- ACT Arts Awards 2017

The ACT Arts Awards for 2017, an initiative of the Canberra Critics’ Circle, were announced in Canberra on 27 November. The major award, ACT Artist of the Year, sponsored by the weekly newspaper City News, went to dancer, choreographer and director, Liz Lea. This award is the subject of a separate post at this link.

In the wider category, where awards go to ACT-based artists across the various performing arts genres, the visual arts and literature, two dance awards were given.

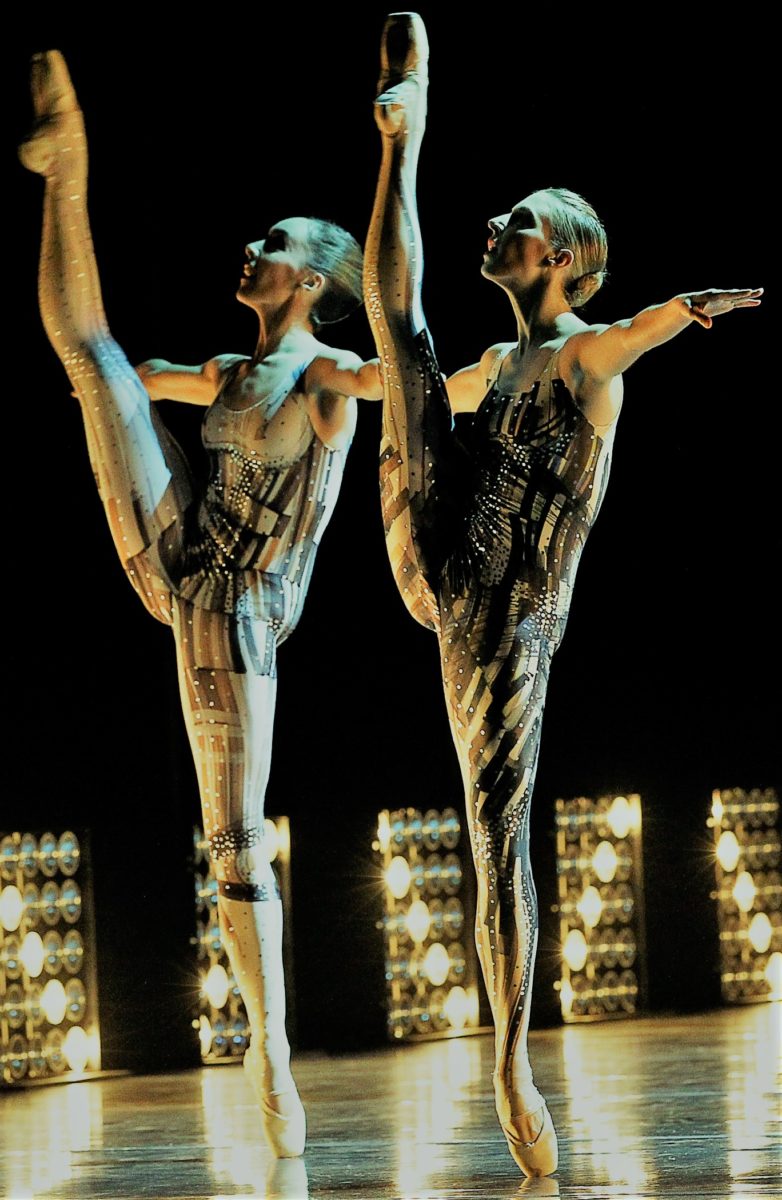

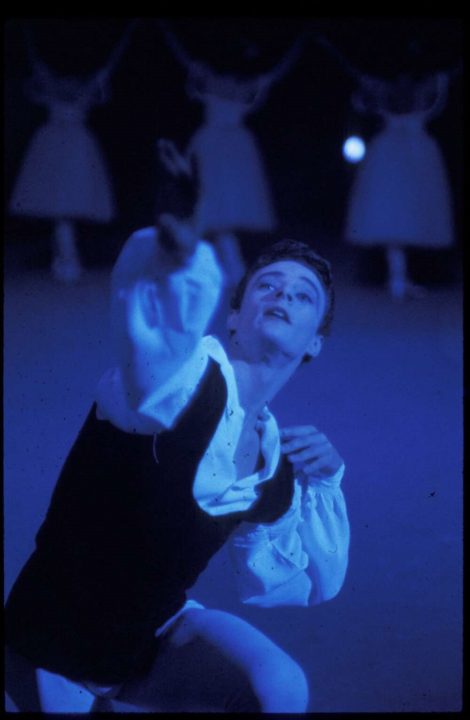

- Photographer Lorna Sim was awarded ‘For her outstanding contribution to dance in the ACT through her photography of dance, and her 2017 exhibition of dance photographs Enigma.’ One of her remarkable images from Enigma is the featured image on this post.

