29 June 2017. Drama Theatre, Sydney Opera House

Bennelong, Bangarra Dance Theatre’s most recent work, may well be the company’s most ambitious production to date. Yet in saying that, I can’t help feeling that it may also be its most powerful, its most emotive, and its most compelling show ever.

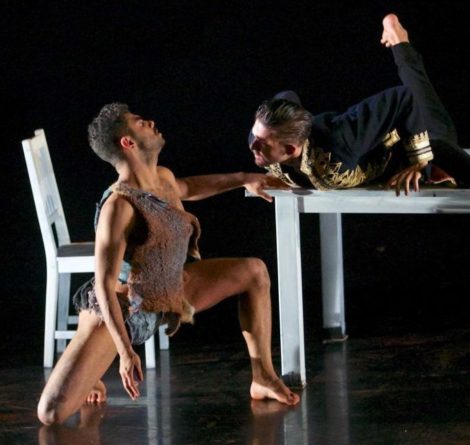

Stephen Page, as choreographer and creative storyteller, has taken the life of Wongal man, Woollarawarre Bennelong, as a starting point: Bennelong the man feted in many ways in early colonial society, and yet denigrated in so many other ways by that same society. Page presents a series of episodes in Bennelong’s life from birth to death. In those episodes we experience a range of emotions from horror in ‘Onslaught’ as large sections of the indigenous population are wiped out by an epidemic of smallpox, to a weird kind of fascination in ‘Crown’ when we watch Bennelong interacting with British high society after he arrives in London.

There is a strength too in how Page has ordered (or selected) the events. ‘Onslaught’ for example, follows ‘Responding’ in which the indigenous population is ‘assimilated’ by wearing Western clothing. We can’t help but make the connection between the arrival of the colonials and the outbreak of a Western disease. And following ‘Crown’ comes ‘Repatriation’ when we watch another emotionally difficult scene referring to ongoing efforts to repatriate bones and spirits of those who died in London (or perhaps even those whose bones and spirits were taken to London as ‘specimens’). It is tough but compelling watching.

The score for Bennelong was largely composed and performed by Steve Francis, but it also makes many references to the Bennelong story with snippets of music and song from elsewhere—the strains of Rule Britannia at one stage, a rousing sailor song as Bennelong is transported to London by ship, and some Haydn as Bennelong attends a ball with British society. The dancers and others, including dramaturg Alana Valentine and composer Matthew Doyle, have also been recorded speaking and singing and these recordings have been integrated into the score. It is absolutely spellbinding sound.

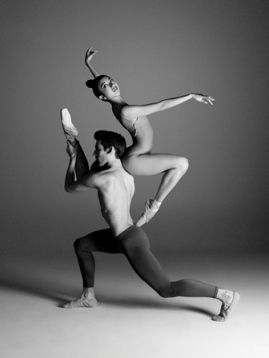

As is usual in a Bangarra production the visual elements were outstanding. I especially enjoyed Jennifer Irwins’s costumes, which were suggestive of various eras in indigenous and colonial society, from pre-colonial times to the present, without always being exact replicas.

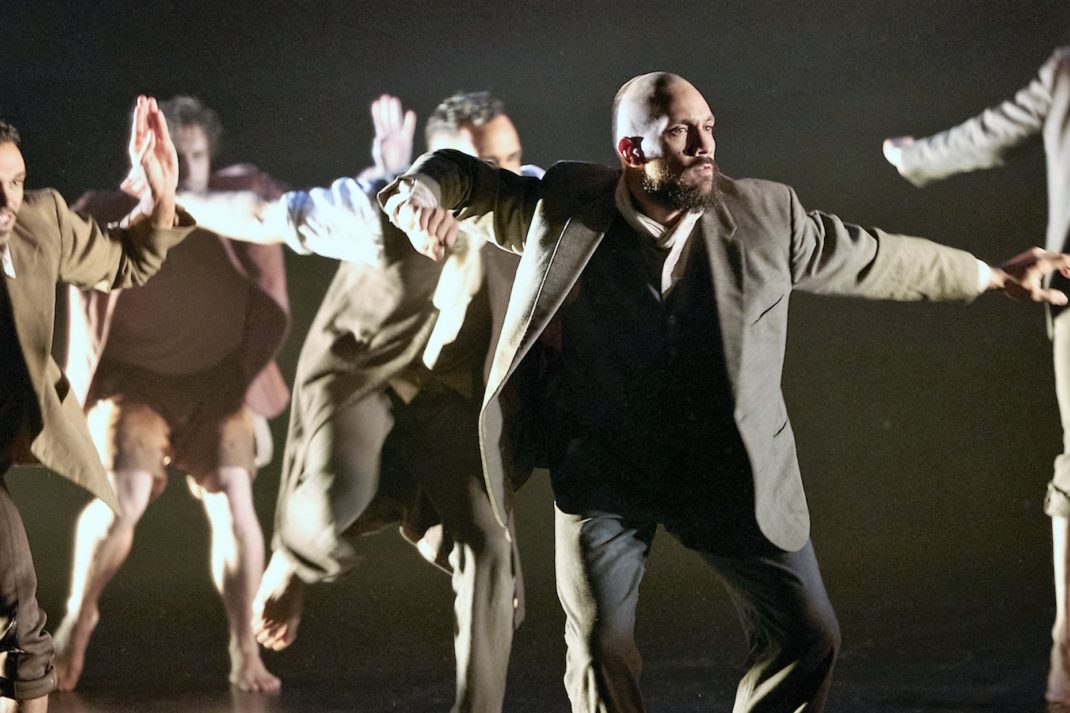

The entire company was in exceptional form, with Elma Kris in a variety of roles as a keeper of indigenous knowledge, and Daniel Riley as Governor Phillip, giving particularly strong performances. But it was Beau Dean Riley Smith as Bennelong who was the powerful presence throughout. In addition to his solo work, it was impossible not to notice and be impressed by him in group sections and in his various encounters with others throughout the piece.

But it was in the final section, ‘1813/People of the Land’, that he totally captured the essence of what was at the heart Page’s conception of the character of Bennelong, a man trapped between two worlds and seeming to belong fully to neither. As he struggled physically and verbally to understand his position, and as he found himself slowly being encased in a prison (or mausoleum—Bennelong died in 1813), Smith was a forlorn and tortured figure. It was thrilling theatre. And that concrete-looking structure that was slowly built around him, and that eventually blocked him out from audience view entirely, was another powerful visual element. As the curtain fell, the prison structure carried a projection of a well-known colonial portrait of Bennelong and it seemed to represent the disappearance of indigenous culture at the hands of the colonial faction.

Bennelong was a truly dramatic and compelling piece of dance theatre. It deserved every moment of the huge ovation it received as it concluded. We all stood.

Michelle Potter, 1 July 2017

Featured image: Beau Dean Riley Smith in Bennelong. Bangarra Dance Theatre, 2017. Photo: © Daniel Boud