- Michelle Ryan

In February I had the pleasure and privilege of recording an oral history interview with Michelle Ryan for the National Library’s Oral History and Folklore Collection. Ryan is currently artistic director of the Adelaide-based Restless Dance Theatre.

Canberra audiences may remember Ryan as a member of the Meryl Tankard Company. She joined in 1992 so was only seen during the last year of the company’s four year stint in Canberra. When the company moved to Adelaide in 1993, becoming Meryl Tankard Australian Dance Theatre, Ryan went with them. She danced in all the works Tankard staged in Adelaide and was an especially wonderful tap-dancing fairy in Aurora. In the interview she explains that tap had been one of her childhood specialties when she was learning to dance at the Croft Gilchrist School of Dancing in her home town of Townsville.

Ryan’s story, including her struggle with the ravages of multiple sclerosis, is an amazingly courageous one and is told with honesty and integrity. She has not placed restrictions on the interview and it will be available as online audio over the National Library’s website in due course. [Update: Here is the link to the online audio]

- Stella Motion Pictures

In February I also caught up with Melbourne-based film maker Philippe Charluet who has been in Canberra working on a project called The Heritage Collection. Charluet filmed most of Graeme Murphy’s productions during Murphy’s artistic directorship of Sydney Dance Company and The Heritage Collection will showcase excerpts from many of those shows. It is still in its early stages but what a nostalgic look back it gives already. And oh the beautiful Katie Ripley in the Grand promo (to choose just one artist).

- Press for February

‘Staging unique challenge’. Review of A Tale of Two Cities, The Canberra Times, 7 February 2014, p. Arts 6. [Online version no longer available]

Michelle Potter, 28 February 2014

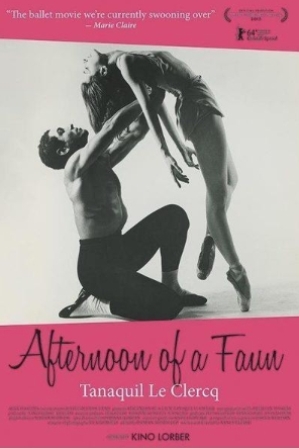

Tanaquil LeClercq

A documentary on one of New York City Ballet’s most luminous dancers, Tanaquil LeClercq, was shown last year at the New York Film Festival and is at the moment being shown at festivals in Germany, notably Berlin. Called Afternoon of a Faun: Tanaquil Le Clercq and made by Nancy Buirski, it has just been released commercially.

The trailer gives a tiny glimpse of what we might expect on this documentary, which is about 1½ hours long. There is some footage of LeClercq, partnered by Jacques D’Amboise in the Robbins Afternoon of a Faun, which indicates what an extraordinary interpretation these two gave to the role. But there is much else to admire, even from the trailer. What a fabulous performance in the very brief look we get at Western Symphony! and so on … The still photographs are just incredible too.

I can’t wait to see the full documentary despite the fact that some critics have suggested it is ‘flawed’ in parts. The footage is archival of course and so, sadly, a little blurred but even with the lack of high definition LeClercq is staggering.

Michelle Potter, 16 February 2014.

Rafael Bonachela and Interplay

In January I talked to Rafael Bonachela, largely about his new triple bill program, Interplay, which will open in Sydney in March and then travel to Canberra in April and onwards from there. Interplay features brand new works from Bonachela and Gideon Obarzanek and a return to Australia of Jacopo Godani’s Raw Models.

Rafael Bonachela at Walsh Bay. Photo: Rafael Bonachela at Walsh Bay. Photo: © Peter Grieg It is hard to think of anyone who has such enthusiasm and passion for dance, or anyone who loves talking so generously about what he is doing. The story has just been posted on DanceTabs. Here is the link.

INTERPLAY

Choreography by Rafael Bonachela, Gideon Obarzanek and Jacopo GodaniSYDNEY: 15 March – 5 April, Sydney Theatre

CANBERRA: 10–12 April, Canberra Theatre Centre

MELBOURNE: 30 April – 10 May, Southbank TheatreMichelle Potter, 4 February 2014

Dance diary. January 2014

- Graduation Ball

In January I received a query via the contact box on this site about some YouTube footage of Graduation Ball. I had never come across this footage before and sadly the vision is of very poor quality. The material has obviously been transferred from format to format on more than one occasion. As for the query, it concerned the date of the footage and eventually I suggested the date of 1947–1949 from the late period of de Basil’s company in the United States. What made me initially feel that it was late 1940s was that I thought I saw, for a flash, Valrene Tweedie as one of the ‘fouetté girls’. In one of the interviews I did with Tweedie I asked her about the roles she had danced in Graduation Ball and she mentioned that she had been one of the ‘fouetté girls’ for de Basil towards the end of her career with him. Watching the footage, I thought I caught a glimpse of a familiar facial expression. Peering hard at the opening credits, I noticed the name Paul Grinwis, and further investigation confirmed that Grinwis had been with de Basil in the late 1940s, which confirmed my initial dating.

