From Jennifer Shennan

In September 2013 Anne Rowse and I flew to Melbourne for the Arts Festival…mainly in pursuit of Fabulous Beast, with Keegan-Dolan’s astonishing double-bill of Petrushka and The Rite of Spring. We relished equally the chance to catch up with dear Harry, knowing he would say yes to the suggestion of a performance, an exhibition, a forum, with coffee dates, dinners and suppers tucked in everywhere. We knew he would have seen half the Festival already, and would offer us incisive and helpful opinions on what was what. Good times coming.

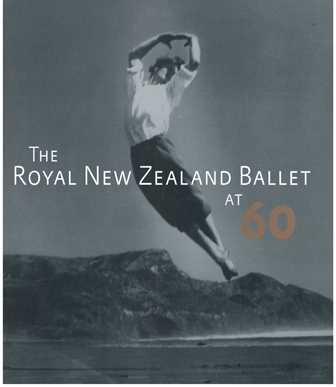

Tor and Jan Gnatt, bless them, met us at the airport. We were all so excited to connect so soon after the launch of Royal New Zealand Ballet at Sixty that the Gnatt boys forgot where in the airport they had parked their car. We had lots of conversation catch-up while they hunted every floor of the car park for the elusive vehicle. (Their father, Poul, would have remembered the rego plates of the vehicles he had parked next to, and been mortified by this scenario.)

We found an el cheapo hotel, and fell into welcoming Melbourne as though we had always lived there.

Harry had already seen Fabulous Beast, and had a number of reservations about it. He nonetheless joined us for the forum, and had the grace to acknowledge afterwards that the incisively brilliant mind and wit of Keegan-Dolan helped him to retrospectively re-evaluate the choreography.

Harry instructed us which exhibitions to visit, and suggested a local dance group’s performance, preceded by a meal with his friend Robin Haig (they had worked together in 1940s in London…a typical Harry trait…ever loyal to his many friends and colleagues). The meal was great fun but the performance, which entailed the slow lighting of many candles, then their being equally slowly extinguished, then equally slowly re-lit, we found suffocatingly pretentious. (In all his years in New Zealand Harry always attended everything, and was supportive in principle of all dance endeavour, but was occasionally heard to mutter upon leaving ‘Well, the best thing about it is that they’re doing it.’ After leaving this particular evening he muttered, ‘Well, the worst thing about it is that they’re doing it).’

But as we rode the tram back into Melbourne central, an extraordinary event took place. A young Aboriginal woman, striking in appearance, but in a state of very great distress, was remonstrating up and down the tram carriage with all the world about many things. Not drunk, but totally out of control, in a wrath of emotion and heartbreak, pain, confusion and grief that was moving, even terrifying, to witness. No one knew how to help. Harry quietly started speaking a commentary to us, tracing various chapters of Australia’s colonial history, engaging us to listen, and to thus avoid making eye contact with the woman pacing the tram, as any such eye contact can become a trigger to further volatility. There was such an informed sympathy, empathy even, in Harry’s words…no judgment, no reproof. His calm, informed, sad summarising of history, at the same time offering us a degree of protection from a potentially explosive situation, was much as I imagine Thomas Keneally might have behaved.

Bi-cultural issues and opportunities within dance were part of Harry’s long-term thinking. During his time at Royal New Zealand Ballet (‘the happiest years of my life’ he was often heard to say), he commissioned Tell Me A Tale from Gray Veredon, with design by Kristian Fredrikson, to music by New Zealand composer Matthew Fisher. In that talisman piece, with leading roles created by Jon Trimmer and Kerry-Anne Gilberd, was an encounter between Maori and Pakeha, a haka within the ballet given extraordinarily powerful expression by Warren Douglas. No more telling moment has occurred in the company’s entire repertoire history, and it is a great loss that the work has not been retained.

Warren was also spectacular as the hilarious Cook in the Veredon/Fredrikson Servant of Two Masters, with Jon Trimmer as Pantalone and Harry as Dr Lombardi, tottering about wearing a twelve foot long striped scarf that threatened to trip him and everybody else on stage all evening. A fine film of this ballet is held in the New Zealand Film Archive, and is well worth the three hours it lasts. (We subsequently lost Warren to AIDS and many hearts were broken).

Harry took his title of Artistic Director Emeritus very seriously. He wrote to Ethan Stiefel upon his appointment, wishing him well, highlighting the related arts in New Zealand as a context for choices of ballet repertoire, and encouraging an awareness of Maori issues. Despite clearly failing health, Harry was still taking an interest in the news of the appointment of Francesco Ventriglia in late 2014. He asked us to send reports on any indications or statements of artistic vision as they appeared. This company was Harry’s baby, and he loved it as parents love their children.

Harry’s own term as artistic director, from 1981 to 1993 with business manager Mark Keyworth, was a resilient team effort and there has probably never been a stronger partnership between artistic and business directors in the company’s history. What those two achieved on the miniscule resources of the day was breathtaking. Harry also maintained a very close relationship with the New Zealand School of Dance under the direction of Anne Rowse. They shared so much knowledge and awareness of repertoire in the wider dance world that the students were fortunate beneficiaries of that rapport, also the strongest partnership in the history of both institutions.

The chapter Harry wrote for the book, Royal New Zealand Ballet at Sixty, recounts many highlights of his term. It was an inspired early move to celebrate in 1983 the company’s 30th anniversary with a Gala season, inviting each previous director to select a choreography. We had No Exit from Ashley Killar (this was Harry’s choice, and a pearler) and Bournonville from Poul Gnatt. Perhaps the abiding achievement of this project was Harry’s diplomacy in welcoming Poul back to his adopted country after various chapters of less than happy history since his departure in 1963.

In 1986, Harry’s production of Swan Lake, again in tandem with Fredrikson, was a theatrical tour de force. He always remained very sad it was not retained in the company’s repertoire. Harry was a youngster in vaudeville performance. His formal schooling had turned into supervised backstage correspondence while on tour, but his bright brain and fabulous memory ensured a lifelong passion for learning across many disciplines. Harry’s close rapport with Graeme Murphy saw him in several cameo roles … as Court Photographer in that astonishing Swan Lake, a charming friend of Clara in the inspired Nutcracker, only upstaged by his tap dancing on roller skates in Tivoli (and was certainly worth my trip across the Tasman to check it out).

In an adult education course I will teach in Wellington early in 2015, one of the sessions will be dedicated to a survey of Harry Haythorne’s term as artistic director of Royal New Zealand Ballet …’the happiest years of my life’. Well, you said it Harry.

Jennifer Shennan, Wellington, December 2014

Featured image: Jon Trimmer (left) as the wealthy Pantalone and Harry Haythorne as Dr Lombardi in A Servant of Two Masters, 1989. Photo: Martin Stewart, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington. PACOLL-8050-36-04