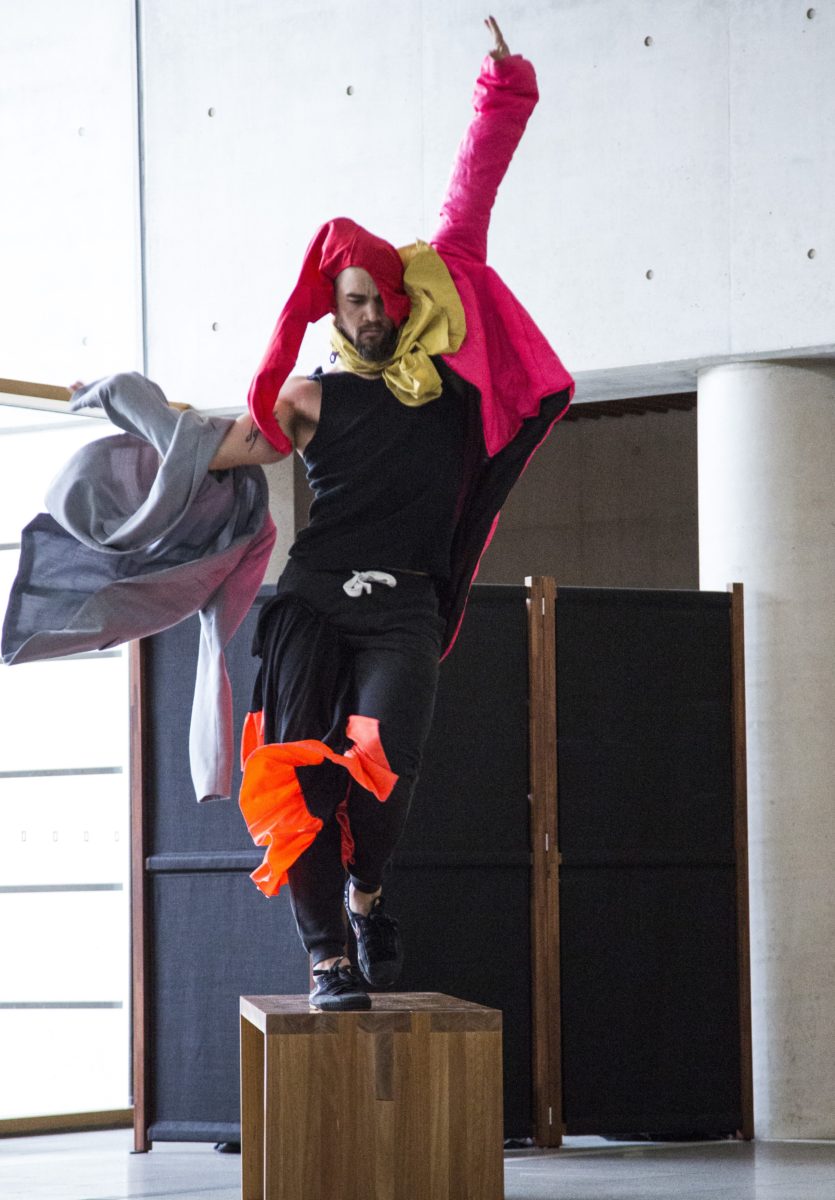

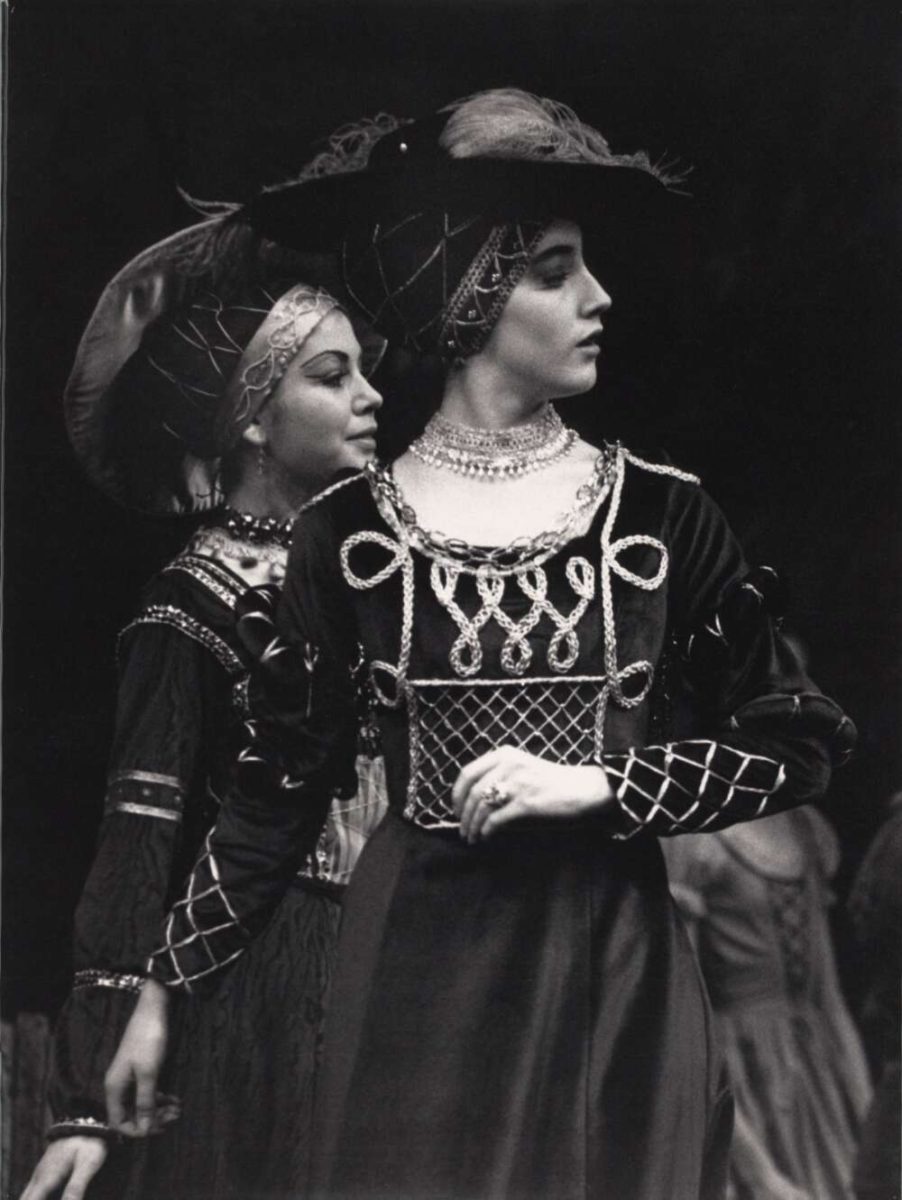

- Gray Veredon on choreography

I am pleased to be able to post some interesting material sent to me by New Zealand-born choreographer, Gray Veredon. He has just loaded the first of a series of video clips in which he talks about his aims and ideas for his choreographic output. He uses examples from his latest work, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which he mounted recently in Poland. See below.

- Alan Brissenden (1932–2020)

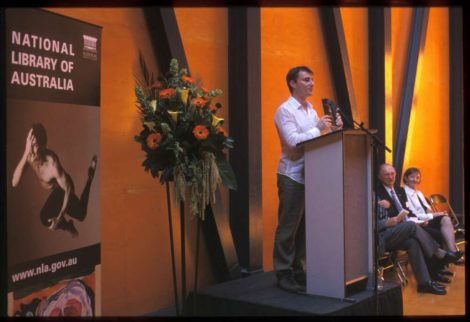

The dance community is mourning the death of Dr Alan Brissenden, esteemed dance writer and outstanding academic from the University of Adelaide. Alan wrote about dance for a wide variety of magazines and newspapers from the 1950s onwards and was inducted into the Hall of Fame at the Australian Dance Awards in 2013.

