27 May 2016, Lyric Theatre, Queensland Performing Arts Centre, Brisbane

Derek Deane made his Strictly Gershwin for English National Ballet in 2008 when it was shown in London’s cavernous Royal Albert Hall. I have to admit I wondered how it would look on Queensland Ballet in the rather more confined space of Brisbane’s Lyric Theatre. Well I need not have worried. It looked spectacular!

Strictly Gershwin is a show in the true sense of the word—an impressive spectacle. It highlights all kinds of dance from ballet to tap to the charleston. It has an onstage jazz orchestra, largely consisting of musicians from Queensland Symphony Orchestra conducted by a very charismatic Gareth Valentine, and musically it is enhanced by the presence of some outstanding vocalists. It has eye-catching, Hollywood-style lighting and razzle dazzle costumes. And Queensland Ballet is augmented by special guest dancers, a corps of tap dancers and a larger corps of pre-professional dancers. It was some feat to bring this show together. The stage looked a little crowded only occasionally, and a few opening night problems and fumbles will, I am sure, be ironed out in later performances. The audience reaction was loud and appreciative throughout, especially for lead tappers, Kris Kerr and Bill Simpson, with a standing ovation for all at the end.

As the name implies, the show celebrated the music and lyrics of George and Ira Gershwin, from works made for film and musicals to concert hall compositions. The fun begins with the overture in which Valentine displays his dancing skills in addition to his skills with the baton. But the big number from the first half of the program for me was ‘Shall we dance?’ which, with its glamorous black, white and sparkling silver costumes, and its images of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers that are flashed onto an upstage screen, reminded us of those great Hollywood movies of the 1930s. Led by Clare Morehen and Christian Tátchev, it was distinguished by a wonderful range of choreography from quite formal ballroom-style partnering and poses to fast jitterbug moves. What a versatile company of dancers we saw.

In the second half the standout number for me was another big one, ‘Oh, lady be good’, featuring tappers Kerr and Simpson along with Rachael Walsh making a return appearance with Queensland Ballet. They were joined by a guest corps of tap dancers and each and every dancer shone, sparkled and smiled from beginning to end. Such a pleasure to watch.

Overall, my pick of the dancers on this occasion was Lina Kim, beautifully fluid and partnered strongly by Rian Thompson in ‘Someone to watch over me’. She appeared at other times in less featured roles throughout the evening and showed off some fabulous footwork and dancing that carried me away with pleasure as I watched her joyous dancing. I was also swept away by the tango-esque choreography of ‘It ain’t necessarily so’ danced by Yanela Piñera and Camilo Ramos, both perfectly cast to bring a slinky sexuality to the choreography. Then there was Mia Heathcote and Shane Wuerthner in an apache-style duet to music from ‘An American in Paris’. Gorgeous choreography here too especially those subtle changes to the placement of the legs as Heathcote was lifted, turned, lowered and twisted by Wuerthner.

Perhaps the one section that seemed a little messy was the Paris scene. It showed off such a range of characters—people riding bikes, nuns, circus people, characters on roller skates, the full gamut of Parisian characters—that the stage seemed overpopulated to me. Perhaps this was where the Albert Hall was needed? But Strictly Gershwin is a fabulous show, filled with great music and dancing, and an event to be enjoyed rather than analysed. Definitely a major coup for Queensland Ballet.

Michelle Potter, 29 May 2016

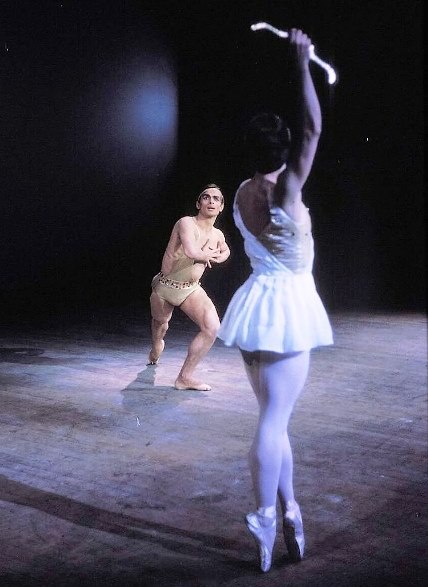

Featured image: Promotional image for Strictly Gershwin. Queensland Ballet, 2016