- Katie Senior and Liz Lea shared an award ‘For their moving and elegiac dance work That extra ‘some created in celebration of a remarkable friendship.’ For a review of this work follow this link.

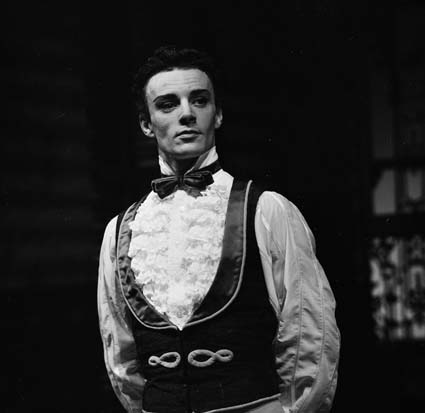

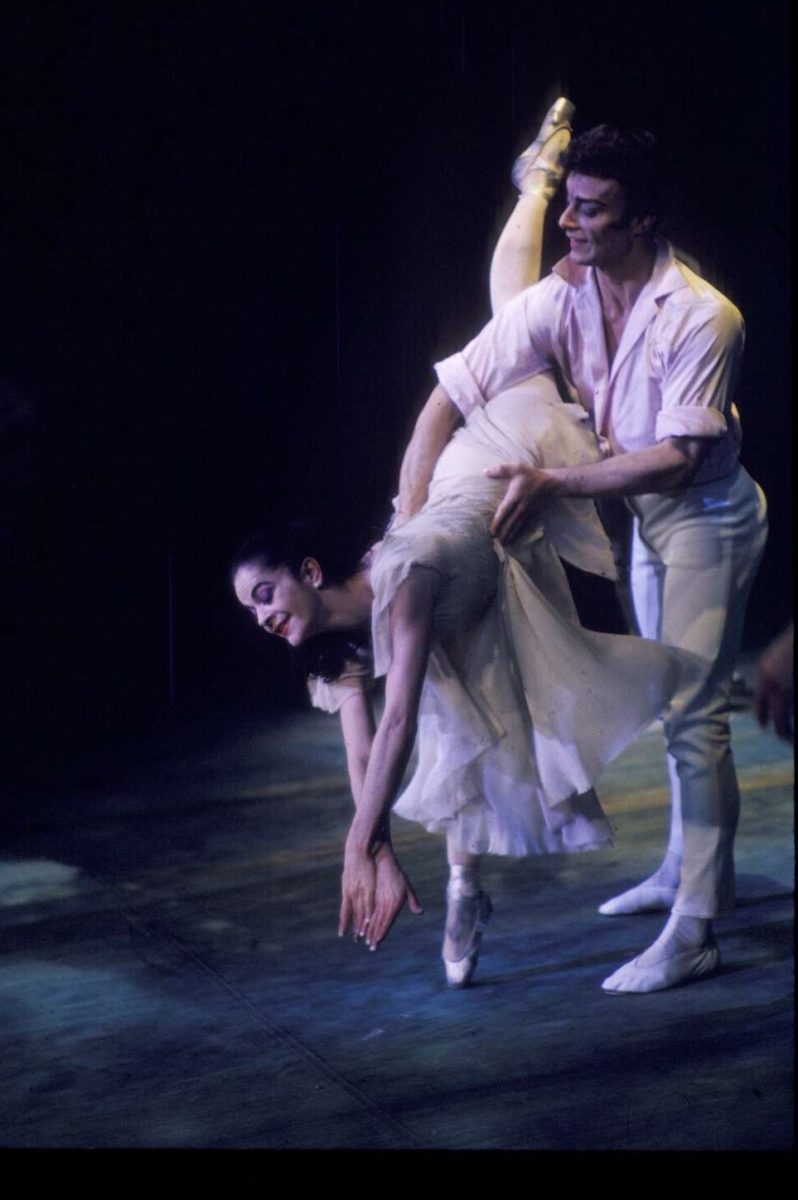

- David Vaughan (1924–2017)

I was saddened to hear of the death in October in New York of British-born dance archivist, historian and critic David Vaughan. I first met Vaughan in the early 1990s when I was doing research for my doctoral thesis, which concerned Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns and their collaborations with Merce Cunningham and John Cage. Vaughan was the generous archivist of the Cunningham Foundation. I met up with him several times after that and was proud to be a co-curator with him and Barbara Cohen-Stratyner of the exhibition INVENTION. Merce Cunningham and Collaborators at the Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, New York, in 2007.

