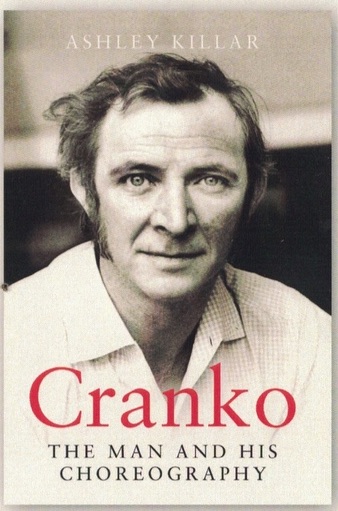

Cranko. The man and his choreography by Ashley Killar

Matador/Troubador Publishing

ISBN. 978-0-646-86603-1

reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

This biography of John Cranko is a deeply researched, widely contextualised and beautifully written account of the life and work of a major choreographer of mid-20th century. There is meticulous detail in the documentation and analysis of Cranko’s vast choreographic output, both within the text and in appendices. Ashley Killar has drawn on that oeuvre, as well as many of Cranko’s letters to friends and colleagues, to evaluate the teeming imagination and artistry, musical ear, lively sense of wit and satire, the devoted loyalty to friends and colleagues, the generous personality, the frankness over frustrations when things went wrong, the ability to move on to the next thing, the excesses in a sometimes reckless lifestyle—all the good and some of the bad in a life fully lived but ended too soon. You come to know the man through coming to know his works, not just by reading a list of titles but by experiencing the texture and timing of the choreographies. That’s skilful dance writing.

Killar was a member of Stuttgart Ballet from 1962 to 1967 so he knew Cranko well. The book Is a devoted tribute to the man and his work, but in no measure is it simply hagiography. The contexts of socio-political history and related arts that open several chapters, and are also summarised in the appendix of choreography, are welcome reminders of a 20th century world. The contrasts of living conditions and morale in South Africa (where Cranko was born, in 1927), in post-war England (where he lived, danced and began to choreograph), in a divided post-war Germany without a single national ballet company (where he flourished, from 1961 to 1973), in Russia (where there were intriguing interactions within the political control of ballet, and the dancers visiting from Stuttgart had to step through a door in an iron fire-curtain lowered to end the applause but the audience would not cease applauding), and in America (where on a number of tours, thanks to Sol Hurok, Cranko met with great success with audiences, who loved the narrative and dramatic power of his works that their own dance-makers had not produced. There was also ongoing disdain from certain critics, Arlene Croce the most vocal among them… as though to say, ‘If you loveq—Balanchine then you must hate Cranko’. OK, so did that mean the reverse was true? (KIllar’s pen is wiser and more tempered than Croce’s was).

These contextual accounts are briefly but tellingly written and the book should appeal to a much wider readership than just ballet afficionados. It places the man in his dances, his dances in society, and societies in their response to his dances. That’s resonant choreography and insightful appreciation combined.

There were seemingly unconventional work practices in all his career. Cranko never had an office but would sit in the company canteen, use the phone on the counter, and be at all times accessible to the dancers he considered members of a family—holding no truck with the typical power and control that many a ballet company director adopts in the vain pretence that this secures leadership. The accounts around England’s Royal Ballet and that company’s ethos under Ninette de Valois’ directorship, come under the spotlight. Peggy van Praagh by contrast emerges as a genuinely joyful and encouraging figure who instantly recognised Cranko’s talent and knew how to help him rein in so that his best ideas could emerge, that less would be more. Her own long life generously devoted to dance is well caught here.

You could look at the listing of dancers in the Stuttgart company and fledgling choreographers stimulated and nurtured by Cranko—they are among the best in the world, and New Zealand gets an entry. There is further resonance for New Zealand in that Martin James danced the title role of Eugene Onegin many times, rating it one of the most demanding and rewarding in his own remarkable performing career. It is but one example of how the dance profession becomes a kind of country in its own right, crossing over the political and historical boundaries defined by nationalism and history.

Cranko’s longstanding friendships with designer John Piper, and with composer Benjamin Britten (whose Gloriana, Peter Grimes, Prince of the Pagodas, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Bouquet Garni were choreographed to) are covered. Figures in the English ballet world include Cranko’s relationship with the somewhat caustic de Valois, the idiosyncratic Frederick Ashton, as well as his camaraderie with Kenneth MacMillan, and are notable. It is Peggy van Praagh who emerges as an independent thinker and visionary to my mind. I was intrigued to hear of the early influence on Cranko of the work of Rudolf Laban and Kurt Jooss—and later of his appreciation of the technique and style of Martha Graham, and suspect van Praagh was instrumental in this open-mindedness. Cranko’s partnership with Anne Woolliams as influential teacher at Stuttgart and her later appointment to the Australian Ballet, where van Praagh was a pioneering and spirited leader, provide a further connection to ballet in this part of the world.

