This is an expanded version of an obituary written by Jennifer Shennan and published in The Dominion Post online on 2 April 2022.

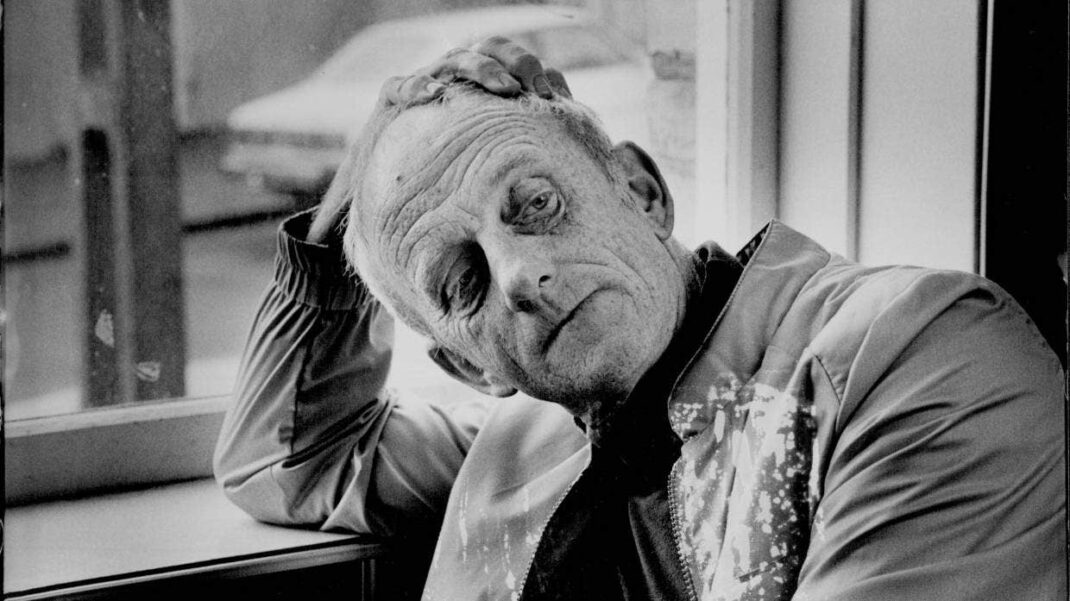

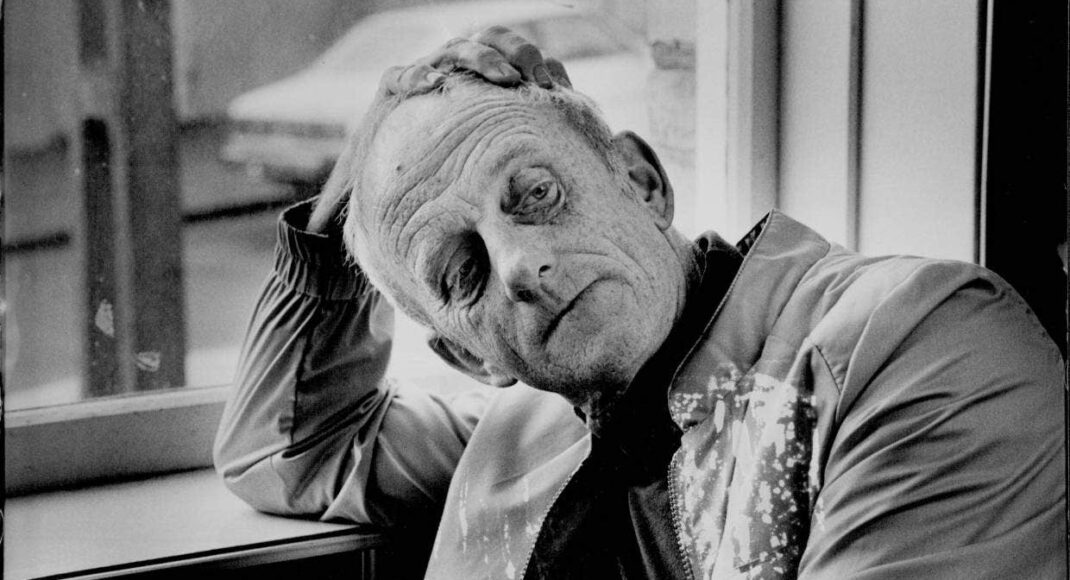

Russell Kerr, leading light of ballet in New Zealand, has died in Christchurch aged 92. The legendary dancer, teacher, choreographer and producer influenced generations of New Zealand dancers. Kerr’s hallmark talent was to absorb music so as to draw out character, narrative, human interest, emotion, poetry and comedy that ballet in the theatre can offer. Thrusting your leg high in the air, or even behind your head, just because you can, is the empty gesture of perfunctory performance that he found exasperating. Shouting and sneering at dancers, telling them they are not good enough, was anathema to him. One dancer commented, ‘Mr Kerr always treated you as an artist so you behaved like one.’

Born in Auckland in 1930, the younger of two sons, Russell was already learning piano from his mother, a qualified teacher, when a doctor recommended dance classes to strengthen against the rheumatoid arthritis that ailed the child. Did that doctor follow the remarkable career that ensued from his advice? Years later Russell was asked if it was difficult, back then, to be the only boy in a ballet school of girl pupils? He chuckled, ‘Oh no, it was marvellous—there I was in a room full of girls and no competition for their attention. It was great fun.’

Kerr made impressive progress both in dancing and piano, achieving LTCL level, then starting to teach. He could have been a musician, but dancing won out when in 1951 he was awarded a Government bursary to study abroad. In London he trained at Sadler’s Wells, with Stanislaw Idzikowski (a dancer in both Pavlova’s and Diaghilev’s companies), and also Spanish dance with Elsa Brunelleschi. Upon her advice and just for the experience, he went to an audition at the leading flamenco company of José Greco. Flamenco would be one of the world’s most demanding dance forms, both technically and musically. Remarkably, he was offered the job, providing he changed his name to Rubio Caro! How fitting that Kerr’s first contract was as a dancing musician. When asked later how he’d managed it he replied, ‘Oh, I just followed the others.’

After a time, Sadler’s Wells’ leading choreographer, Frederick Ashton, declared Russell’s body not suitably shaped for ballet. ‘I’ll show you’ he muttered to himself, and so he did. In a performance of Alice in Wonderland, he scored recognition in a review (‘Kerr’s performance as a snail was so lifelike you could almost see the slimy trail he left behind as he crossed the stage.’ As he later pointed out, ‘not many dancers are complimented in review for their slimy trails’). A sense of humour and irony was always hovering.