Below are links to the two segments of footage. Any further information would be most welcome

- P

Further information about some of the images in the National Library’s Bodenwieser collection has recently come to light. Those close to Bodenwieser recently identified the ‘unknown dancers’ in some of the Library’s digitised images. The most interesting comments concern a photograph of dancers on what has been regarded as a 1950s New Zealand tour. Well this is probably not the case.

The dancers in the image above have been identified as L—R back row: Jean Raymond, Madame Bodenwieser, Pamela Mossman, Dory Stern; L—R front row: Elaine Vallance, Coralie Hinkley, Mardi Watchorn, Eileen Cramer, Denise Searlie. Those who appeared with Bodenwieser around this time say that neither Pamela Mossman nor Denise Searlie performed in New Zealand and that their time with the company was earlier than the date of 1950 given on the record. They believe that the photograph was taken around June 1948 (the weather is cool as suggested by their clothing) and at that time the Bodenwieser Ballet performed in Brisbane and on the north coast of NSW. They suspect the photograph was shot at Brisbane Railway Station. The National Library catalogue record should reflect this new information shortly. [Update September 2020: Sadly, this new information has not been added to the National Library’s catalogue]

- Coming soon

My recent interview with Rafael Bonachela is due to be posted soon on the DanceTabs website. I spoke to Bonachela in mid-January and, as ever, was overwhelmed by the passion and generosity of Sydney Dance Company’s current artistic director. A link to the post is forthcoming. [Update: here is the link].

Michelle Potter, 31 January 2014

Featured image: Rafael Bonachela at Walsh Bay, c. 2014. Photo: © Peter Grieg

Forklift. Kage

18 January 2014 (matinee), Carriageworks, Eveleigh (Sydney). Sydney Festival 2014

‘More than dance’ the advertising says. And it is indeed difficult to categorise Forklift by Melbourne-based company Kage with anything more specific than that. A work for three performers and a forklift vehicle, it highlights in many respects the tension between the fragility and delicacy of the human body and the solidity and strength of a robust piece of machinery.

Rehearsal for Forklift But then does it? The performers, Henna Kaikul, Amy Macpherson and Nicci Wilks, are extraordinary. They had me with my heart in my mouth as two of them moved from one impossible pose to another, balancing, dangling and wrapping themselves around the forklift, changing places every so often with the third performer who drove the vehicle. The skills they exhibited (apart from being able to drive a forklift) ranged from straight circus stunts to acrobatic tricks and occasionally what might be called powerful, perhaps outrageous contemporary dance movement. Each performer often seemed as robust as the machine and it was only that we knew they were human beings that the tension gathered strength and settled inside us as audience members. That kind of emotional tension, rather than the more obvious man versus machine element, was perhaps the strength of Forklift.

I liked the tongue in cheek moments sprinkled throughout the show. Occasionally, whichever performer was driving the forklift would sit back in the cabin with one foot resting on the dashboard, pick up a magazine and nonchalantly start reading as she transported the other two performers, who were on the roof, or the forks, on wooden pallets being lifted upwards, or some other impossible place on the forklift, round the space of Bay 17 at Carriageworks. Then I liked the surreptitious stealing of potato crisps that went on shortly after the opening as two performers, who seemed like anonymous bodies at that stage, crept up behind a startled forklift driver and slowly dipped a hand into her just-bought snack. These moments added a light-hearted element to the piece.

There were one or two aspects of the show that I thought didn’t work so well. I’m not sure there was any sense of coherence pulling together the diverse elements of the piece. The slight narrative line centring on the experiences of a forklift driver as she goes about her business didn’t gel all that well with the more abstract elements of bodies versus machine, or with the straight circus tricks that popped up now and then. Having said that Nicci Wilks’ act with a huge and very heavy hula hoop was spectacular as a demonstration of technique.

Forklift was directed by Kate Denborough whose audacity when it comes to making ‘more than dance’ is becoming clearer with each work she creates. It had a commissioned score by Jethro Woodward, which to my ear sounded suitably industrial and yet at times was slightly mysterious as if we were looking into a world beyond the usual.

Michelle Potter, 19 January 2014

Featured image: Promotional shot for Forklift