29 & 30 November 2023. Te Whaea, Wellington

by Jennifer Shennan

NZSD offered alternating programs, one of Classical and one of Contemporary dance, across a five-day season. There was a consistently high standard of dancing from all the students across both programs, though a number of audience members admitted they would have liked to see pieces from each stream combined onto one program, since they were only able to attend a single performance. That too would have demonstrated the range of technical and aesthetic strengths that the School offers, and varied the choreographic experiences for us all.

The timing of the season makes it effectively a Graduation though it is not billed as such, so we surmise it’s the Third Years who are graduating, or Second Years who may be leaving if they have already been offered a contract somewhere. All the students deserve congratulations for staying the distance, and we wish them courage and stamina as they seek out pathways to long and fruitful dance careers. There’s a rich legacy, since the School’s beginning in 1967, of many graduates who have done just that, and that list would read as tribute to all the former and present faculty and students who have made the world a better place by dancing.

The Classical program comprised four works all by American choreographers with, unusually, all of them staged by one person, Betsy Erickson, an American visiting teacher to the School. Meistens Mozart was choreographed in 1991, by Helgi Tomasson, long-time artistic director to San Francisco Ballet (recently retired—and replaced now by the wunderkind of international ballet, Tamara Rojo—it will be of considerable interest to see how she handles the American ballet scene after ten tears at the helm of English National Ballet). The work was lively and danced with enthusiasm, to a set of songs by Mozart and contemporaries.

Aria, by Val Caniparoli, is a striking solo for a masked male, danced here with much aplomb by Joshua Douglas (a 2nd year student already headed for a career opportunity at Queensland Ballet). The Handel sarabande is sublime dance music and the choreography etches its way into a beautiful response to that, inviting a fine performance. It would have been fascinating to watch a Contemporary dance student, maybe a female, in a following repeat performance, to help us all see and appreciate where technique and virtuosity give way to character and emotion. Therein lies theatre.

Vivaldi Concerto Grosso, choreographed in 1981 by Lew Christensen, also of San Francisco Ballet, gave further lively opportunity to a larger cast, though had a similar choreographic structure and style to the opening work.

A piece that reflected New Zealand’s ballet legacy would have provided welcome contrast—from Bournonville, Fokine, Kerr or Veredon for example. The current NZSD faculty includes Anne Gare, Turid Revfeim, Sue Nicholls, Nadine Tyson, Vivencio Samblaceno—most of them graduates of NZSD and all of them formerly with RNZBallet, so staging something from the Company’s repertoire would have been in safe hands, and acknowledged the relationship between the two enterprises.

Another work from Val Caniparoli, made in 1980 for Seattle’s Pacific Northwest Ballet, used the familiar and playfully percussive Schulwerk of Carl Orff for Street Songs, that captured a young and optimistic mood and fitting finale to the evening.

The following evening’s Contemporary dance program had an altogether different sense of occasion, with Vice Regal and Ambassadorial attendance, and opened with a substantial whakatau (Maori welcome) delivered by Tanemahuta Gray.

The first work, a premiere this season, Thank You, was by Felix Sampson, a graduate of NZSD, now in DanceNorth company in Townsville, Australia. The tongue-in-cheek opener with a cleverly judged tone was a spirited piece, and the large group of dancers made a well-bonded ensemble.

