22 November 2021. Te Whaea, Wellington

reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

The Graduation season of NZSD is always a spirited one and, despite numerous disruptions to the year, this 2021 program of nine short works is an outstanding testament to resilience and determination, qualities that dancers are noted for. Such things can be infectious, all to the good since the world needs more of both. It’s the elevation—the leaping, the jumping, the flying, the jeté, the sauté, the entrechat, the gravity-defying stuff that I’m talking about (—the things dancers in retirement tell you they miss the most. It’s metaphor. Normal humans don’t jump, they just walk and maybe run, as common sense dictates they should, so younger dancers are needed to keep the elevation going. If you agree, read on. If you don’t, I’m not sure I can help].

The opening piece, a perfect curtain-raiser, is the Waltz from Act I of Swan Lake, from Russell Kerr’s renowned production for RNZB some decades back, remembered for the integrity of its staging. Swan Lake is not just about the dancing, it’s a story-ballet about love and loss, and the price to be paid for a mistake. Fundamentally it’s a ballet about grief. Kerr has always known how to fully harness the dramatic power of full-length ballets in the theatre, something many attempt but few achieve. He is the consummate force, call that kaumatua, of ballet in New Zealand, and is only aged 91 so there’s time for us to appreciate him yet. RNZB will next year bring back his production of Swan Lake. I remember the closing cameo of its final scene, the cumulative effect of all four preceding acts, a product of Kerr’s humanity and humility, and I have lived by it ever since. This excerpt was staged by Turid Revfeim, a legendary alumna of NZSD, who brought her typical sensibility and acumen to create the enthusiasm and atmosphere of a 21 year old’s birthday party for us all to share. There’s a lot can go wrong at a 21st birthday of course (and the full-length ballet follows through with that) but here it’s a huge bouquet of fragrant roses as a gift for a birthday celebration. Who’s going to say No Thanks to that on the night? Salute to Tchaikovsky, Russell Kerr and Turid Revfeim, to every dancer, and to everyone in the audience since we’ve all been invited to the party, so to speak.

Reset Run, by Tabitha Dombrowksi, lists music by Bach, by Kit Reilly, and by Ravel. I am familiar with Dombrowski as a fine and focussed dancer (earlier in the year she was in the cast of Ballet Collective Aotearoa’s memorable season, and also in Loughlan Prior’s stunning Transfigured Night) but I have not hitherto seen her choreography. It proves a revelation. My anticipation is usually on reserve when several musics for a single choreography are involved, since that might mean fragmentation instead of the coherence that a single composition can support. I need not have worried. Lines, patterns, the front view or the back of each dancer, are thoughtfully modulated to balance light and dark. The cast of eight dancers are in black gear, a white stripe down each arm, and a large oval cut out from the back, allowing light from the shadows to shine on skin. The true choreographic strength, maintained throughout, makes each move consequent from the one before it and gives rise to the one that follows. An initial line-up of couples then become a single couple, then become a group. That beautifully built transition transports me back not 24 hours when I’d watched the magnificent and beautiful lunar eclipse in the night sky. No mean feat to evoke that choreography.

The following work could not have made greater contrast. Dust Bunny, a ziggy number choreographed by Matt Roffe, is an excerpt from his full-length work Cotton Tail. In cabaret mode, it urges all rabbits to run from the farmer’s gun. Some escape, but of course some do not. The animal rights issue here is poignant and well played but I did wonder if some kind of mask or head covering would help the animal representation.

Lucy Marinkovich always develops her work from researched and specific themes. Lost + Found offers a meditation on time, and the ephemeral life of a dance. The opening section, effective in silence, captures both linear and circular time. Further sections layer unison and canon in movement, to the piano music of Jonathan Crayford with atmospheric overtones designed by Lucien Johnson. The climax is a wild and wonderful whirling blur after the manner of dervishes, in the timeless invoking for grace to descend from on high. Where does a dance go when it is no longer being performed? That question is echoed in St.Augustine’s words—’What is time then? If nobody asks me, I know; but if I were desirous to explain it to one that should ask me, plainly I do not know.’ A pointed theme for dance… the most ephemeral of performance arts.