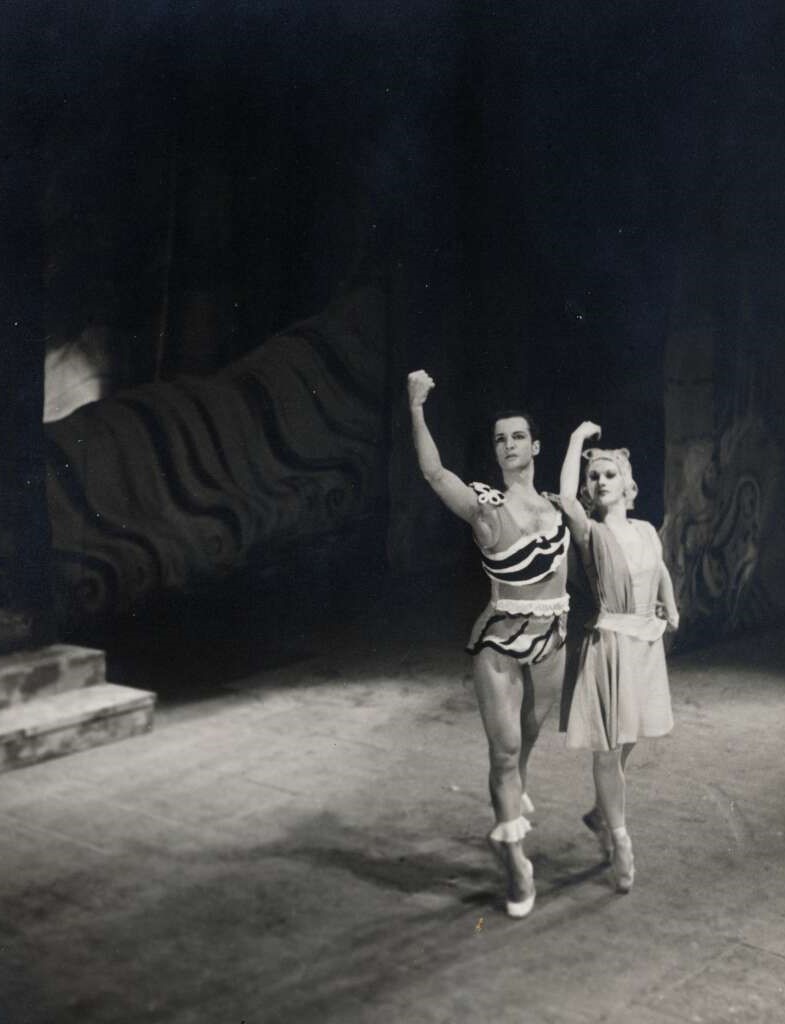

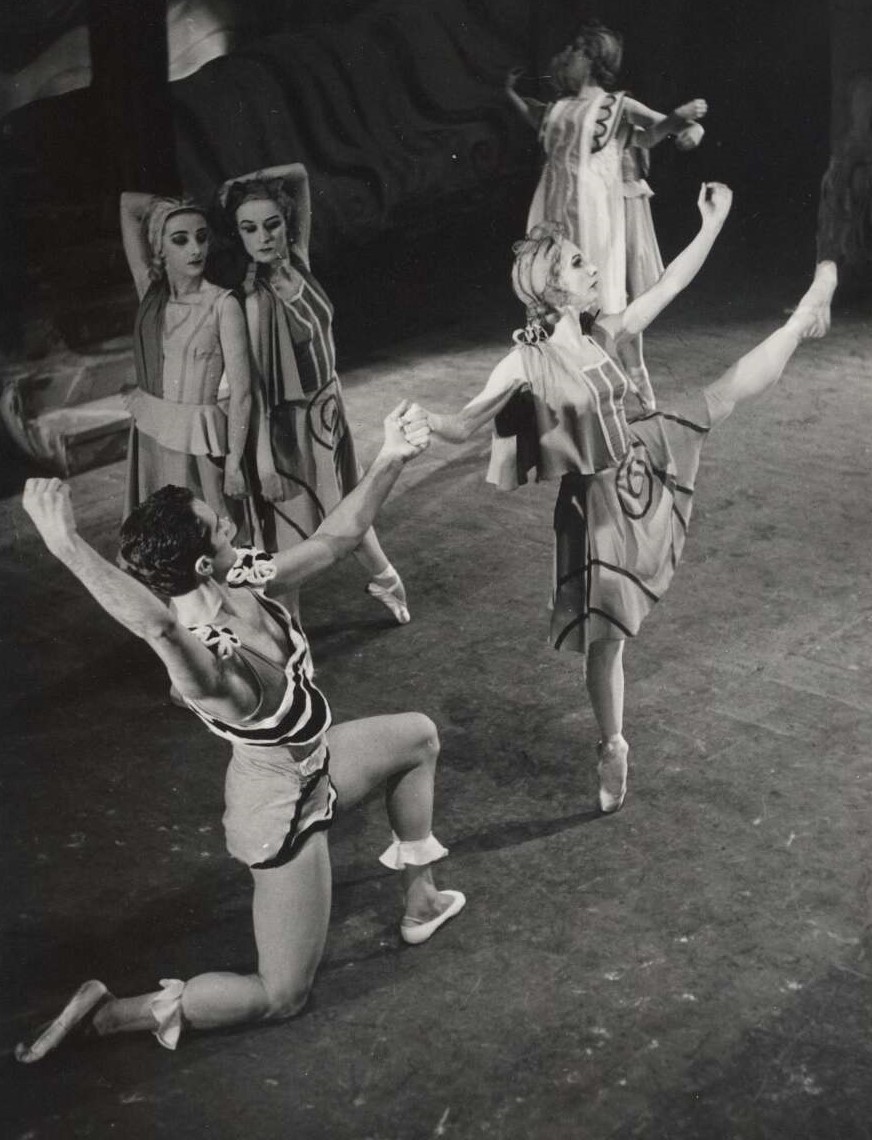

Kerr danced with Ballet Rambert, and was encouraged towards choreography by director Marie Rambert. Later he joined Festival Ballet, rising to the rank of soloist, earning recognition for his performances in Schéhérazade, Prince Igor, Coppélia, Petrouchka among others. Nicholas Beriosov had been regisseur to choreographer Fokine in the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. Kerr’s work with him at Festival Ballet lent a pedigree to his later productions from that repertoire as attuned and authentic as any in the world.

The investment of his Government bursary was exponentially repaid when Russell, now married to dancer June Greenhalgh, returned to New Zealand in 1957. He told me he spent the ship’s entire journey sitting in a deck chair planning how to establish a ballet company that might in time become a national one. Upon arrival he was astonished to learn that Poul Gnatt, formerly with Royal Danish Ballet, had already formed the New Zealand Ballet and, thanks to Community Arts Service and Friends of the Ballet since 1953, ‘…they were touring to places in my country I’d never even heard of. So I ditched my plans and Poul and I found a way to work together.’

