This post contains two reviews of the 2023 Don Quixote. The first and longer one is of the digital screening; the second, shorter one refers, with particular reference to one dancer, to a matinee performance I saw in Sydney towards the end of the season.

Digital screening, March 2023. (Filmed live on 24 March 2023, Arts Centre, Melbourne)

This production of Don Quixote is meant to pay homage to the 1973 Australian Ballet film of the work and, in fact, has been spoken of as being ‘transposed from screen to stage’, especially with regard to the set. The early film production was choreographed by Rudolf Nureyev and was directed by Nureyev in conjunction with Robert Helpmann. Helpmann played the role of the Don, Nureyev was Basilio and Lucette Aldous danced Kitri/Dulcinea. To tell the truth I’m not sure why the ‘screen to stage’ comment was necessary as the ballet stands by itself without any pretence that it is a transposition. The 1970s film is, however, worth watching, especially now that it has been restored and remastered in high definition. It contains some exceptional performances, especially from Lucette Aldous whose performance in my opinion outshines that of Nureyev.

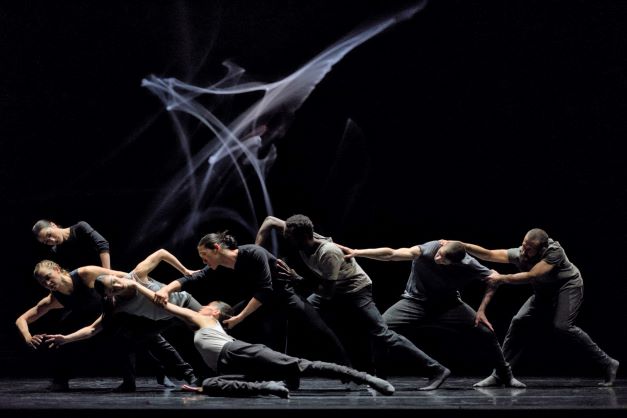

But to the production of 2023. I found this staging beautifully paced and full of action from every performer. Ako Kondo and Chengwu Guo as the leading characters were just brilliant, both technically and in terms of the emotional and dramatic relationship they built up between them. They also dance so well as partners with bodies and limbs moving smoothly together and with complementary line through the two bodies always obvious. Then there were those amazing moments when Guo lifted Kondo into the air and held her there with one hand (as seen in the featured image). The music paused momentarily for us to have a good look! Spectacular.

