3 June 2023. Michael Fowler Centre, Wellington

reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

Marc Taddei, music director of Orchestra Wellington (OW), has made the band a major fixture of Wellington’s music scene. A heartily large number of subscribers means there is always a capacity audience in place and the Michael Fowler Centre is no small venue.

Typically, Taddei chooses a theme to connect the different works on any given programme. A recent one, Elemental Forces, featured the mighty Scythian Suite by Prokofiev. It was a staggering experience to hear the enlarged orchestra play the work. I was quite shocked to learn from the program note that Diaghilev had commissioned the score from Prokofiev just the year following Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps, but then declined it even before the composition was finished. (No wonder Prokofiev was sometimes seen leaving Diaghilev’s office in tears). It was 1915, orchestral players were in short supply, mostly being away in the trenches, so the work was never performed and I’m not aware of any subsequent choreography being set to the music. (Diaghilev must have been out of his mind. The final movement of the suite summons a mighty sunrise—probably the most extraordinary sight any human has ever witnessed, even if we do tend to take it for granted, as in ‘the sun will rise again tomorrow’. The dancers would only have needed to start in a crouched position in the dark and to unfold to a standing position into the light, with the slowest motion humanly imaginable. Perhaps Sankai Juku could have managed that? or Cloudgate?

OW’s most recent programme, Myth & Ritual, opened with Richard Strauss’ Salome: Dance of the seven veils. Nobody danced to it—nobody needed to, the music said it all. Then a powerful work for orchestra and saxophone, Zahara, by John Psathas. The soloist, Valentine Michaud, wore a dress (creation might be a better word) that Léon Bakst would have been proud to design.

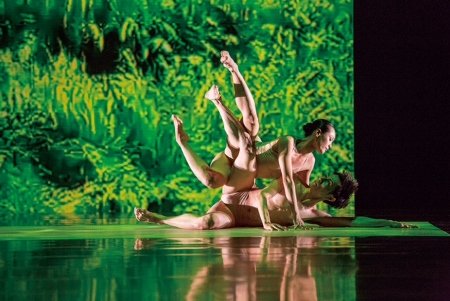

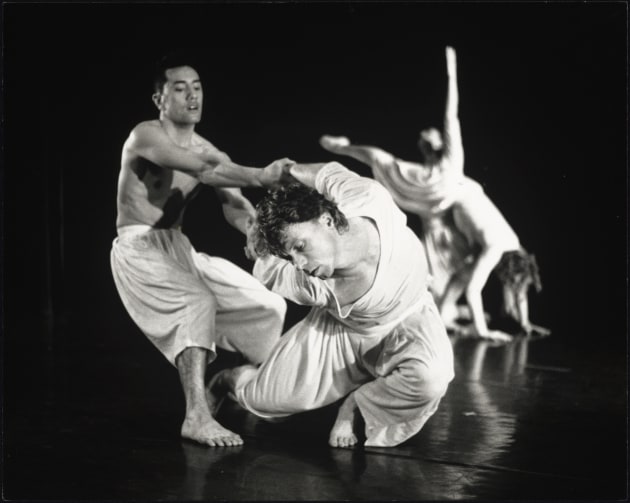

Then followed Bela Bartok’s Miraculous Mandarin in which the orchestra joined forces with Orpheus Choir and with Ballet Collective Aotearoa (BCA). The Michael Fowler Centre may be a large venue but by the time an enlarged orchestra and sizeable choir are in place, there’s not a lot of room left for dancing. It was impressively resourceful then for BCA’s Turid Revfeim, artistic director, and Tabitha Dombroski, choreographic director, to place the cast of six dancers in the high choir stalls, a wide but extremely narrow space, for their playing out of the myth and ritual of this extraordinary work.

Bartok knew what he was doing, even if not everyone has seen what he could see. Note the date of composition, 1918. Whether overt or not, World War One has to be in the subtext of anything produced in Europe at that time. Despite that provenance, the work was received as a scandal and banned on moral grounds but that has not prevented its longevity as a score, even if these 105 years later it can still challenge audiences.