Kerr became partner and later director of Nettleton-Edwards-Kerr school of ballet in Auckland. (I was an 11 year old pupil there. It was obvious that Mr Kerr was a fine teacher, encouraging aspiration though not competition. We became friends for life). Auckland Ballet Theatre had existed for some years but Kerr built up its size and reputation, staging over 30 productions. Perhaps the highlight of these was a season of Swan Lake on a stage on Western Springs lake. He produced a series, Background to Ballet, for Television New Zealand in its first year of broadcasting, and also choreographed many productions for Frank Poore’s Light Opera Company.

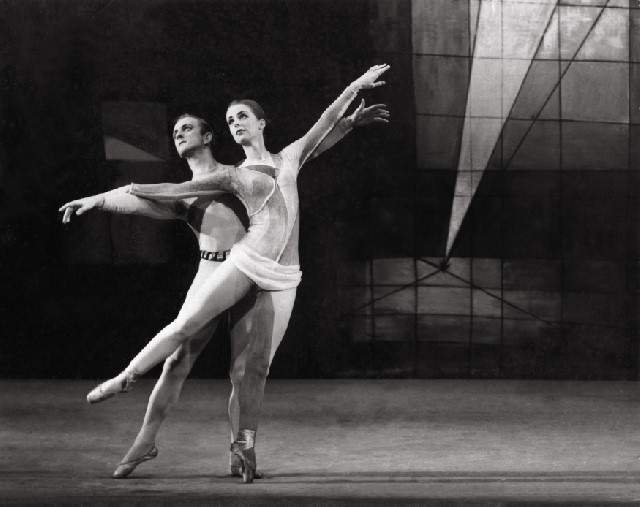

In 1959, New Zealand Ballet and Auckland Ballet Theatre combined in the United Ballet Season, involving dancers June Greenhalgh, Rowena Jackson, Philip Chatfield, Sara Neil and others. The program included Polovtsian Dances from Prince Igor to Borodin’s sensuous score, and Prismatic Variations, co-choreographed by Kerr and Gnatt, to Brahms’ glorious St Anthony Chorale. Music as well as dance audiences in Auckland were astonished, and the triumphant season was repeated with equal success the following year in Wellington, when Anne Rowse joined the cast.

