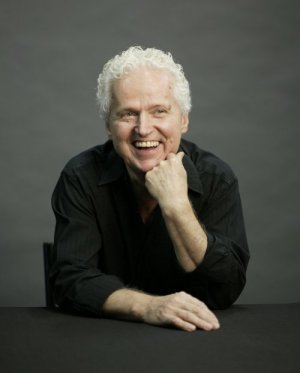

- Vale Andris Toppe

I was saddened to hear of the death of Andris Toppe whose contribution to the world of dance in Australia has been extraordinarily varied. The most lasting image I have of him in performance is as one of Clara’s Russian émigré friends in Graeme Murphy’s Nutcracker: the story of Clara where his portrayal was strong and individualistic. Just a few weeks ago, too, I had an email from him saying how much he enjoyed reading my biography of Dame Margaret Scott. At the time I had no idea he was so ill but now I am hugely pleased that he derived pleasure from the book in his final weeks of life.

For a biography and gallery of images see Andris’ website.

Andris Toppe: born 16 May 1945, died 20 February 2016

- Janet. A Silent Ballet Film

In February I was unexpectedly contacted by film maker Adam E Stone who sent me a link to a work he directed called Janet. A Silent Ballet Film. The Janet of the title is Janet Collins, an African-American dancer who is remembered as the first black dancer to dance full-time with a major dance company, in this case the Metropolitan Opera Ballet, which Collins joined in 1951.

Janet is moving in the way it conveys a political message, and in the complexity of the message it sets out to convey. It is interesting to speculate on why Stone chose to use the medium of silent film (the silencing of so-called minority cultures?), and also to speculate on the role the paintings of Degas play (some well known Degas ballet images are brought to life throughout the film). The dancer who plays Janet is Kiara Felder from Atlanta Ballet and she is a joy to watch.

- Steven McRae in Frederick Ashton’s Rhapsody

I have always found Steven McRae, Australian-born principal with Britain’s Royal Ballet, a little polite on those occasions when I have seen him live in performance. There has always seemed to be something he is holding back in his dancing, in spite of a very sound technique. Well, I now have seen another side of him in the Royal Ballet’s recently-screened film of an Ashton program consisting of Rhapsody and The Two Pigeons. As the leading male dancer (partnering Natalia Osipova) in Rhapsody, a work Ashton made in 1980, McRae was technically outstanding, handling the intricacies and speed of the Ashton choreography with apparent ease. He also gave his role a strength of character allowing us to imagine a storyline, if we so chose. Great performance. Terrific immersion in the role.

- Site news

I published my first post on this site in June 2009, almost seven years ago. So much has changed in web design and development since then and I am pleased to announce that the design team at Racket is working on a new look for this site. Stay tuned.

- Press for February

‘Dancing for survival.’ Preview of Indigenous dance programs at the National Film and Sound Archive. The Canberra Times, Panorama 6 February 2016, pp. 8–9. Online version.

Michelle Potter, 29 February 2016