14 March 2024. St James Theatre, Wellington

reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

Belle—A Performance of Air is a theatrical event of monumental proportions.

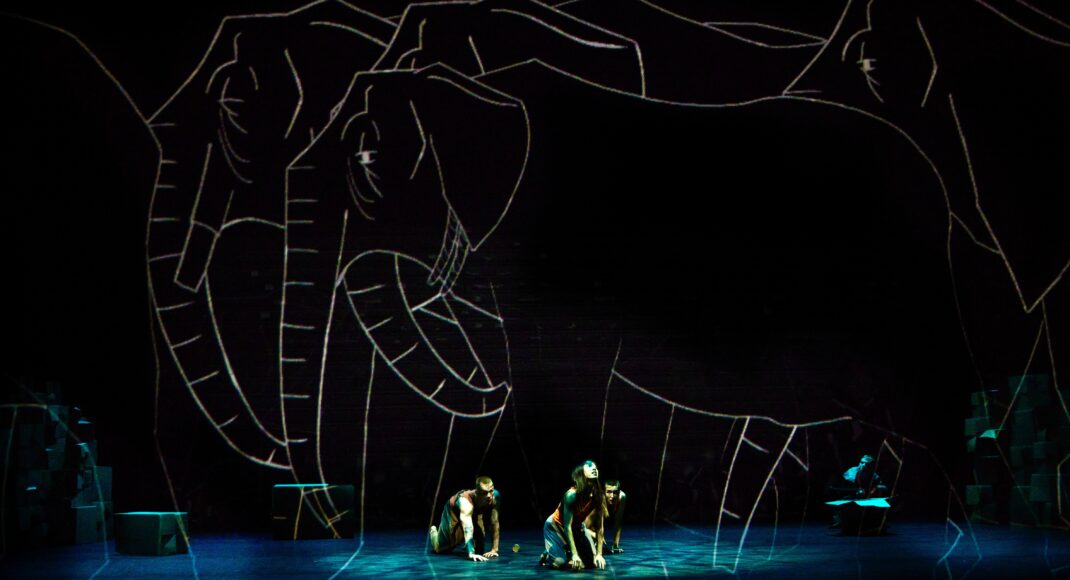

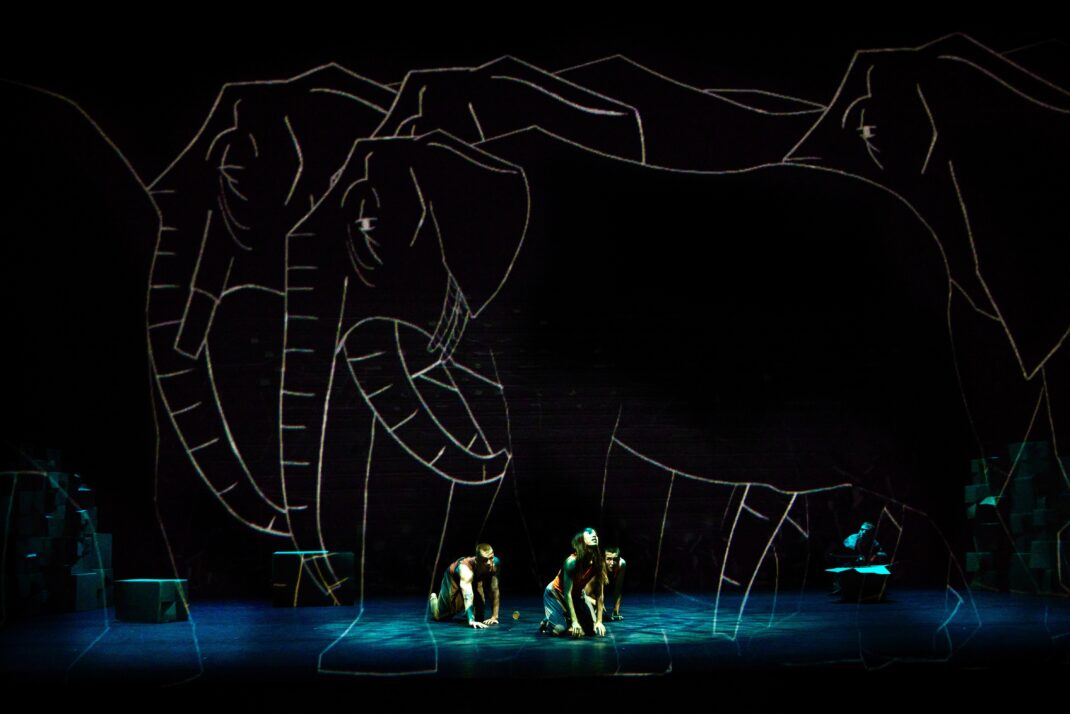

The stage is mostly a launching pad for take-off from gravity, with high-flying spinning aerialists and moving sculptures that evoke time past and time future in a range of astonishing ways.

There’s a striking opening image—backlit figures wired into a ground control centre, they’re there then they’re not—what’s real and what’s virtual? what’s human and what’s AI? who are you and who are you sitting next to?

Five ‘movement and dance specialists’ Brydie Colquhoun, Anu Khapung, Jemima Smith, Aleeya McFadyen-Rew and Nadiyah Akbar, perform dance sequences (still on the ground) of electric staccato movement, as though thoughts are being cancelled before they can be completed, lending urgency and frustration. The ‘aerialist specialists’ are Imogen Stone, Katelyn Reed, Rosita Hendry and Ellyce Bisson. A human standing inside a circle always evokes Leonardo da Vinci’s Vetruvian Man, one of my favourite images of all time. Here that’s a Woman, and her airborne spinning dance within the hoop is something to behold. An impressive singing violinist, Anita Clark, is live and also reflected onto high angled screens that shape-shift before our eyes.

Stunning lighting design offers many a trompe l’oeil that spills the work up into the flies, into the auditorium and the royal boxes, then searches out the audience with waves of blinding light. The stage becomes a sea of mist in which the performers hide, and finally disappear in a devastatingly uncompromising finale.

The work lasts less than a hour, and is described as ‘a meditation on what lies beyond’. It’s the work of Malia Johnston as director/producer, Rowan Pierce as stage and lighting director, Jenny Ritchie as aerial choreographer and costume designer, and composition by Eden Mulholland. You could have called it millennial