29 October 2020, Opera House, Wellington

reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

This is a long-awaited season since the Company’s program, Venus Rising, had to be cancelled due to the Covid situation earlier this year. That had offered an interesting quartet of works, which we could hope to still see at some future date.

The Sleeping Beauty is a major undertaking for any ballet company, demanding high technical skills from a large cast of soloists. Those we saw perform on opening night were all equal to the challenges and danced with much aplomb, carried by the quality of the Tchaikovsky composition, a masterpiece of instrumental wonder, with Hamish McKeich conducting Orchestra Wellington. My seat allowed a view into the orchestra pit which was an extra thrill since there’s a whole other ‘ballet’ of tension, movement, drama and passion going on there.

2018 was the bicentenary of the birth of Marius Petipa, choreographer of this and other iconic ballets from 19th century Russia. That has occasioned new biographies as well as re-worked productions of his ballets, with the recent version by Alexei Ratmansky for American Ballet Theatre winning widespread acclaim for its historical aesthetic coupled with contemporary sensibility. (It is worth looking into The New Yorkers of 1 & 8 June 2016 for Joan Acocella’s brilliant appraisal of the Ratmansky production and style, illustrating how a ballet classic can combine the best of old, though that takes both research and vision). Disney’s Maleficent from 2014 offers another take on who is in charge of evil in the world, updating his 1959 animation classic.

It is always the choices of style and setting, design and drama that, dancing aside, carries a production’s conviction in the passage of time from a christening to a 16th birthday to a sleeping spell of 100 years, to a dénouement and a wedding. This production, originally planned by Danielle Rowe, was instead here staged by Artistic Director Patricia Barker, with Clytie Campbell, Laura McQueen Schultz and Nicholas Schultz, and Michael Auer as dramaturg. With five different credits for various aspects of design, they took a generalised fairystory line, concentrating on light and bright pastel colours for the good, to contrast with the dark and shadowy world of evil.

It was a nice touch to have a poetic verse of the storyline projected onto the screen at the beginning of each ‘chapter’ but the design of set and costumes for the Court of the Rose seemed lightweight rather than royal. The courtiers were reserved in personality and confidence, yet overdressed in costume detail, rather than majestic as befits the mighty orchestral score. Only Loughlan Prior as the addled nervous M.C., (whose initial mistake was to leave Carabosse off the guest list, thus causing all the mayhem) brought caricature and comedy to the play, though the courtiers seemed unwilling to respond in character.

The already-long ballet incorporated several groups of small children—page boys and court attendants. Charming as they were, they seemed more reminiscent of The Nutcracker than this classic which has an important story with a moral thrust in the forces of good versus evil. The King and Queen stood stiff and passionless with gestures portraying this or that but little in the way of emotion at their impending tragedy—and the seating of them and their baby directly upstage of all the court action effectively disappeared them from the scene as they sat behind all the dancing that followed.

Each of the good fairies performed their brief variations with technical flair and aplomb—Generosity by Ana Gallardo Lobaina, Honesty by Lara Flannery, Serenity by Caroline Wiley, Joy by Cadence Barrack, Curiosity by Madeleine Graham and Clarity by Katherine Skelton. (It is impressive to note that four different castings of Aurora are planned over the season. Skelton will be one of them and her delicate precision should carry the role well). Sara Garbowski as the Lilac Fairy offered particular warmth in the portrayal of her promise to save the day. My young companions were impressed at the Aurora Borealis lighting effects—‘Hey, that’s where the baby’s name comes from.’ they whispered in delighted recognition.