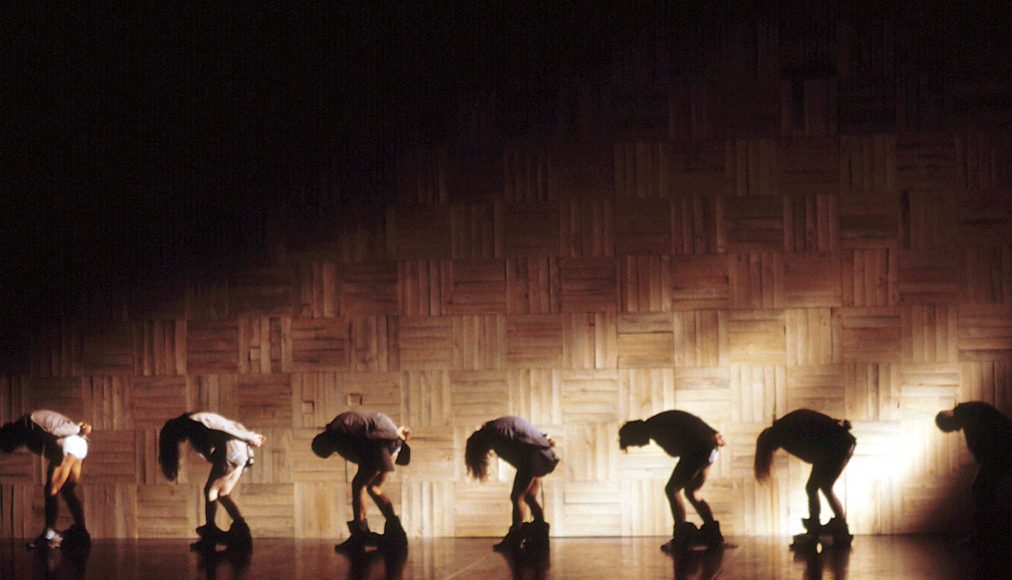

Outlier, also a premiere, by Kit Reilly, a recent NZSD graduate, was a standout choreography with reflections of sounds, rhythms and forms in natural surrounds. At times there were poetic echoes of the kinds of creatures that David Attenborough brings to our attention, and that is high praise from me. We can look forward to more dance-making from Reilly since he clearly has what it takes to shape movement into ideas, and vice versa.

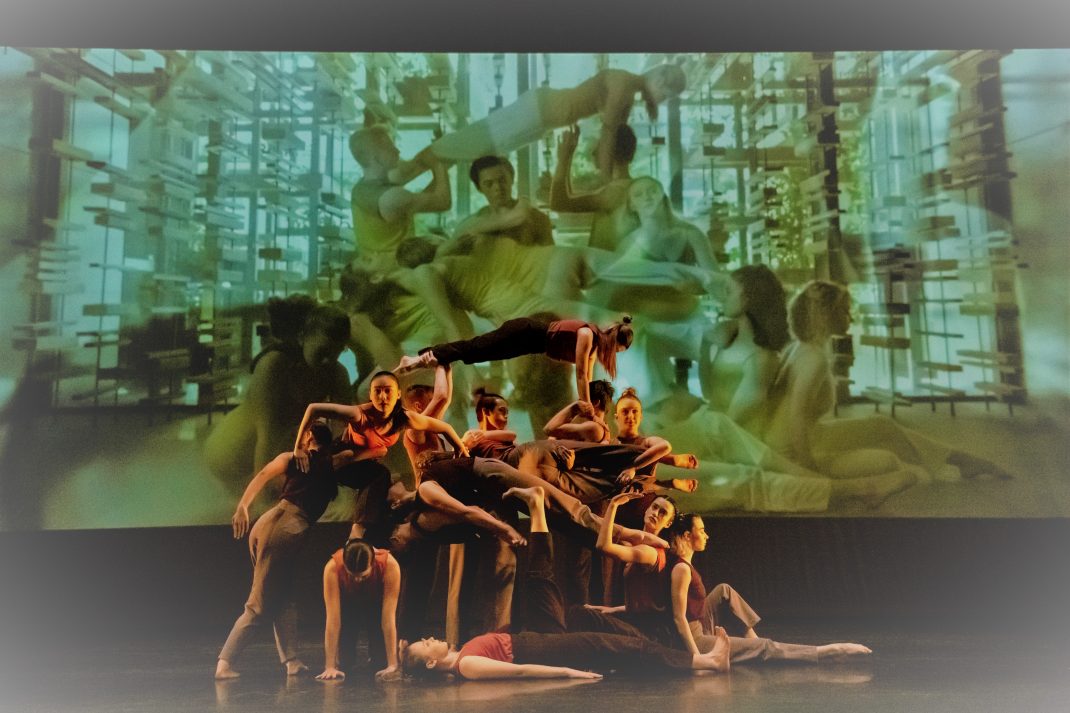

Excerpts from The Beginning of Nature by Australian choreographer Garry Stewart, to music by Brendan Woithe, used solos and duos as well as group work that made for intriguing counterpoint. It’s hard to know from these excerpts what the complete work is like, the program note reads that it ‘…delves into territoriality, senescence and symbiosis, offering a glimpse into life’s beauty.’ A solo danced by Mārie Jones will stay with me a long time however. (A second-year student but leaving NZSD and heading for Canada, I’m guessing she will make waves wherever she dances).