As I looked back through my posts for the times I have mentioned Alan on this site, it was almost always for his and Keith Glennon’s book Australia Dances: Creating Australian Dance, 1945–1965. Since it was published in 2010, it has always been my go-to book about Australian dance for the period it covers. No gossip in it; just the story of what happened—honest, critical, carefully researched and authoritative information. Very refreshing. Find my review of the book, written in 2010 for The Canberra Times, at this link.

A moving obituary by Karen van Ulzen for Dance Australia, to which Alan was a long-term contributor, is at this link.

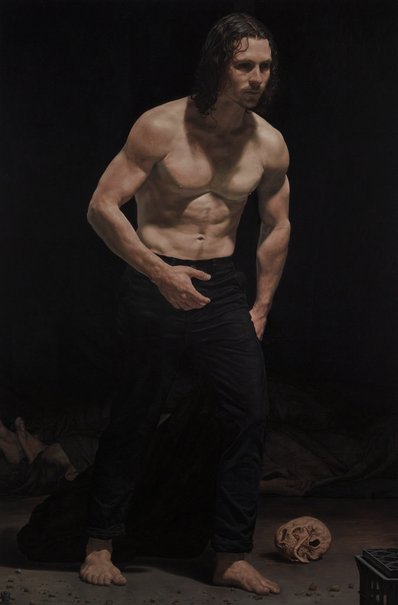

- Jack Riley

It was interesting to see that Marcus Wills’ painting Requiem (JR) was selected as a finalist for the 2020 Archibald Prize. While Wills states that the painting is not meant to be ‘biographical’, the (JR) of the title stands for dancer Jack Riley. Riley began his performing career as a Quantum Leaper with Canberra’s youth group, QL2 Dance. After tertiary studies he has gone on to work with a range of companies including Chunky Move, Australian Dance Party, and Tasdance.

See the tag Jack Riley for more writing about him and his work on this site.

- Jake Silvestro

The first live performance in a theatre I have been to since March took place in September at the newly constructed black box theatre space at Belconnen Arts Centre, Canberra. It was a circus-style production called L’entreprise du risque. It featured Frenchman Bernard Bru and Australian Circus Oz performer Jake Silvestro, along with two young performers who trained at Canberra’s Warehouse Circus, Imogen Drury and Clare Pengryffyn.

While the show was somewhat uneven in standard, the standout performer was Jake Silvestro, whose acts on the Cyr wheel showed incredible balance and skill in general.

But whatever the standard, it was a thrill to be back watching live theatre again.

- Kristian Fredrikson. Designer. More reviews and comments

In Wellington, New Zealand, Kristian Fredrikson. Designer is being sold through Unity Books, which presented the publication as its spotlight feature for its September newsletter. Follow this link. It includes Sir Jon Trimmer’s heartfelt impressions of the book, which I included in the August dance diary.

An extensive review by Dr Ian Lochhead, Christchurch-based art and dance historian, appeared in September on New Zealand’s Theatreview. Apart from his comments on the book itself, Dr Lochhead took the opportunity to comment on the importance of archiving our dance history. Read the full review at this link.

Royal New Zealand Ballet also featured the book in its September e-newsletter. See this link and scroll down to READ.

Back in Australia, Judy Leech’s review appeared in the newsletter of Theatre Heritage Australia. Again this is an extensive review. Read it at this link.

- Press for September

‘Capital company.’ A story on Canberra’s professional dance company, Australian Dance Party. Dance Australia, September-November 2020, pp. 31-32.

Michelle Potter, 30 September 2020

Featured image: Giovanni Rafael Chavez Madrid as Oberon and Mayu Takata as Titania in Gray Veredon’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Ballet of the Baltic Opera Danzig, 2020. Photo: © K. Mystkowski

–

–