9 September 2022. QL2 Theatre, Gorman Arts Centre, Canberra

The title of this work may give the impression that is about violence, abusive content, or any other of the somewhat damaging notions that are contained in the more common, singular phrase ’explicit content’. This was not the case with Explicit Contents, the dance work, as I understood it, although a certain sensuality was made clear at various times. Made on two dancers, Ivey Wawn and David Huggins, by the Sydney-based choreographer Rhiannon Newton, the work for me was calming, contemplative and mesmerising, at least for most of the time and in certain respects.

The work had begun as we entered the performing space with Wawn and Huggins moving to and fro with Newton’s quite simple but nicely performed choreography—introductory moments. The main body of the work began shortly afterwards when the space was plunged into darkness and we watched the dancers moving, occasionally and subtly, while stretched out on the floor, upstage. There were quite long periods of stillness and the darkness made it hard to make out what was happening. In some respects though it reminded me of the Merce Cunningham concept of ‘body time’ as without any obvious score at this stage (the noise we heard was from cars driving up and down the road outside the Arts Centre), the two dancers were aware of each other and seemed mostly to be working in unison with slight, individual variations.

As this dark and slowly moving section continued, it began to be interrupted by drops of water falling on the floor (lit so they were visible as they landed). From there the work unfolded in a number of episodes, to a sound score by Peter Lenaerts and in which the two dancers engaged in a series of activities. They sat on the ground in front of us and ate a piece of fruit, Wawn had a passionfruit, Huggins a mango. They picked up a glass bowl half filled with water and manipulated the water level before balancing it on their bodies. In an unexpected moment they tipped the water on the floor and sat down and swirled around in that seated position. Another earlier episode had the dancers taking geometrical-style poses, sometimes mirroring each other, at other times taking separate stances

Choreographically, however, the work was not really outstanding. While Wawn and Huggins reacted beautifully to Newton’s style, they hadn’t really been given hugely challenging movement. It was more about a concept on which Newton had based the work, ‘how bodies are are not separate from but inextricably connected to their environments’. Although I found the work calming and mesmerising, I think this feeling came from non-choreographic aspects of the work, aspects that were visually interesting rather than choreographically challenging—water dripping to the floor, eating fruit, balancing bowls of water on the body, and the incredible lighting from Karen Norris, especially those moments when her lighting allowed the dancers bodies to be reflected mirror-like onto the floor.

I recall a colleague saying once ‘Dance is a visual art form’, to which another colleague replied, ‘No it’s not, it’s much more than that.’ This is the first work from Newton that I have seen. I look forward to seeing more and will be curious to see how/if she balances the various aspects that make a work a dance one. The balance was not convincing in Explicit Contents.

Michelle Potter, 10 September 2022

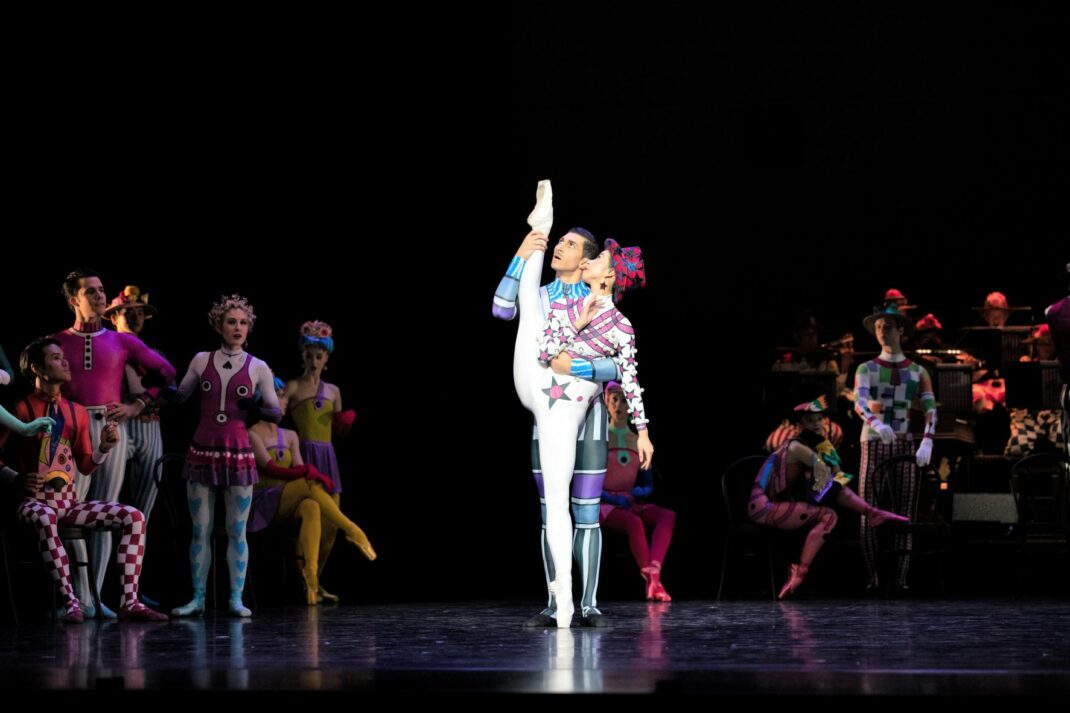

Featured image: Ivey Wawn and David Huggins in a scene from Explicit Contents. Photo: © Gregory Lorenzutti