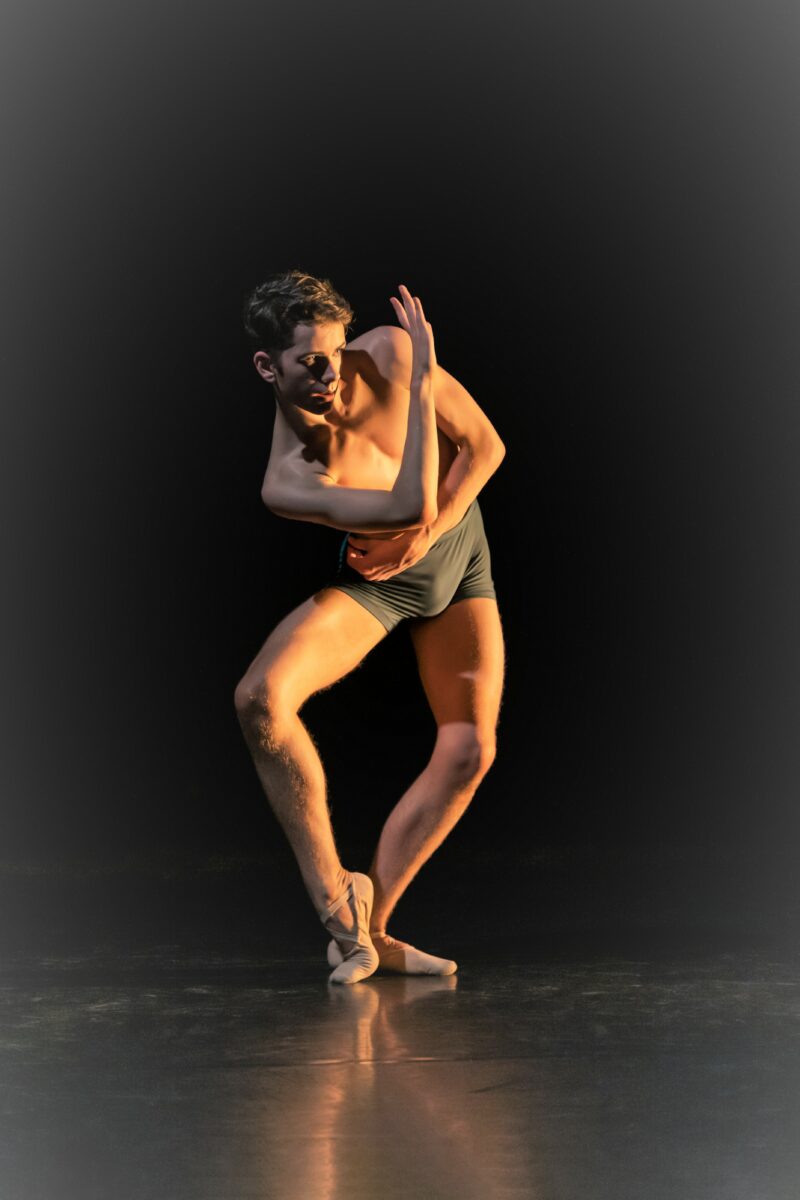

Four street rogues compel a woman to act as seductive target to wealthy passers-by who will then be robbed and beaten to death. One such character emerges, the Miraculous Mandarin, who dies several times, but returns to life. That role was compellingly played by Björn Aslund who faced the orchestra in defiance of the inevitable. The harlot, Mimi, was played with aplomb by Alina Kulikova, and the rough rogues—Alisha Wathen, Zoe White, Callum Phipps and James Burchell—were extraordinarily agile in their clambering through rails and seats. No need to design a set for this—it was there in the architecture of the place.

The dancers are named here because, inexplicably, they were not acknowledged in the printed program on the night— but the imagery they created will linger long in the memory.

Other than that omission, this was a remarkable night at the orchestra that became a night at the theatre. A graphic exhibition in the foyer of the life and work of Bela Bartok, supplied by the Hungarian Embassy, was an added and much appreciated feature.

There is further resonance for those who follow ballet history here that Poul Gnatt, founder of New Zealand Ballet, choreographed Miraculous Mandarin for the national ballet company in the Philippines that he helped to found in 1970s. And in mid 90s, the then artistic director of the Royal New Zealand Ballet, Ashley Killar, choreographed Dark Waves to Bartok’s Music for strings, celeste and percussion. He based the ballet on a short story by Vladimir Nabokov, and gave to Jon Trimmer one of his finest roles. The work was toured to America (where it impressed the New York critics) though was never performed publicly in New Zealand. (I’d got lucky and seen a studio rehearsal before the company went on tour. They returned to find various arts agencies were trying to close the company down. Triumph to those who said No to that).

There are still a number of dancers from the original cast easily to be located, who would willingly coach a new cast. Killar is still active in the ballet world and lives in Sydney, so there’s not a lot to stop the work being staged again. It’s redolent with New Zealand provenance.

Jennifer Shennan, 5 June 2023

Featured image: Rehearsal for Myth and Ritual