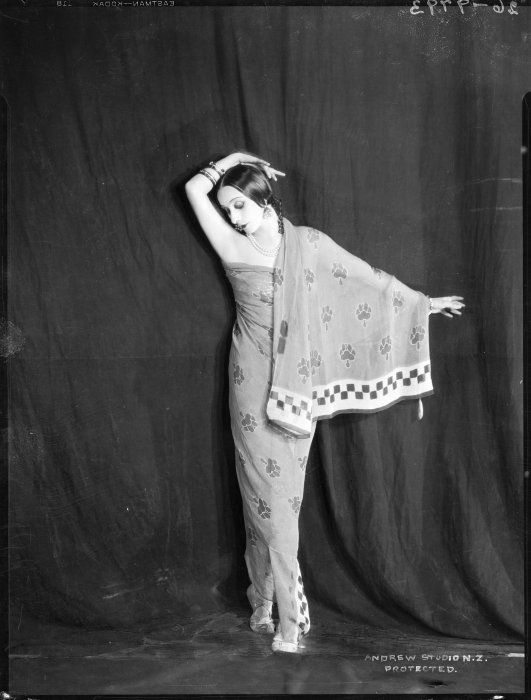

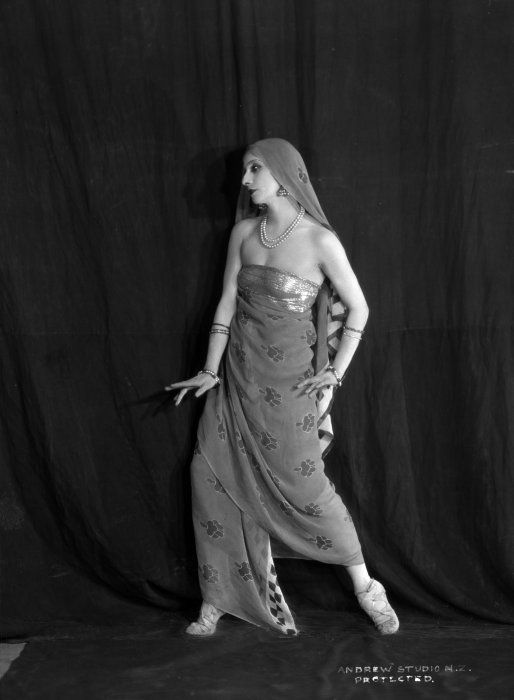

David Vaughan’s writing has been widely published in a variety of formats, but the two works that stand out in my mind are his spendid work on the ballets of Frederick Ashton, originally published in 1977 and revised in 1999— Frederick Ashton and his ballets. Revised edition (London: Dance Books, 1999)—and his equally impressive Merce Cunningham. Fifty years (New York: Aperture, 1997), and its accompanying app.

- Degas from Scotland in London

Just recently I saw a small, but quite beautiful show called Drawn in colour. Degas from the Burrell at the National Gallery in London. The works by Degas came mostly from the Burrell Collection, Glasgow, although some items, designed to expand the exhibition, came from elsewhere. The items from the Burrell Collection have rarely travelled before, and most were new to me. I especially liked the one I have chosen as illustration, The green ballet skirt, for the gorgeous way Degas has painted the skirt being so carefully treated by the dancer before (I am assuming) she goes on stage.

The Degas paintings, drawings and sculptures on display in this show are part of an extensive collection of art works given to the city of Glasgow by a wealthy Glaswegian shipping merchant, Sir William Burrell. The exhibition runs from 20 September 2017 to 7 May 2018. More at this link.

- Press for November 2017

‘Moving towards inclusion.’ Preview of the dance component of the Detonate program at Belconnen Arts Centre. Panorama (The Canberra Times), 25 November 2017, pp. 10–11. Online version

Michelle Potter, 30 November 2017

- Late addition (2 December 2017)

I have just received a link to the latest edition of the remarkable Dance Books catalogue and, rather than wait until my January dance diary, I am including it here as a late addition—a source of Christmas gifts? UPDATE Link no longer available)

Featured image: Eliza Sanders from the Enigma series. Photo: © Lorna Sim