- The best of …

My ‘best of …’ for 2014 will appear with the ‘best of …’ comments by others in the February/March edition of Dance Australia. But looking ahead to the coming year, perhaps the show I am most looking forward to (of those that have been announced so far of course) is the triple bill by the Australian Ballet that will feature Twyla Tharp’s In the Upper Room.

Looking back through my archive of reviews, here’s what I wrote in Dance Australia in 1997 when the work premiered in Australia during the first year of Ross Stretton’s directorship.

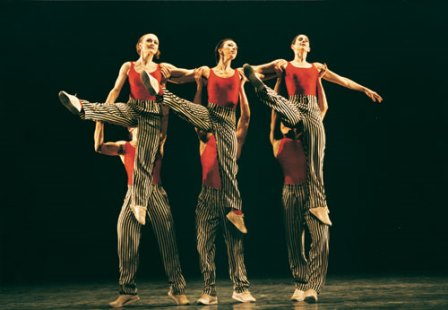

… [In the] Upper Room has relentless drive and a choreographic eclecticism that balances the old and the new, the classic and the contemporary. It frequently insists on a cross-over between styles and the rubbery, sleight-of-hand-looking movements that we associate with Tharp often suddenly slow down and take on a kind of genteel quality. Other times the refinement of the classical vocabulary is made to look less rarefied as it collapses into more loose-limbed movements or is performed in counter balance with more contemporary-style steps. And in all this, Tharp’s work never looks stylistically judgemental. Dance is dance.

Since then I have seen Upper Room performed by both Pacific Northwest Ballet and American Ballet Theatre and, quite honestly, despite the galaxy of stars in each of those companies, neither company has given me the thrill that I got from the Australian Ballet’s performances of 1997. They were addictive experiences. I kept going back. Let’s hope the Australian Ballet rises to the occasion in 2015! In the Upper Room opens in Melbourne in August in a triple bill entitled 20:21

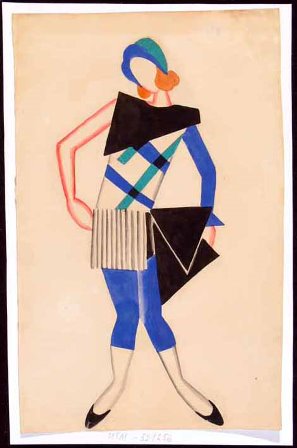

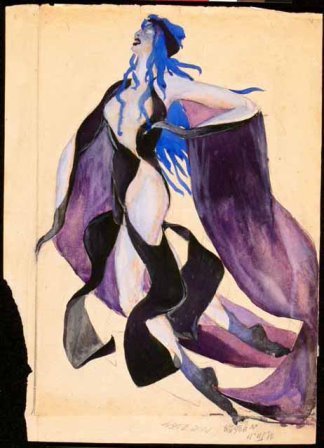

I don’t have access to Australian Ballet photos of this work. The image below is from the Birmingham Royal Ballet’s website.

- Oral history

In December, I received an interesting comment on an oral history interview I recorded with Edna Busse in August 2014. It is available among many other comments, at the end of this post. The comment generates many issues associated with oral history as a research tool, most of which have been debated in conferences and the like dealing with the role and uses of oral history.

I drew on material from twenty-five National Library oral history interviews, and two radio recordings from an Adelaide program called ‘Theatreland Spotlight’ (preserved in the National Film and Sound Archive), in my recent biography of Dame Margaret Scott. I think the book would have lost a lot had I not had access to that material. Some of those whose interviews I used are now dead—Charles Boyd, Sally Gilmour, Paul Hammond, Geoffrey Ingram, Bruce Morrow, Noël Pelly, James Penberthy, Marie Rambert, Ray Powell, Kenneth Rowell, Peggy Sager, and Gailene Stock are among them—and their thoughts and recollections for the most part are not available in other formats.

None of this, however, takes away from the fact that interviewees may embroider upon their experiences, or misremember events (sometimes quite badly), which is the thrust of the comment. Using oral history as source material is beset by problems and is at its best when used judiciously and when the information is cross checked with other sources (if possible). Any source material is only as good as the historian who uses it.

I value immensely the comment on the Edna Busse interview as it comes from someone who was closely involved with the Borovansky Ballet and who has given me a contact to enable me to pursue the issue further. But it doesn’t take away from the value of the interview, just makes me ponder further on the care with which this very personal form of source material needs to be approached.

- Press for December 2014 [Online links to press articles in The Canberra Times prior to mid 2015 are no longer available]

‘Professional productions too few. Michelle Potter’s top picks for 2014’. The Canberra Times, 23 December 2014, ARTS p. 6.

Michelle Potter, 31 December 2014