Tradition—classical program

21 November 2018. Te Whaea, Wellington

by Jennifer Shennan

New Zealand School of Dance is one school with two discrete streams, Classical Ballet and Contemporary Dance. Their Graduation season is always an uplifting affair as the fledgling dancers leave the nest where they have spent the past three years in intensive training. We can guess they’ll each be wishing for just one thing—life as a dancer. I can see no reason why they shouldn’t all get what they wish for, though over time that will, for some of them at least, stretch to include ‘teacher’ and ‘choreographer’ as well.

There are students from New Zealand, including Maori and Pasifika, and several countries beyond, Australia and Asia. The seeds of teacher training included in the curriculum here would help them find work for life back home if not here. We won’t be done with our life on Earth until everyone, in every country, has had a chance to dance, if only as a way to enhance recognition of choreographic masterpieces when they see them. There was such a masterpiece on each of the two programs and I’m shivering to tell you about them, as well as share a few thoughts about possible future directions.

The Ballet program, Tradition, opened with an excerpt of La Sylphide, from Bournonville heritage. Nadine Tyson (alumna of the School and a long-term dancer with RNZB), staged the work which was danced with care and love. The fact that Henning Albrechtsen, the world’s finest free-lance Bournonville teacher, had a residency at the School just last year, will have paid off in the students’ understanding of this demanding and darling style, renowned for its contained vigour and life-affirming ebullient spirit within ballet heritage. (A pity no program note could remind us that Poul Gnatt was for years the most renowned interpreter in the world of the leading role of James. His oral history includes a fabulous story about that, and relates to New Zealand).

It was Gnatt who first raised the voice to form a School to serve the needs of the Company he had already established in 1953. It would be 1967 before the National School of Ballet opened its doors. A paragraph to that effect could be included within the printed program, with further reference to its 50 year history recently written by Turid Revfeim (alumna of the School and long-term dancer with RNZB). History will not go away just by our staying quiet, and a background program essay is needed to pick up and weave back together the threads between School and Company that have recently, by neglect, been torn asunder.

It is deeply satisfying to sight a young dancer in the back row of the corps of La Sylphide who, as have others, used her time at the School to develop the technique and to hone the style that she simply did not have three years ago, but that she will now carry back to her Asian homeland and thus spread good in the world. She may not know that this sentence is about her, but I do. Well done all.

The following Tarantella, by Balanchine, 1964, a romp to Gottschalk music, gave a superb chance to a pair of young students to strut some marvellous stuff. There’s also a link across to Bournonville via the tambourine, but these days dancers with tambourines are so polite. If you’re going to dance with one, don’t you need to thrash hell out of it and rattle the discs to let everyone know that dancing with one is different from dancing without one?

Sfumato by Betsy Erikson (we need program notes to identify the choreographers) was an extended work, from 1986, to Boccherini, but that does not carry the vitality of the Baroque repertoire that preceded his era. The work is staged by Christine Gunn, long-term teacher at the School, and by Nadine Tyson. The dancers all do well, but the challenges of choreographic structure on this music remain. In past years there has been one work on the program done to live piano accompaniment (after all, the two best ballet pianists in town—Phillip O’Malley and Craig Newsome—are on the staff here) but this line-up did not offer that opportunity.

Then followed After the Rain, a pas de deux by Christopher Wheeldon, and the theatre fell silent. A man and a woman, dancing to Arvo Pärt’s music, Spiegel im Spiegel, for piano and violin (offering resonance back some years to alumna Raewyn Hill’s memorable choreography, Angels with Dirty Feet, to the same music). Every moment, every gesture, every position held and line followed, every lifting, sliding and lowering, shows choreographic mastery. They are not having sex, they are making love, in any generous understanding of those words you care to bring to reading them. It’s a triumph for a School anywhere to include Wheeldon’s work in its Graduation program. It was rehearsed by Qi Huan, premier dancer for years at RNZB, and the calibre of his work shines through the students’ performance.

Emerge, a solo for a male, by Australian choreographer Louise Deleur, was a world premiere. Also rehearsed by Qi Huan, it received a focused performance.

Christopher Hampson’s Saltarello, choreographed for RNZB in 2001, is a smart and sultry number and a fitting finale to this satisfyingly varied program. Here staged by Turid Revfeim, again a School alumna as well as long-term Company stalwart dancer, teacher, choreographer and administrator there, and now teacher at the School, it gives scope to a large cast who find the style and pizzaz to mix humour into its moves.

2018 marks 20 years since Garry Trinder became Director of the School and there can be no doubting his commitment to the wellbeing and developing careers of the students. Chair of the Board, Russell Bollard, spoke in tribute. The small print in the program reminds us that dancer and staff reps are included on the Board. Any decent workplace these days knows to represent the spectrum of its people among its governance. It’s a mark of confidence, high morale, respect, common sense and fair play. Top marks to this institution for that

Jennifer Shennan, 23 November 2018

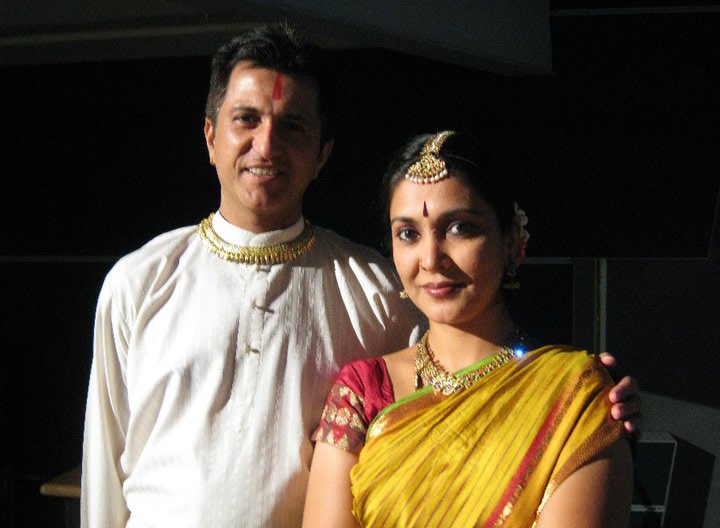

Featured image: Jaidyn Cumming and Bo Hao Zhan in August Bournonville’s La Sylphide. New Zealand School of Dance Graduation, 2018. Photo: © Stephen A’Court