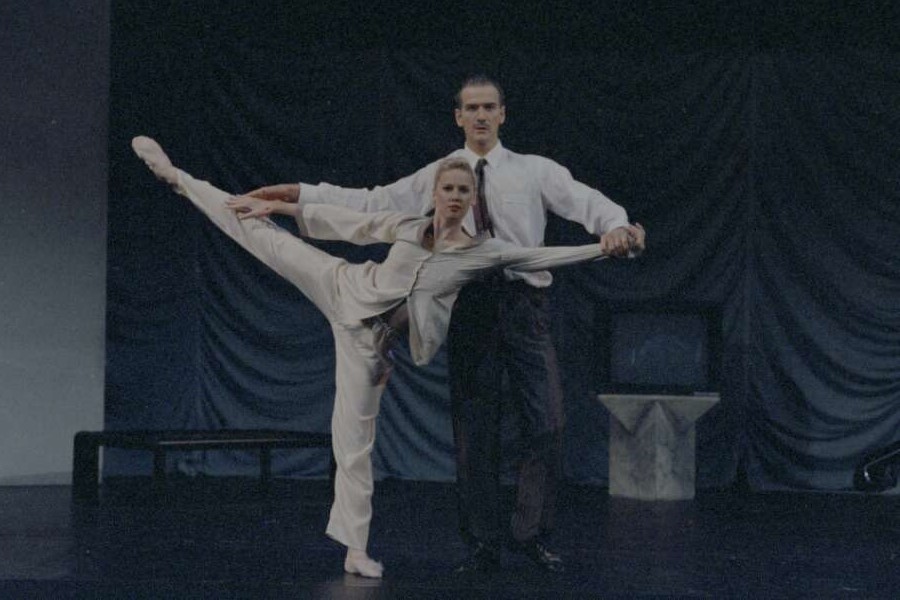

Kate Kadow as Princess Aurora danced radiantly and with an assured technique. Kirby Selchow as Carabosse took her role with relish, conveying macabre delight in wreaking havoc and trouble. Disguising her sidekick Morfran, Paul Mathews, to attend as one of the four suitors to the Princess Aurora on her 16th birthday was a clever ruse to introduce the dreaded spindle disguised as a black rose.

[Intermission. Some day a production might use the auditorium and foyer to help convey the passage of 100 years? That always seems too long a time for a production to ignore].

In Chapter Three, ‘The Hunt Picnic’ brought a group from a faraway court in Lithuania with a lonely Prince ready for a challenge, so the Lilac Fairy showed him the way to wake the sleeping kingdom. The Prince’s name is Laurynas Vėjalis—whoops, that’s the dancer’s name but I’ll use it for the character too since he was immediately apparent as one and the same. From his first entrance, there was the lyricism, strength, nobility and grace one always hopes for in a Principal dancer. Even while standing still, he conveyed those—then his dancing combined agility and strength with musical cadencing that flooded me with joy. This ability to merge the preparation for, together with delivery of, bravura steps into nonchalant movement, is the true heritage of baroque noble dancing, whence the original fairytale hails.

Vėjalis’ strength and speed of allegro movements of his legs and feet, with a simultaneous bone-creaming adagio quality of arm, head and épaulement movements, all without the slightest suggestion of effort or concentration, is a rare natural talent, in the line of Poul Gnatt, Jon Trimmer, Martin James, Ou Lu, Qi Huan, Kohei Iwamoto, Abigail Boyle, proud legacy of this company. It is good, as always, to see the printed program full of content (the work of Susannah Lees-Jeffries) acknowledging the Company’s previous productions.

In the variations from the guests at the wedding—The White Cat by Leonora Voigtlander, and Puss in Boots by Joshua Guillemot-Rodgerson were suitably coquettish, the Bluebirds by Katherine Minor and Kihiro Kusukami in striking flight, Little Red Riding Hood and The Wolf by Georgia Baxter and Jack Lennon bringing character to the scene.

So, all told, a big ballet to big music—though with design of both set and costume in the first two acts less authoritative than might have been. The dancing was stronger and more accomplished than the sense of theatre throughout, where the timing of action needed attention—until along came a Prince who changed all that. I’ll aim to catch the last performance of the tour and see if the production has travelled well, which I’m sure it will.

Jennifer Shennan, 31 October 2020

Featured image: Laurynas Vėjalis as the Prince and Kate Kadow as Princess Aurora in Royal New Zealand Ballet’s production of The Sleeping Beauty. Wellington 2020. Photo: © Stephen A’Court.