twenty-five years ago, let’s call it apocalyptic now. Over and again I found echoes from Major Tom—Take your protein pills and put your helmet on … Commencing countdown, engines on … Check ignition and may God’s love be with you … Now it’s time to leave the capsule if you dare … I’m stepping through the door And I’m floating in a most peculiar way … And the stars look very different today … Though I’m past one hundred thousand miles … I’m feeling very still … And I think my spaceship knows which way to go… Tell my wife I love her very much she knows Your circuit’s dead, there’s something wrong. Far above the Moon Planet Earth is blue And there’s nothing I can do.

I then thought of Yuri Gagarin, who after he returned to the ship, albeit late, from the first ever space walk , said ‘I felt as though I had been dancing’.

You can probably tell that the various sensory stimuli of the show, the stunning ‘smoke and mirrors’ that worked without a hitch, invite a high kinaesthetic response in us. We have been warned several times of the haze, strobe, and bright light spill, and such goods were delivered in no small measure. The trouble with that is—as with the road sign ‘Beware of falling rocks’—there’s not a lot you can do about it once you’re on the road. You can always stay home of course—but I wouldn’t have missed the show for the world.

I just close my eyes during strobes, and hold up the programme sheet to block out painfully bright lights (as do a number of the audience around me, even though none of us wants to miss the rest of the imagery). Those breaks in turn mean we are made aware of ourselves watching the show, rather than being totally transported by it, even though we are that too.

You get the feeling there will be more shows from this talented team. I challenge them to find a way of lighting the show to ilIuminate their ideas without trapping us in the headlights. They’ve proved they can do almost anything, so of course they can do this too.

Jennifer Shennan, 15 March 2024

Images: © Andi Crown Photography