In 1960 a trust to oversee the New Zealand Ballet’s future was formed, and by 1962 Kerr was appointed Artistic Director. His stagings of classics—Giselle, Swan Lake, La Sylphide, The Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker, Coppélia, Les Sylphides, Schéhérazade—were balanced with new works, including the mysterious Charade, and whimsical One in Five. Kerr used compositions by Greig, Prokofiev, Liszt, Saint-Saens and Copland for his own prolific choreographic output—Concerto, Alice in Wonderland, Carnival of the Animals, Peter and the Wolf, The Alchemist, The Stranger. In 1964 he invited New Zealander Alexander Grant who had an established reputation as a character dancer with England’s Royal Ballet, to perform the lead role in Petrouchka, a superb production that alone would have earned Kerr worldwide recognition.

A fire at the company headquarters in 1967 meant a disastrous loss of sets and costumes that only added to the colossal demands of running the company on close to a shoestring budget. Kerr’s health was in an extremely parlous state. In 1969 Gnatt returned from Australia and as interim director, with the redoubtable Beatrice Ashton as manager, kept the company on the road.

Russell had worked closely with Jon Trimmer, the country’s leading dancer, and his wife Jacqui Oswald, dancer and ballet mistress. They later joined him at the New Zealand Dance Centre he had established in Auckland, developing an interesting new repertoire. The Trimmers remember, ‘…Russell would send us out into the park, the street or the zoo, to watch people and animals, study their gait and gestures, to bring character to our roles.’ Kerr also mentored and choreographed for Limbs Dance Company. The NZDC operated until 1977, though these were impecunious and difficult years for the Kerr family. But courage and the sticking place were found, and Russell, as always, let music be his guide.

In 1978 he was appointed director at Southern Ballet Theatre, which proved lucky for Christchurch as he stayed there until 1990, later working with Sherilyn Kennedy and Carl Myers. In 1983 Harry Haythorne as NZB’s artistic director invited all previous directors to contribute to a gala season to mark the company’s 30th anniversary. Kerr’s satirical Salute, to Ibert, had Jon Trimmer cavorting as a high and heady Louis XIV.

His two lively ballets for children, based on stories by author-illustrator Gavin Bishop—Terrible Tom and Te Maia and the Sea Devil—proved highly successful, but there was a whole new chapter in Kerr’s career awaiting. After Scripting the Dreams, with composer Philip Norman, he made the full-length ballet, A Christmas Carol, a poignant staging alive with characters from Dickens’ novel, with design by Peter Lees-Jeffries. (The later production at RNZB had new design by Kristian Fredrikson).

Possibly the triumph of Kerr’s choreographies, and certainly one of RNZB’s best, was Peter Pan, again with Norman and Fredrikson, with memorable performances by Jon Trimmer as an alluring Captain Hook, Shannon Dawson as the dim-witted Pirate Smee, and Jane Turner an exquisite mercurial Tinkerbell.

His sensitively nuanced productions of Swan Lake became benchmarks of the ever-renewing classic that deals with mortality and grief.

Leading New Zealand dancers who credit Russell for his formative mentoring include Patricia Rianne, whose Nutcracker and Bliss, after Katherine Mansfield, are evidence of her claim, ‘I never worked with a better or more musical dance mind.’ Among many others are Rosemary Johnston, Kerry-Anne Gilberd, Dawn Sanders, Martin James, Geordan Wilcox, Jane Turner, Diana Shand, Turid Revfeim, Shannon Dawson, Toby Behan—through to Abigail Boyle and Loughlan Prior.

An unprecedented season happened in 1993 when Russell cast Douglas Wright, the country’s leading contemporary dancer, in the title role of Petrouchka. He claimed Wright’s performances challenged the legendary Nijinsky.

An annual series named in his honour, The Russell Kerr Lecture in Ballet & Related Arts, saw the 2021 session about his own life and career movingly delivered by his lifelong colleague and friend, Anne Rowse. The lecture was graced by a dance, Journey, that Russell had choreographed for two Japanese students who came to study with him. It would be the last performance of his work, the more poignant for that.

