Hot to Trot is an annual dance event in Canberra and is designed to give senior Quantum Leap dancers (who are mostly in their teens!) the opportunity to create their own choreography. Despite the issues that have plagued the arts community over the past several months, Hot to Trot 2020 went ahead in QL2’s black box space in Gorman Arts Centre, complete I should add with emphasis on the physical distancing of audience members. Two short films and eight live productions were presented.

What especially attracted me in this year’s program was the ability of the choreographers to use the performing space to advantage. They understood how to arrange their dancers, and any props they used, within the space, sometimes filling it, sometimes using corners, diagonals, upstage and downstage areas, and so forth. It reflects well on the QL2 Dance program where, from the beginning, young, prospective artists are taught stage techniques as well as dance technique.

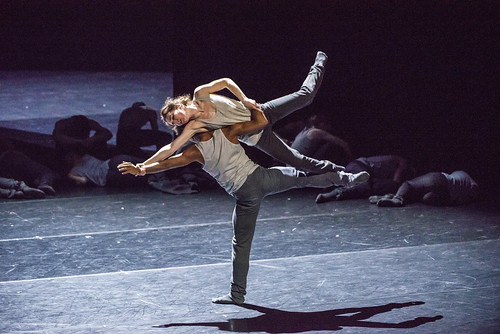

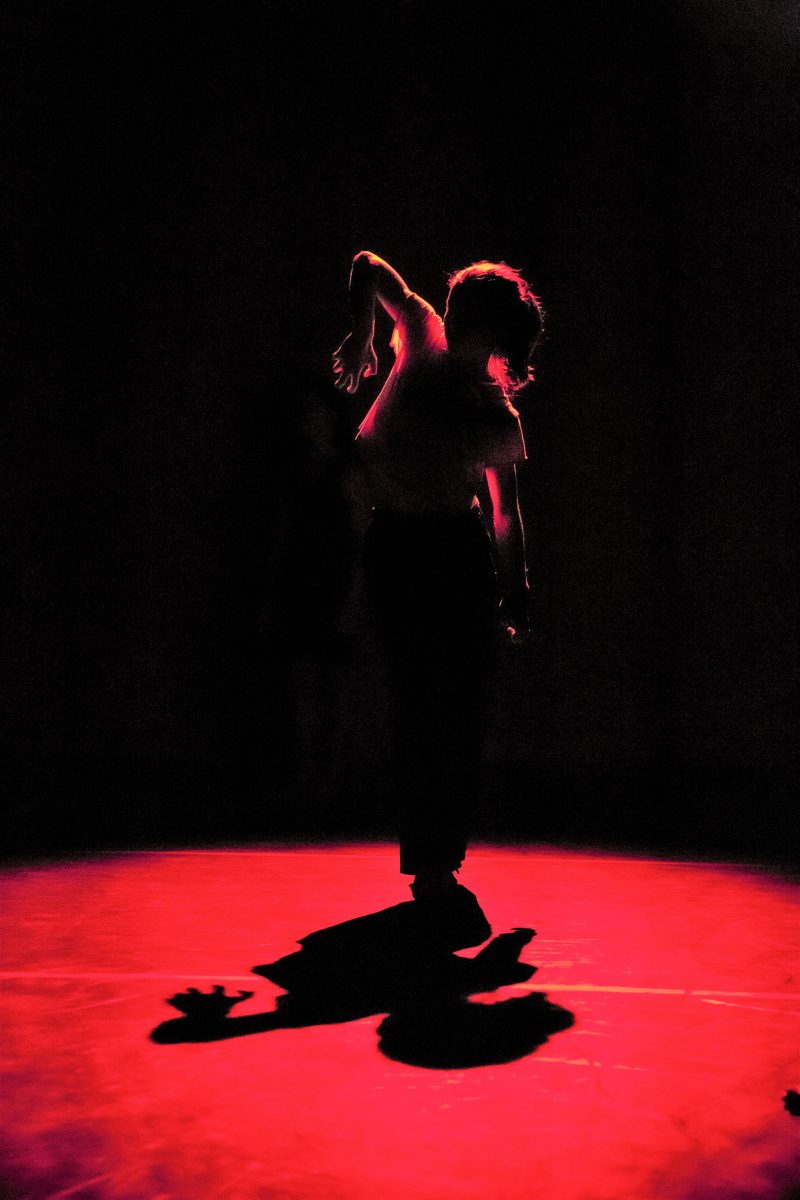

But one work stood out for me—Danny Riley’s Similar, Same but Different. It was essentially a reflective work that examined the connections Riley sees as existing between him and his older brother, Jack, who is now a professional dancer and choreographer. In essence it was a replay of a work made by Jack Riley, which we saw on a film in the background. Danny Riley danced the same choreography for the most part and began by wearing a white jacket that his brother had worn—it was rather too long for him, which in itself spoke to us about those family connections. As the work progressed Danny Riley removed the white tuxedo and replaced it with a short, black jacket of his own—it fitted nicely! But, finally, that too was discarded and we understood that Danny Riley was his own man but with influences from family connections. It was a moving work that unfolded logically and clearly but that was complex in the ideas that it generated in our minds.

