with information that might assist.

Sometimes I think it’s simply laziness that results in “Swan Lake” being pressed into service for ballet requirements in popular entertainments. Like the once ubiquitous “O Fortuna” from “Carmina Burana”, “Dies Irae” from Verdi’s Requiem and the “Ode to Joy” from Beethoven’s Ninth which used to be mainstays in television adverts trying to goose up the appeal of something, Swan Lake produces instant brand recognition, especially the Little Cygnets dance.

Was it during the 1930’s that “Swan Lake” began it’s rise to the forefront of peoples’ imaginations as being the quintessential ballet ? Was it something about the perceived spirirtuality surrounding it and “Les Sylphides” that resulted in their both giving solace during that fraught decade. Certainly judging by the sheer volume of photographs and “artistic” representations made during this period those two ballets had the most impact on the popular imagination. Interestingly, the corps costumes in the de Basil Swan Lake Act 2 were basically the longer Romantic bell shaped ones used in Les Sylphides, so both ballets have something of the same feeling in photographs.

A new traditional production is always exciting to contemplate. So many issues to deal with : which version of the score to use as the basic template [1877 or 1895], do we include the Act 1 pas de trois, what to do about the Act 3 national dances, do we give Siegfried a dreamy solo somewhere, do we add some music to the very short Act 4, etc, etc.

We have been fortunate, I feel, with the so called traditional productions of “Swan Lake” [Anne Woolliams] and “Sleeping Beauty” [Maina Gielgud] staged in the past by the AB. I am certainly looking forward to the new “Swan Lake” coming this year, especially as we have a great crop of prospective leads.

John Wiley has written that Swan Lake, in its interpretations post Petipa and Ivanov, is the balletic counterpart of Macbeth or Hamlet: interpretations depend on ‘the concerns and world-view of the interpreter’. I have always been interested too in Arlene Croce’s essay “Swan Lake” and its alternatives, which appears in the collection Going to the Dance. She writes that she keeps going to see Swan Lake ‘not to resee a ballet but hoping to see the ballet beyond the ballet’ and the essay grows out of her curiosity (via Wiley’s work) about Tchaikovsky’s score and her feeling that the music is suggesting more than what is happening on stage.

You are right that early productions used the long romantic style tutu (except for Odette of course) and in attempting to identify old photographs I have often looked for wings to confirm that an image of a corps of women clad in long white dresses is from Sylphides and not Swan Lake. The other interesting thing about early productions is the appearance of Benno in Act II, which both Wiley and Croce mention. Benno was a fixture in early Australian productions by visiting companies and the Borovansky Ballet and I recall being puzzled when I first saw a version without him – was it the Australian Ballet’s first full-length production perhaps? The image below (a detail) shows Ann Somers (Kathleen Gorman) and Miro Zloch as Odette and Siegfried with Rex Reid as Benno during the Ballet Rambert tour to Australia 1947-1949.

I agree that we have been fortunate with the traditional productions staged by the Australian Ballet. I continue to admire the Anne Woolliams production, largely for its inherent dramatic logic. But Stephen Baynes and Hugh Colman have had the luxury of an extended research and development period and I hear that Baynes is well and truly into the choreography. So it is something to anticipate.

Photo credit: Walter Stringer, National Library of Australia