Russell was writing his memoirs in the last few years, admitting the struggle but determined to keep going. He said, ‘Writing about my problem with drink is going to be a very difficult chapter.’ Russell had told Brian Edwards in a memorable radio interview decades back, of the exhausting time when his colossal work commitments had driven him ‘to think that the solution to every problem lay in the bottom of the bottle.’ He eventually managed to turn that around and thereafter remained teetotal for life—but by admitting it on national radio, he was offering hope to anyone with a similar burden, himself proof that there is a way out of darkness.

He viewed the sunrise as an invitation to do something with the day. He would bring June a cup of tea but not let her drink it till she had greeted the sun. Recently he took great joy in seeing photos of my baby granddaughter, rejoicing to be reminded of the hope a new life brings to a family.

Russell concurred with the sentiment expressed in Jo Thorpe’s fine poem, The dance writer’s dilemma (reproduced in Royal New Zealand Ballet at 60):

… the thing…

which has nothing to do with epitaph

which has nothing to do with stone.

I just know I walk differently

out into air

because of what dance does sometimes.

Russell Kerr was a good and decent family man, loyal friend, master teacher and choreographer, proud of his work but modest by nature, resourceful and determined by personality, honest in communication, distressed by unkindness, a leader by example. A phenomenal and irreplaceable talent, he was a very great New Zealander.

He is survived by son David, daughter Yvette and their families.

Russell Ian Kerr, QSM, ONZM, Arts Foundation Icon

Born Auckland 10 February 1930

Married June, née Greenhalgh, one son (David), one daughter(Yvette)

Died.Christchurch 28 March, 2022

Sources: David Kerr, Anne Rowse, Jon Trimmer, Patricia Rianne, Rosemary Buchanan, Martin James, Mary-Jane O’Reilly, Ou Lu.

