Ever since the announcement that David Hallberg was to become the new artistic director of the Australian Ballet, there has been speculation about what he might bring to the company. With his extraordinary background across the world, including extended periods as a dancer with American Ballet Theatre in New York and Bolshoi Ballet in Moscow, as well as guest seasons with major companies around the world, including an extended position as principal guest artist with the Royal Ballet, it has seemed obvious that he would have much to offer. His contacts, and his wide personal experience, would ensure that he would be able to bring a diverse repertoire of works to the Australian Ballet. The announcement of the Australian Ballet’s season for 2021 shows exactly that.

The season is made up of a gala opening program in Melbourne, two mixed bill programs and three full-length works. Sound familiar? Looking more closely, however, the individual content of each season might be seen as somewhat unexpected. The opening season for Sydney dance goers is New York Dialects. It consists of two works by George Balanchine, Serenade and The Four Temperaments, which show somewhat different aspects of Balanchine’s output; and a newly commissioned work from Pam Tanowitz. Who could not look forward to Balanchine? But I am curious to see what Tanowitz produces as the one work of hers that I have seen (Solo for Russell for a New York City Ballet streaming program) left me cold I have to say.

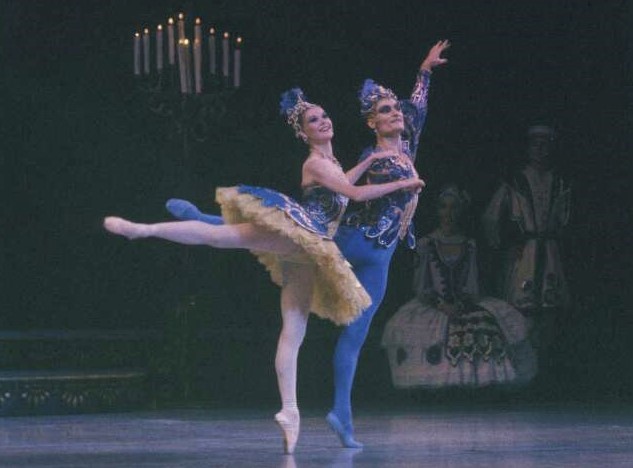

The other mixed bill has two vastly different works both based on the balletic vocabulary—Petipa’s third act from Raymonda and William Forsythe’s Artifact Suite. I had the pleasure once of seeing the full-length Artifact but have never seen the Suite that Forsythe created from the full-length version. I look forward to the Suite and I am sure it will contain all the startling aspects (blackouts, lowering of the front curtain in mid-performance, and so on) that characterise the full production. An interesting choice from Hallberg.

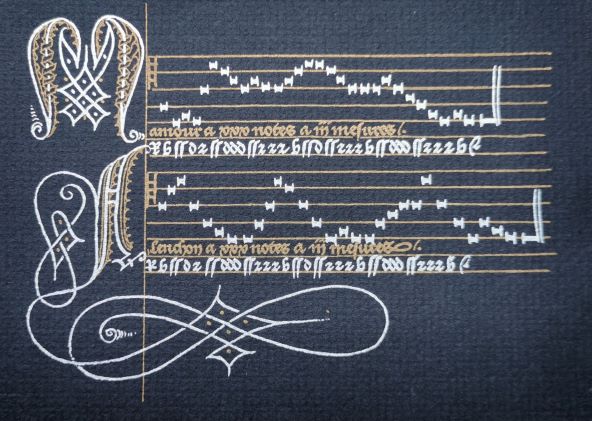

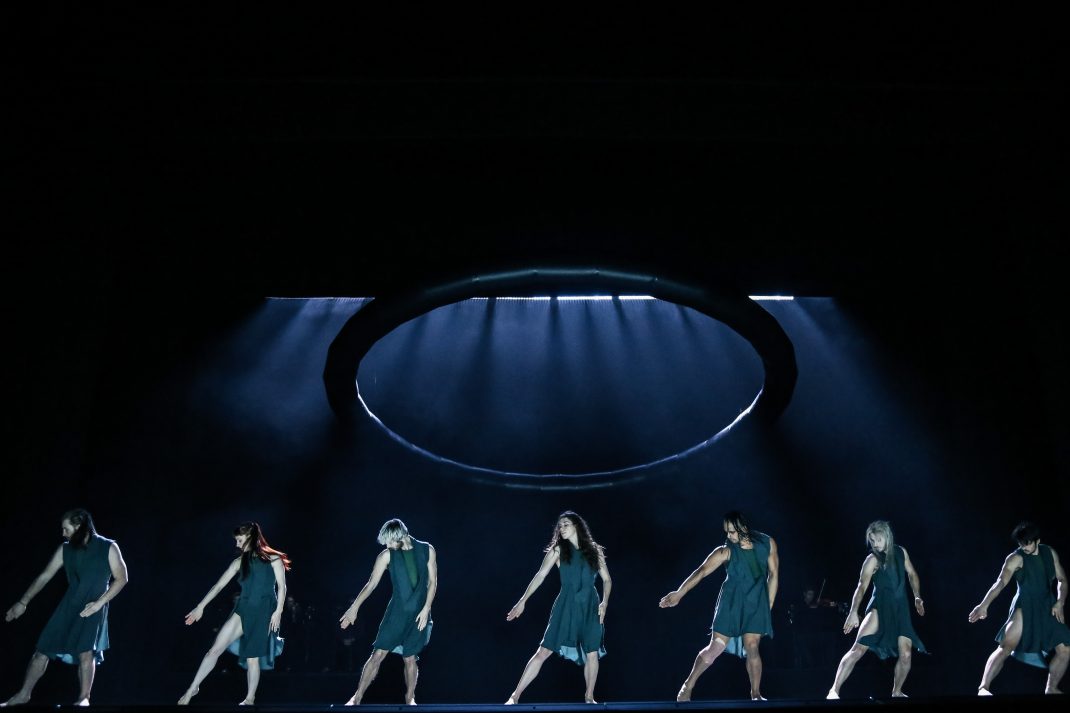

As for the full-length works, we will get to see (I hope, anyway) Anna Karenina with choreography by Yuri Possokhov, whose choreography I admire immensely; John Cranko’s familiar Romeo and Juliet; and Alexei Ratmansky’s revival of the long-lost Harlequinade, originally created by Petipa in 1900.