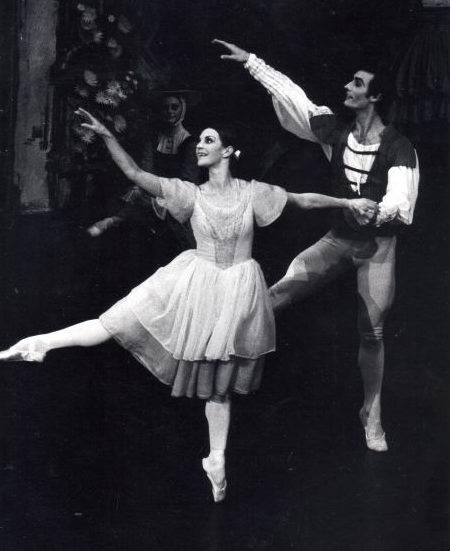

From a hugely prolific body of work it is probably the early Cranks revue, the now largely forgotten Prince of the Pagodas, his The Lady and the Fool, Romeo & Juliet, Onegin and The Taming of the Shrew for which he is most remembered.

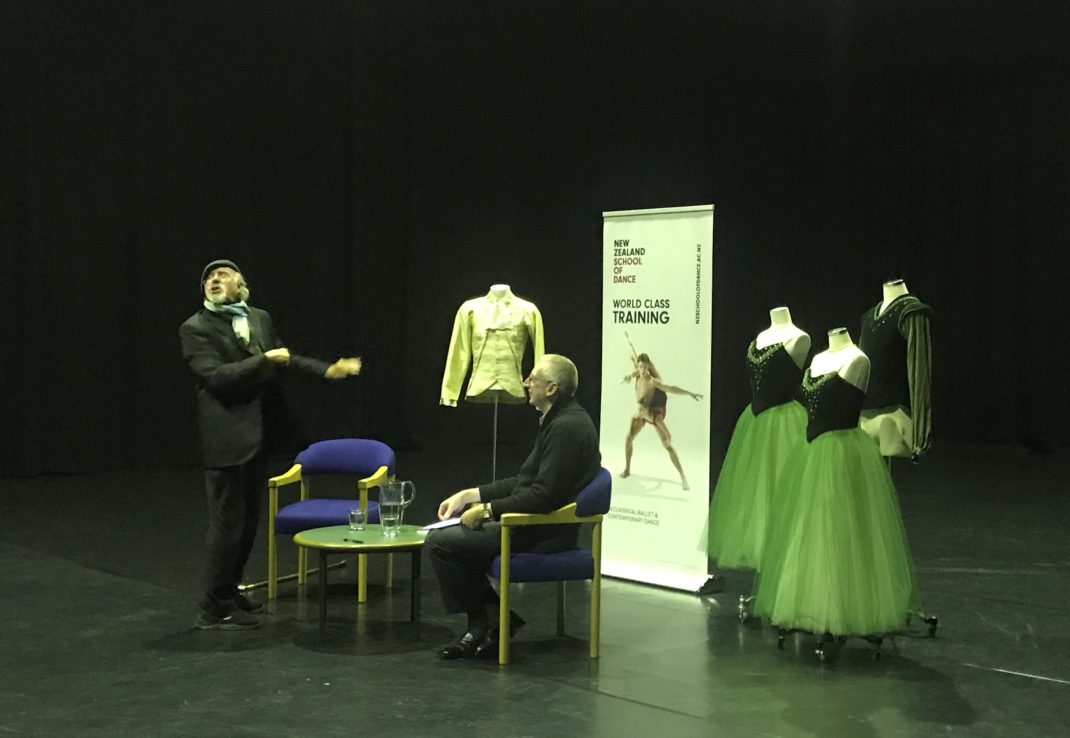

Marcia Haydée was legendary dancer and company stronghold at Stuttgart for many years. Among the young dancers in his company whose choreography he encouraged and nurtured are John Neumeier, Jiri Kylian, Gray Veredon (New Zealand’s own) and Ashley Killar himself (artistic director of RNZBallet 1992-1995, whose No Exit and Dark Waves were among the most dramatically incisive works in the company’s entire repertoire).

Cranko’s legacy speaks volumes and Killar has done him proud.

Jennifer Shennan, 13 December 2022

Cranko. The man and his choreography is available through Bloch’s ballet centres (including by mail order). Alternatively, the book is available to order through bookstores, or direct from ![]() www.troubador.co.uk/bookshop/biography/cranko/

www.troubador.co.uk/bookshop/biography/cranko/

Go to ![]() www.crankobiography.com for more information.

www.crankobiography.com for more information.