Loughlan Prior, an experienced choreographer with a continually expanding career, made Time Weaver, to music by Philip Glass. A couple dances patterns and lines, holding positions with striking shapes of two bodies, rather than communicating an emotionally engaging pas de deux of the conventional order. The dance comes to seem like the slow-motion capture of an exquisite flower opening—lotus, passionfruit, desert cactus, water lily perhaps—such as David Attenborough would be pleased to have commissioned.

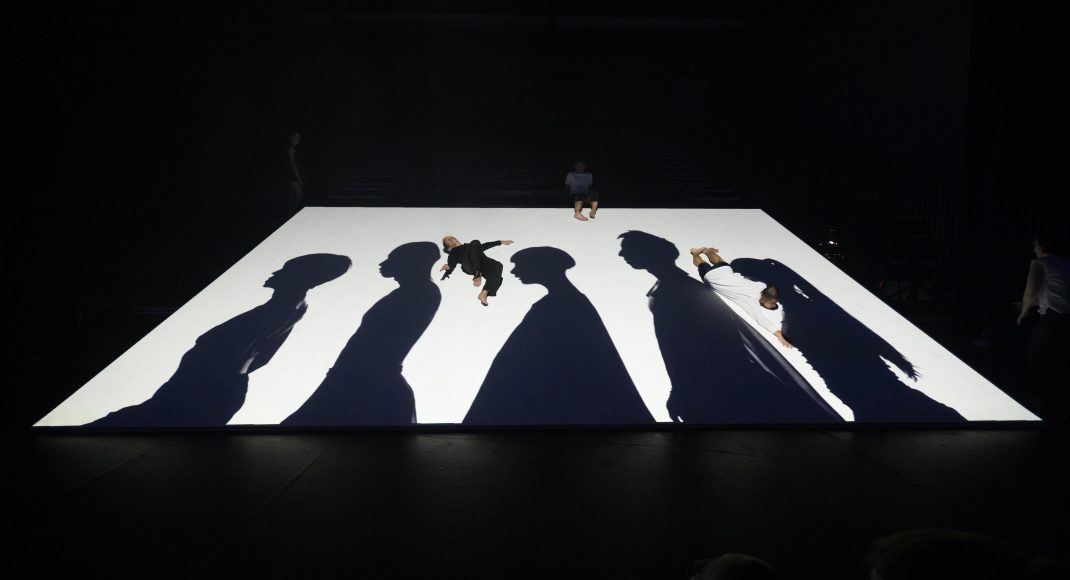

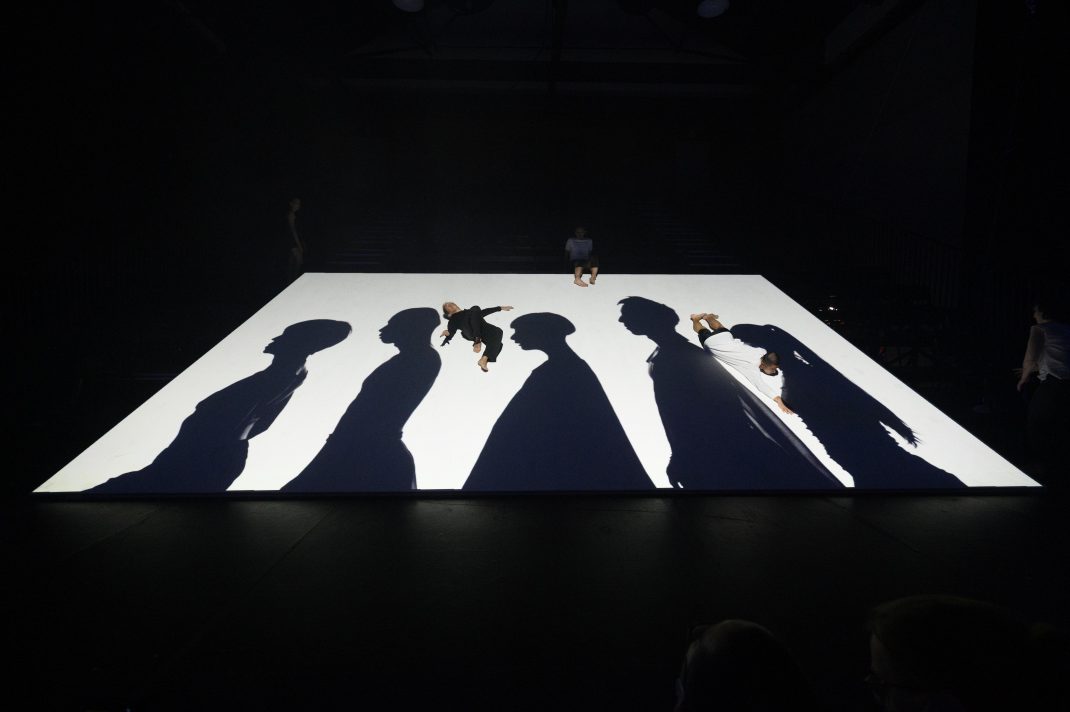

Somewhat Physical by Jeremy Beck rocks with comic satire, but has a serious underpinning. A rambunctious rendering of Rossini’s The Thieving Magpie is resisted by the large group of eleven dancers who stand folded over with arms hanging down. Imperceptibly slowly they unfold to an upstanding position. End of music, bows and applause, thanks for nothing. Chairs are brought in and the dancers set themselves up as an audience. What does that make us? Further sections contain music (Vivaldi, Purcell, Mozart) and movement jokes that question the conventional relationships between what’s seen and what’s heard. The last section seems like a scene from the classic film Allegro Ma non Troppo, with dancers assembled as an orchestra of musicians, flinging their arms off, dancing their hearts out, striking their strings and pounding their percussion. Rossini, Vivaldi, Purcell and Mozart would have loved it—well, it’s for sure at least Mozart would have.

The Bach by Michael Parmenter, to the opening chorus of Bach’s Easter Cantata, is here in an excerpt (from the original made for Unitec season in 2002, and also performed by NZSD in 2006—apart from Swan Lake it’s the only work not a premiere on this programme.) Its presence here answers that question about where a dance goes when it’s not being performed. In this case it resides, it hides, within the music, poised and ready to explode as soon as the music begins—’to celebrate the joy of the Resurrection.’ Fifteen dancers fill the stage with that joy, spiritual and/or religious, and deliver all the moves of a masterwork. You’d want to study this dance for the art and craft of choreography at its best.

In complete contrast follows So You’ll Never Have to Wear a Concrete Dressing Gown, by Eliza Sanders. An experimental piece, constructed in motifs from images in poems penned by the participating dancers. There is further self-referencing in that each dancer wears a shirt imprinted with the face of a class-mate, in a potentially interesting theme. The faces are distorted when the hands of the dancers are placed on the shirts which I find a little disconcerting—and I wait for the wearer and the face to connect during the dance, though that does not happen. This is an enigmatic work not wanting to follow obvious conventions.

Nexus, by Shaun James Kelly, to Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, depicts dancers learning and assembling sequences from classical vocabulary, with frequent motifs of sliding and gliding footwork delivered at speed. I see echoes of Lander’s Etudes, which suits the theme of dancers presenting the movement elements of their art form. In that sense it makes a suitable finale to a Graduation program, though it is the vibes of Parmenter’s work that are still hanging in the air as we dash through the rain to the car park. It’s raining—who cares? We’re dancing.

Jennifer Shennan, 22 November 2021

Featured image: Contemporary Dance Students in Jeremy Beck’s – Somewhat Physical. New Zealand School of Dance, 2021. Photo: © Stephen A’Court