reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

24 -27 July 2019. Circa Theatre, Wellington

Suppose somebody took a stem of orchids, choreographed them into women and tossed their experiences, emotions and memories deep into a seamlessly danced stream of consciousness that we might peer into and look for reflections from the depths. Somebody did.

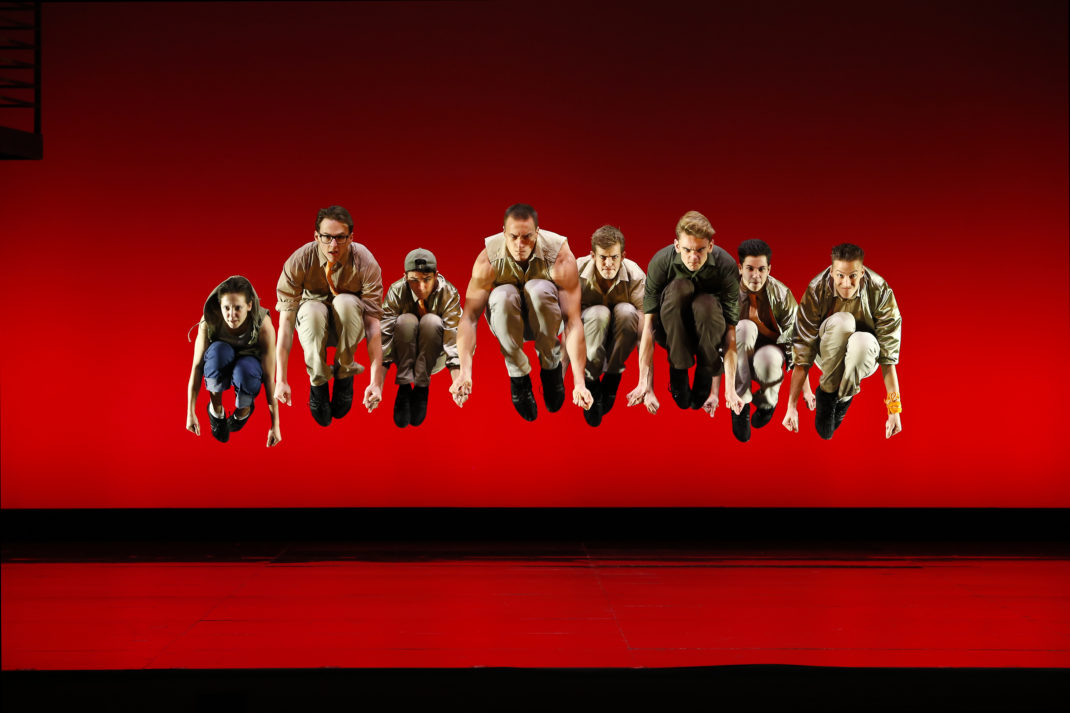

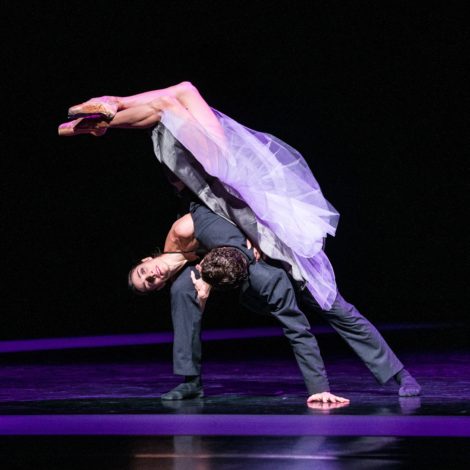

Orchids, choreographed by Sarah Foster-Sproull, is a continuously flowing hour-long dance performed by a cast of seven—six adult women (Katie Burton, Joanne Hobern, Tori Manley-Tapu, Rose Philpott, Marianne Schultz and Jahra Wasasala) of contrasting age and physique, representing us all in the complexity of light and shade in our experiences. In a choreographic masterstroke, a young girl (Ivy Foster, the choreographer’s daughter), serenely evoked our past as a child, and our hope for a future.

The work, ‘an allegory for the dark and light masks of the female psyche’, presents emotions and states of being, rather than storylines with cadence. That openness of texture invites the audience to recognise, interpret, contemplate, empathise, sympathise with and wonder at the undercurrents of meaning in the imaginative movement imagery.

There’s a sculptural quality to the torsos, and much use is made of Sproull’s hallmark hand gestures that seem like a celestial signing of some unspoken speech, a pointing finger that suggests a location or an event, but also asks a question, leaving it unanswered. These motifs always remind me of the account I once read of a 116 year old Japanese woman lying in her bed, patiently awaiting her moment of departure, and performing for her family gathered around ‘her second-to-favourite hand dance.’ (One can only wonder how many hand dances she knew, and what she was saving her favourite one for…perhaps for the afterlife?)

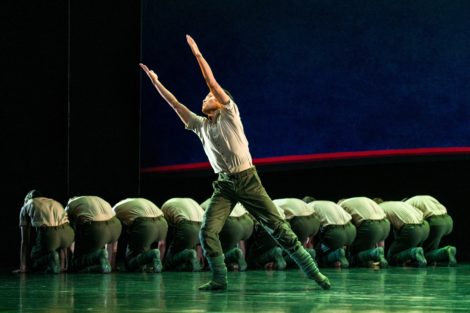

The sequence in Orchids has episodes of solo, duo and larger groupings that suggest woman alone, mother and daughter, sister, friend, rival, confidant, devotee. Much of the movement reflects individuals’ personal experiences with strong emotional force and sometimes surprising dynamic attack, but there are also hints of wider cultural resonance in reference to various female deities or spiritual forces. I believe I recognised one of those to come from Indian Hindu mythology—with Shakti, the goddess of many aspects including the strength of a male capable of stamping out underfoot the demon devil of ignorance.

Music composed by Eden Mulholland had percussive clarity that helped shape the work, and was at one point used as accompaniment, a pluck and two strums, for what suggested a Portuguese fado song about to be danced, but then morphed into more sensuous strings for an all-female Zorba’s dance. A most striking image was the ray of the performers’ fingers shaped like a halo round the face of young Ivy Foster which resonated as the Virgin Mary of Guadalupe, a beacon of hope so desperately believed in by millions of Mexican pilgrims.

The dance follows you home to study the orchids flowering in a pot on your window ledge, to read their folds of petals, their crevices of secrets, their shadows that hide hurt on the underside, beneath the hope that shines light on the upside.

Jennifer Shennan, 26 July 2019

Featured image: Ivy Foster as the Child in Orchids. Foster Dance Group, 2019. Photo: © Jocelen Janon