Jennifer Shennan, 3 April 2022

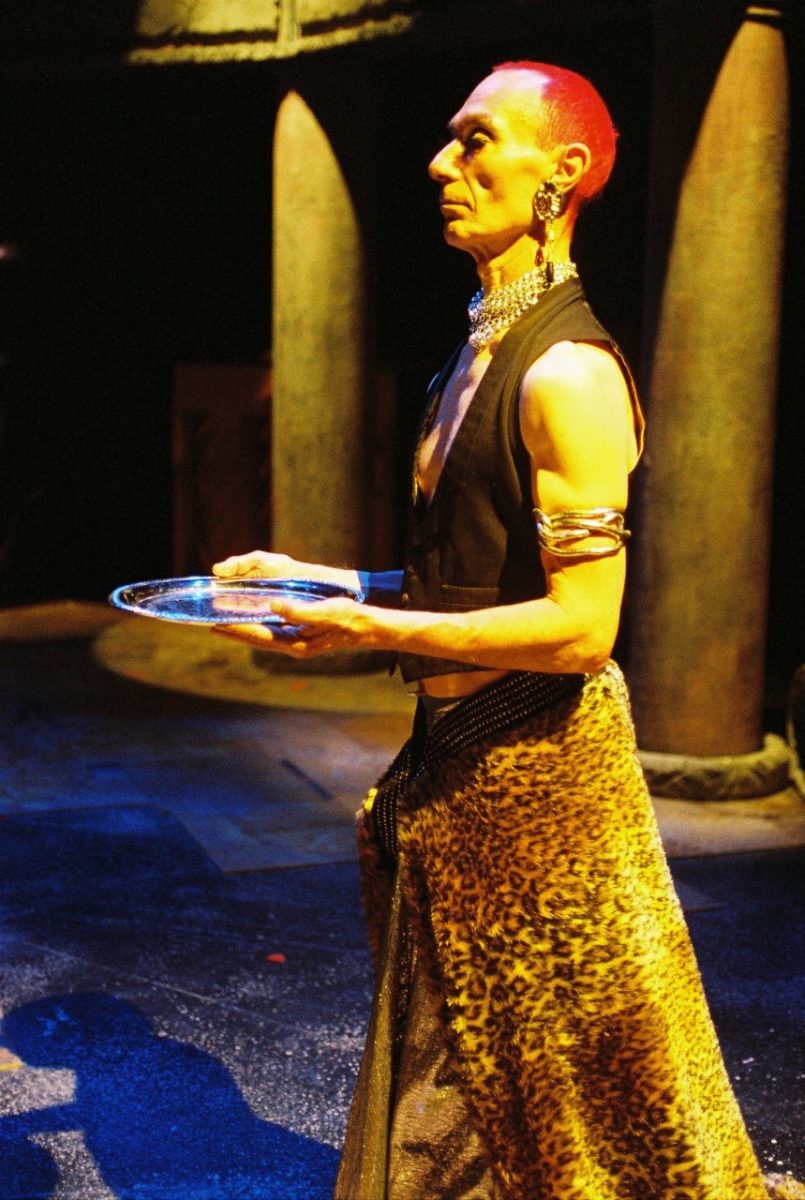

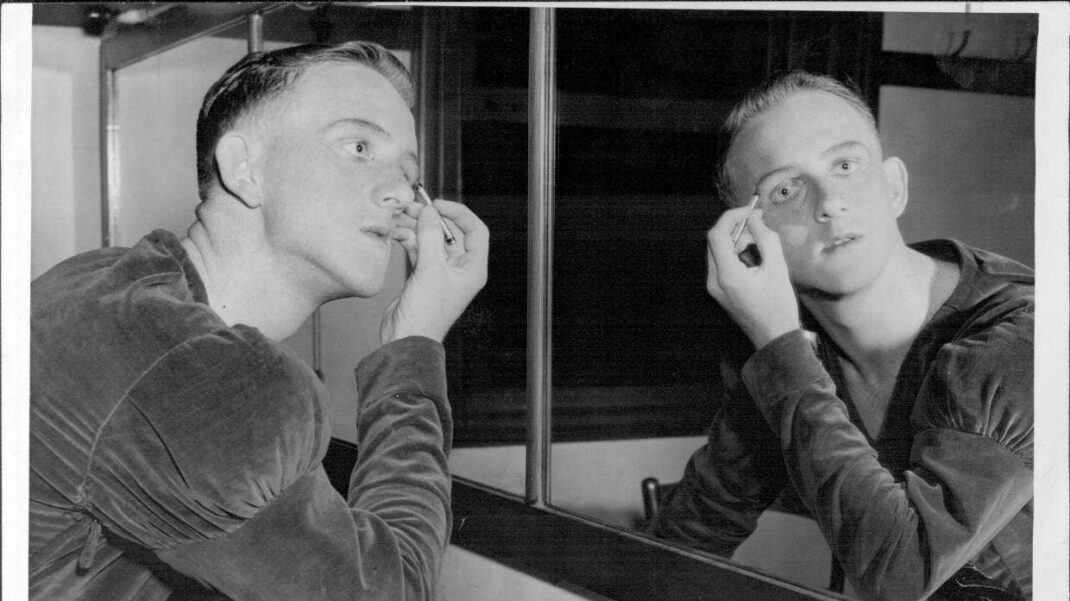

Featured image: Russell Kerr as director of Southern Ballet in 1983

ID; A photo of a white male, slim build, 6′ 2″ tall, wheelchair user with a shaved head, green eyes and sculpted facial stubble, wearing a black at cap, black jumper and a black & grey scarf around his neck. Poised in front of a grey background. Photo credit; Maurice RamirezMarc is a Disabled choreographer, director and dancer. His lecture titled ‘Point of the Spear’ will share his personal experience of the importance of being an advocate for accessibility and inclusion. How, collectively, we all need to work together to be Inclusive in our thinking and actions to make the world equitable for all.

ID; A photo of a white male, slim build, 6′ 2″ tall, wheelchair user with a shaved head, green eyes and sculpted facial stubble, wearing a black at cap, black jumper and a black & grey scarf around his neck. Poised in front of a grey background. Photo credit; Maurice RamirezMarc is a Disabled choreographer, director and dancer. His lecture titled ‘Point of the Spear’ will share his personal experience of the importance of being an advocate for accessibility and inclusion. How, collectively, we all need to work together to be Inclusive in our thinking and actions to make the world equitable for all.