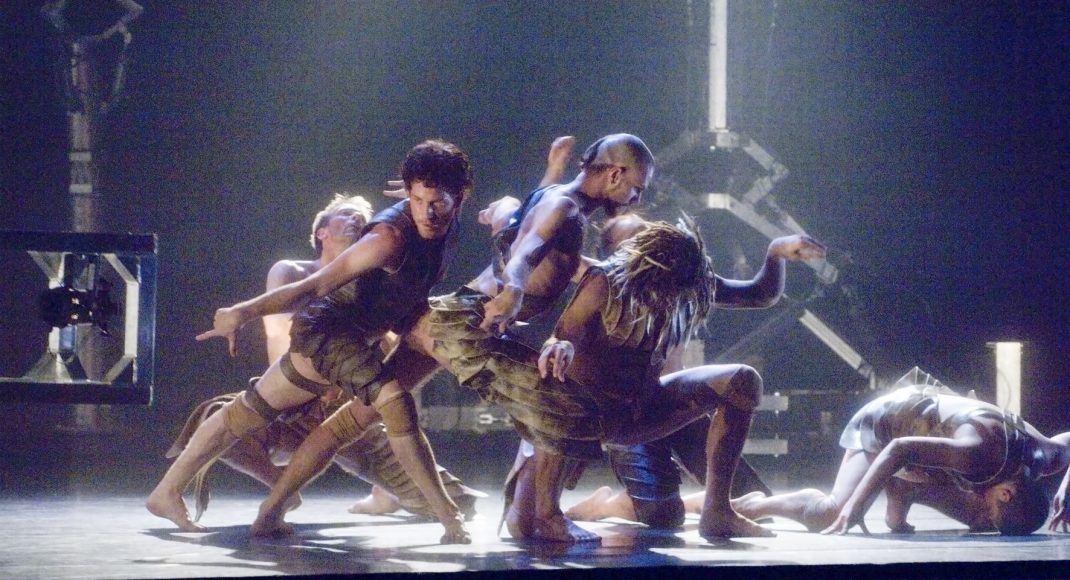

Re:Action, by Ross McCormack, to a combination of musics, is a series of responses by the dancers to a large rock-like prop, designed by Max Deroy, and named ‘the force’. The deliberately slow pace of movement did not seem to aim for any denouement or cadence to help us in our own response to the choreography.

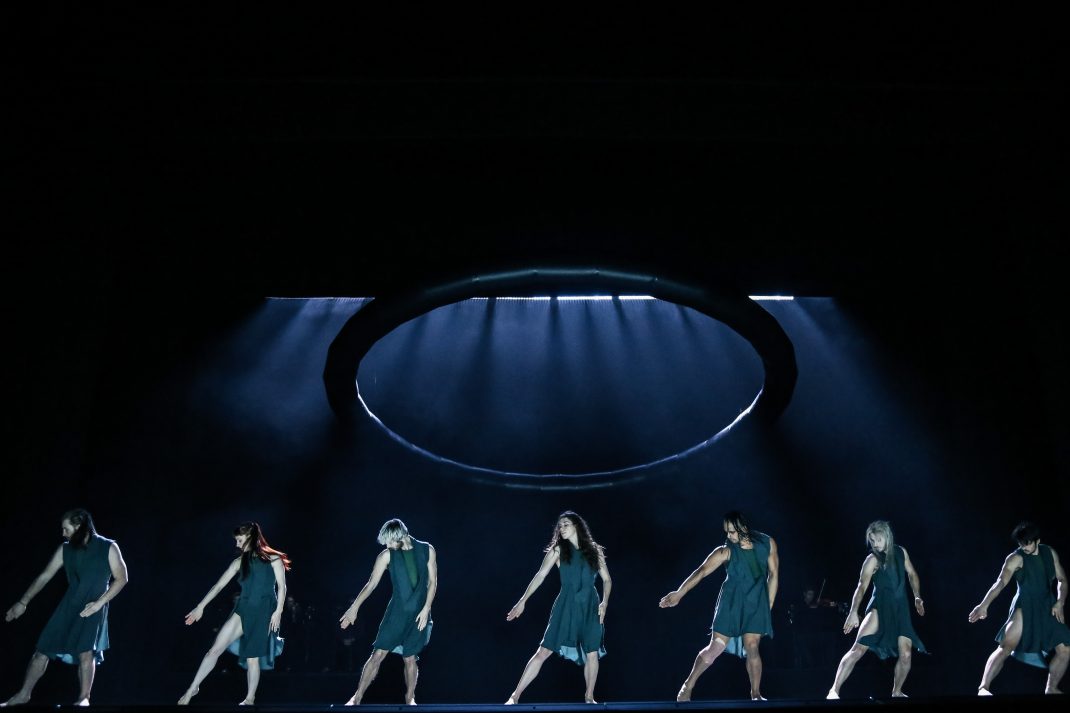

The final work, Incant—summoning the lost magic of intuition, by Amber Haines, of DanceNorth, is an attractive set of large and smaller group pieces, with some effective sculptural shapes caught in a series of arm movements.

All of the students in both programs gave completely committed performances and they should know we wish every one of them a long and wonderful career.

A note on strobe lighting: A warning in the foyer that there will be strobe, and also loud music, during the performance is a bit like the road sign ‘Beware of falling rocks.’ Not a lot you can do about it except close your eyes—which is what I always do when strobe starts. Not an ideal way to review a dance performance I admit, but I’m not prepared to compromise on that.

And a comment in retrospect—that Classical and Contemporary dance training share much more similarity than difference. The profession needs dancers who can do everything a choreographer asks, so a combination of works from both NZSD programs would help us to celebrate what dance in the theatre can do for us all.

Jennifer Shennan, 5 December 2023

Featured image: Joshua Douglas in Val Caniparoli’s Aria. New Zealand School of Dance Performance-Season, 2023. Photo: © Stephen A’Court