What has impressed me so far is the way Hallberg speaks about the repertoire for the 2021 season. His words are straightforward and clear but they don’t dumb things down at all. His discussion of the Counterpointe program, for example, he says

The juxtaposition of Raymonda and Artifact Suite shows the evolution of classical ballet. Raymonda adheres to tradition and pageantry; Forsythe took this history and ‘imitated’ it, creating a work that overwhelms both dancers and audience with gestural references given new meaning. These seminal works both counteract and perfectly complement each other.

It has also been interesting rereading his autobiography A body of work. Dancing to the edge and back (New York: Atria Paperback, 2017). Now he is the new artistic director, the sections in his book where he talks about seeking to understand more about the nature of ballet take on a new meaning. During the reread I especially admired his enquiring mind, and his interest in an analytical approach to certain aspects of his career.

Hallberg has good connections already with the Australian Ballet as a result of guesting with the company on various occasions, and from the extended time he spent in Melbourne being treated for injury by the company’s rehabilitation team. He is an exceptional dancer (oh those beats!) and I clearly recall the first time I saw him in 2010 in Kings of the Dance. ‘Hallberg danced with classical perfection,’ I wrote. But despite all the positive signs, he has to prove that he can direct a company successfully. A new era? Fingers crossed.

Michelle Potter, 31 December 2020

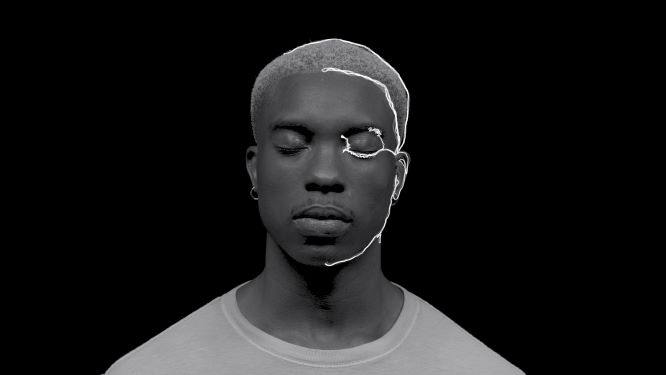

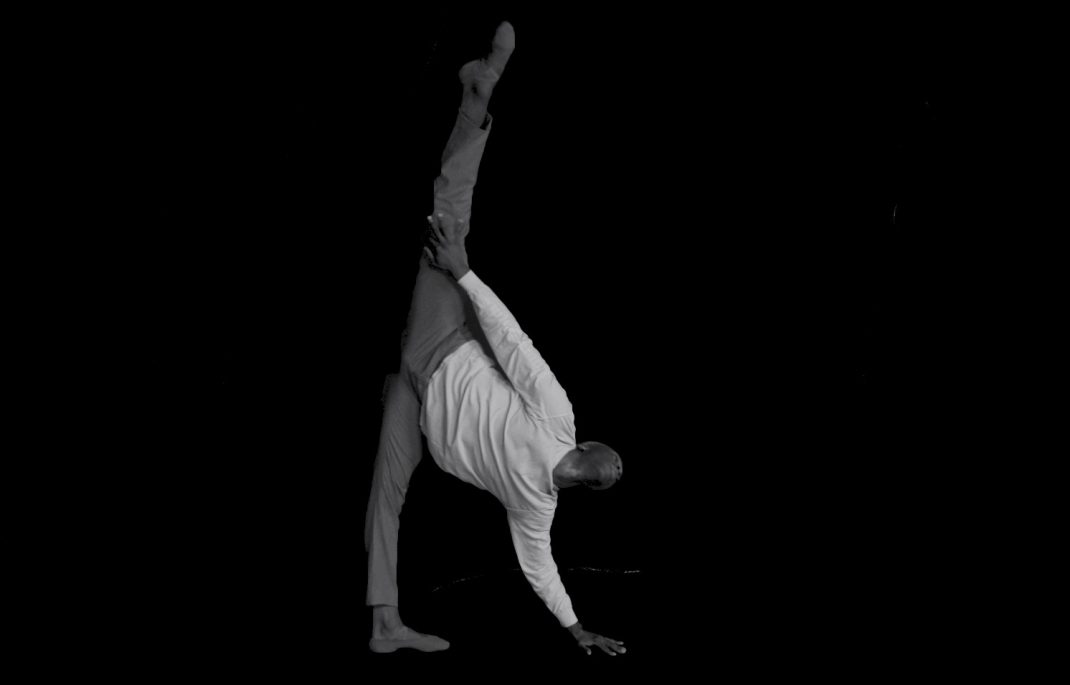

Featured Image: Brett Chynoweth in a study for Harlequinade. Photo: © Pierre Toussaint