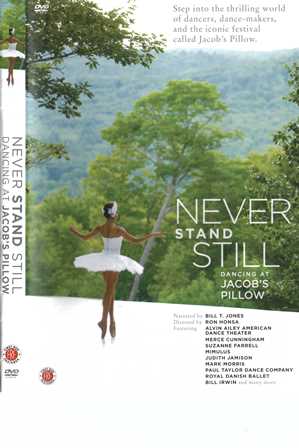

New York-based dance writer, Joan Acocella, whose critical writing I much admire, has spoken of Jerome Robbins’ Dances at a gathering, along with Paul Taylor’s Esplanade and Mark Morris’ Gloria as ‘benchmark works of the sixties/seventies youth cult, with their gangs of fresh-faced young folk skipping and running and falling to the accompaniment of high-art music’ and as being ‘in exaltation of what is plain and openhearted and innocent as opposed to what is fancy and fake.’* The featured image above shows Marianela Nuñez and Alexander Campbell in the Royal Ballet’s production of Dances at a gathering, and it seems to me indicative of the human qualities that Acocella describes. As the work progresses those qualities become more and more obvious.

Dances at a gathering opens and concludes quietly, introspectively perhaps? In the opening sequence, Alexander Campbell enters quietly from the downstage Prompt side and dances a solo in which swinging arm movements and expansive jumps across the stage predominate. He exits on the OP side, but before doing so makes a questioning gesture with one hand. Where is the gathering? At the very end the cast of ten, five women, five men, stand on stage, often in stillness, before they leave arm in arm. The gathering has concluded.

In between there is so much beautifully poetic choreography, sometimes with the flavour of character work, the mazurka in particular. This of course befits the Polish rhythms that permeate much of the selection of piano music by Frederick Chopin (spelled Fryderyk Chopin on Royal Ballet publicity) to which the work is performed. Often the movement seems simple, deceptively so I hasten to add. There are no noticeably ongoing, or clearly defined relationships between the dancers and Robbins is recorded as saying, ‘There are no stories to any of the dances in “DAAG” There are no plots and no roles. The dancers are themselves dancing with each other to that music in that space.’** But there is much scope for us to see personalities. We see it through movement and through facial expressions, and through the recognition the dancers show to their fellow performers throughout. It is indeed a gathering, and the individuality of each dancer is very clear.

If I had to choose a favourite section from the astonishingly good performance by the entire cast, I would go for a section led by Laura Morera. The section begins with a solo by an effervescent Morera. She is playful and sexy, and performs with beautifully timed highlights. The sequence has those overtones of character dancing but is equally strong in classical movement. Morera appears to be playing to an invisible partner. Towards the end of the section two prospective partners appear, but neither shows the interest she hoped to generate within them. With a shrug and a smile she leaves the stage. Transfixing I thought.

The duet between Marianela Nuñez and Federico Bonelli, which led into the finale, was another highlight, full as it was with caring touches, longing glances, and clear admiration for each other. Yasmine Naghdi also had some wonderful moments of fast and detailed movement. Then from Bonelli there were those fabulous double tours ending in a full plié in first position. What an elegant and exciting performance from the entire cast! They explain why in the video clip below.

Dances at a gathering was made by Jerome Robbins in 1969 for New York City Ballet and entered the repertoire of the Royal Ballet in 1970. The stream we were offered during the Royal’s 2020 digital season was recorded during a performance this year, 2020. It featured ten of the Royal Ballet’s star dancers, Marianela Nuñez, Francesca Hayward, Yasmine Naghdi, Laura Morera, Fumi Kaneko, Alexander Campbell, Federico Bonelli, William Bracewell, Luca Acri and Valentino Zucchetti. The varied selection of Chopin’s piano music was exquisitely played by by Robert Clark.

Dances at a gathering has never been part of the repertoire of the Australian Ballet and, as far as I am aware, has never been shown live in Australia. I paid £3 to have access to this stream, and it was worth every penny and more, especially given that viewing was possible a month (it is available until 25 October)! Perhaps in the future David Hallberg might consider adding it to the Australian Ballet’s repertoire? On the other hand, I can imagine it sitting very nicely on Queensland Ballet.

Michelle Potter, 8 October 2020

Featured image: Marianela Nuñez and Alexander Campbell in a screenshot from Dancers at a gathering. The Royal Ballet, 2020

* Joan Acocella, Mark Morris (New York: Farrar Strauss Giroux, 1993), p. 87.

**Deborah Jowitt. Jerome Robins. His life, his theater, his dance (New York: Simon & Shuster, 2004), p. 387.

Jowitt, in the book mentioned above, gives an excellent account of the development of Dances at a gathering in chapter 16, pp. 381-388.