I loved that Riley didn’t see the need to use text as an essential addition to his work. Which brings me to the criticisms I have of this Hot to Trot program, and other such programs at QL2. I really wish that there could be a stronger realisation by these young choreographers that dance has the capacity to engage and comment within itself. It doesn’t need to have a text to which dancers react and which is meant (I think) to help the audience understand what is going on in the work. Speaking onstage during a performance is a particular skill and requires training. So often with QL2 productions, in which the spoken word is used, it is not easy to hear or understand what is being said. Not only does this reflect a lack of voice training, but also that the spoken text is often not well integrated with the score, which means that the words are drowned out by the score. And pretty much always, in my opinion, the spoken text seriously detracts from the dance aspects of the work.

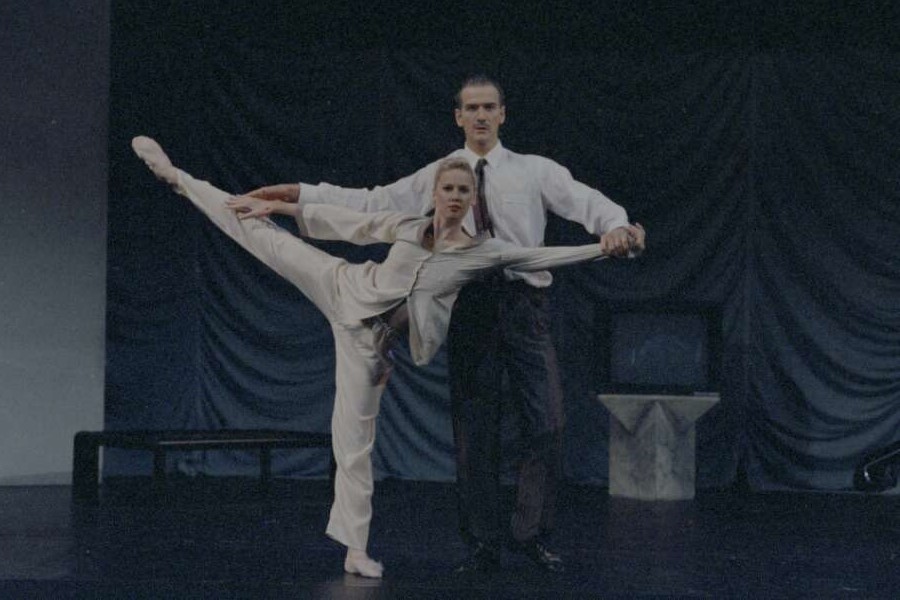

The other issue that bothers me concerns the subjects young choreographers often choose as inspiration—subject matter that is quite abstract, or philosophical. Wayne McGregor or William Forsythe might be (and are) good at using conceptual issues as the basis for a dance work, and Tim Harbour at the Australian Ballet is also moving in this direction with particular skill, but they are experienced, professional artists who understand what dance can do best. It communicates through movement.

But to return to the Hot to Trot program itself, the other work I especially enjoyed was the short film by Natsuko Yonezawa, which opened the program. Called Flowering, it was filmed during rehearsals for the recent Leap into Chaos project by QL2 and focused on group movement. The raw footage was assembled and edited so we saw a kaleidoscope of images that recalled flowers growing in ever-changing, ever-expanding patterns. To me the film often looked like origami, being made or being made to move. It was quite beautiful and a great introduction to the program.

Other works on the program were created by Magnus Meagher, Alyse and Mia Canton, Courtney Tha, Lillian Cook, Pippi Keogh, Hollie Knowles, Rory Warne, and Sarah Long.

Michelle Potter, 25 November 2020

Featured image: Danny Riley in Similar, Same but Different. Hot to Trot, 2020. Photo: © Lorna Sim