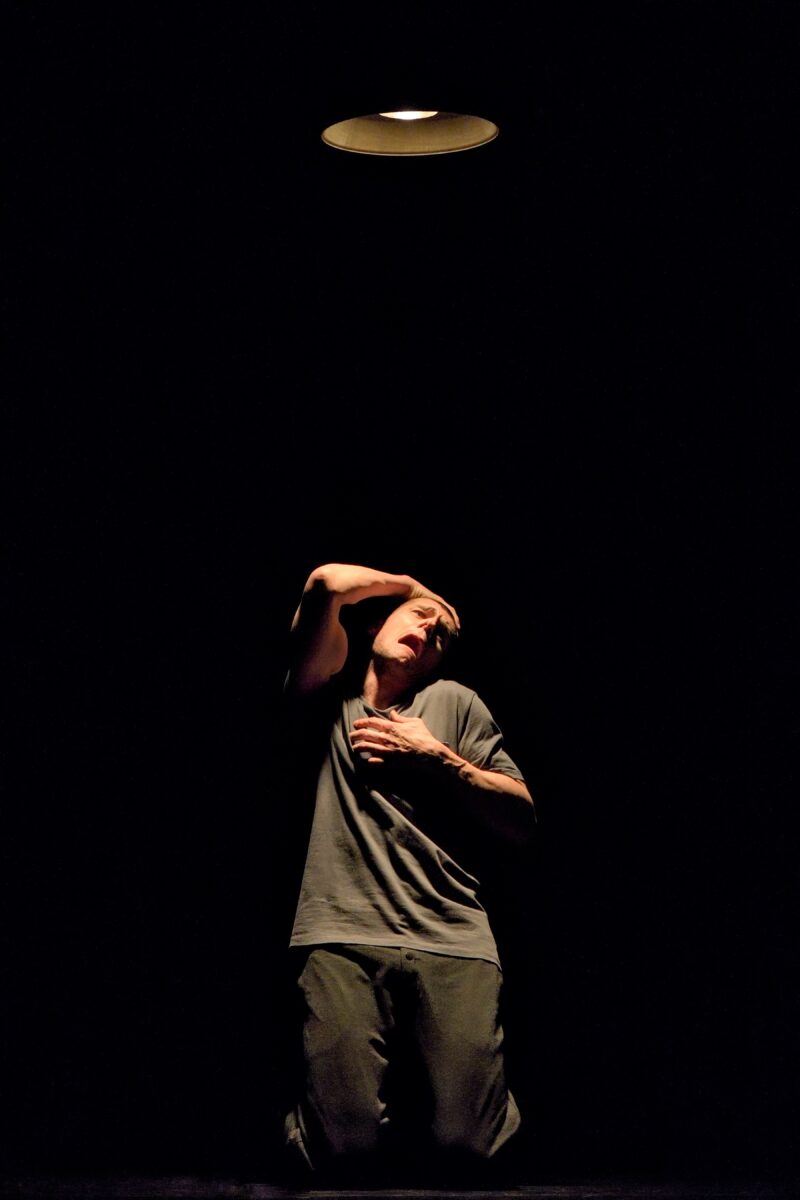

Adam Bull was an impressive Don Quixote. He had worked on a particular portrayal of the Don and maintained the behaviour of his character from beginning to end. He was eccentric but introspective and contemplative, and I got the feeling he was lost in another world, a world where windmills can be monsters and dreams can become reality in his mind. What I liked was that his character was strong but without any overplay.

Amy Harris as the Street Dancer performed nicely but I would have liked a little more colour in her characterisation. Sharni Spencer as the Queen of the Dryads managed her difficult variation skilfully and Yuumi Yamada was a charming Cupid. A highlight of the last act (apart from the grand pas de deux from Kondo and Guo) was an exciting Fandango danced by sixteen, magnificently dressed dancers led by Dana Stephensen and Nathan Brook.

Ludwig Minkus’ score was played by Orchestra Victoria conducted by Charles Barker, who was, I am assuming, visiting from New York. As with other conductors whom I admire, Barker ensured that the music and the dance worked beautifully as one. Then, as part of the curtain calls the dancers moved forward and, with a simple sweep of the arm, acknowledged the orchestra. It was a perfect, dancerly, elegant acknowledgement rather than the lengthy clapping by the dancers leaning towards, almost into, the pit that we have had to get used to over the past 20 years or so from the Australian Ballet.

The streaming also featured David Hallberg and Catherine Murphy discussing various aspects of the production with some segments featuring various artists associated with the production, including backstage staff.

Michelle Potter, 28 March 2023

22 April 2023 (matinee). Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House

Apart from the fact that there is ‘nothing like being there’ as the saying goes, most of my comments above from watching the streamed version of the Australian Ballet’s 2023 Don Quixote apply equally to the live performance I saw towards the end of the company’s Sydney season. The Australian Ballet is, in general, dancing beautifully, even stunningly at the moment. Apart from the technical standard being high, there seems to be an inherent joy emanating from the dancers. And what’s more I don’t feel the need to complain about the production looking squashed on the Sydney Opera House stage. For some reason (perhaps the joy mentioned above?), instead of looking squashed the production looked intimate. What a thrill!

But the highlight of the afternoon came from Yuumi Yamada dancing the leading female role of Kitri/Dulcinea. She isn’t a tall dancer, but then nor was Lucette Aldous in the Nureyev/Helpmann film made in 1972. As Kitri/Dulcinea Aldous gave Nureyev a run for his money. Yamada was, similarly, a deliciously feisty Kitri in Act I and was outstanding technically throughout. It was a performance that I feel privileged to have seen. Yamada was partnered by Brett Chynoweth as Basilio.

I also admired the dancing of Lilly Maskery as Cupid in Act II. She has a good presence onstage and gave the role a characterisation that attracted the eye, as well as dancing strongly. I look forward to seeing more of her work.

Unfortunately, I have no images of the cast from this matinee performance.

Michelle Potter, 25 April 2023

Featured image: Ako Kondo and Chengwu Guo in Don Quixote, ACT I. The Australian Ballet, 2023. Photo: © Rainee Lantry