In Canberra

Below is a slightly expanded version of my year-ender for The Canberra Times published as ‘State of dance impressive and varied’ on 24 December 2018. I should add that The Canberra Times‘ arts writers/reviewers are asked to choose five productions only for their year-ender story.

Looking back at 2018 I find, thankfully, that I don’t have to complain too much about the state of dance in the ACT. In 2018, in addition to work from a variety of local companies and project-based groups, dance audiences in Canberra were treated to visits from the Australian Ballet, the Australian Ballet School, Australian Dance Theatre, Bangarra Dance Theatre, the Farm and Sydney Dance Company. Most performances were in traditional venues, but one or two were site specific (notably Australian Dance Party’s production of Energeia performed at the Mount Majura Solar Farm) and, in addition, the National Portrait Gallery and the National Gallery of Australia offered their venues for dance performances. Beyond performance, it was exceptional news that Rafael Bonachela, artistic director of Sydney Dance Company, had agreed to become a patron of QL2 Dance, Canberra’s youth organisation. In a casual conversation with me he mentioned that he had always been impressed with those ex-QL2 dancers who had gone on to perform with Sydney Dance Company and also that he regretted that he had not had a strong mentor himself during his early training. Both thoughts fed into his decision to take on the role of patron.

I have arranged my top five events chronologically according to the month in which they were performed.

RED. Liz Lea Productions

In March Liz Lea presented RED, a work that won her a Canberra Critics’ Circle Award later in the year. It was a powerful, courageous, autobiographical work that touched on Lea’s struggle throughout her career with endometriosis. But beyond that it was distinguished by outstanding choreography from four creators, all of whom highlighted Lea’s particular strengths as a dancer. In addition to Lea herself, choreographic input came from Vicki van Hout, Virginia Ferris and Martin del Amo. There was also stunning lighting by Karen Norris; a range of film clips that added context throughout; and strong dramaturgy by Brian Lucas, which gave coherence and clarity to the overall concept. It was a highly theatrical show, which also presented a very human, very moving message.

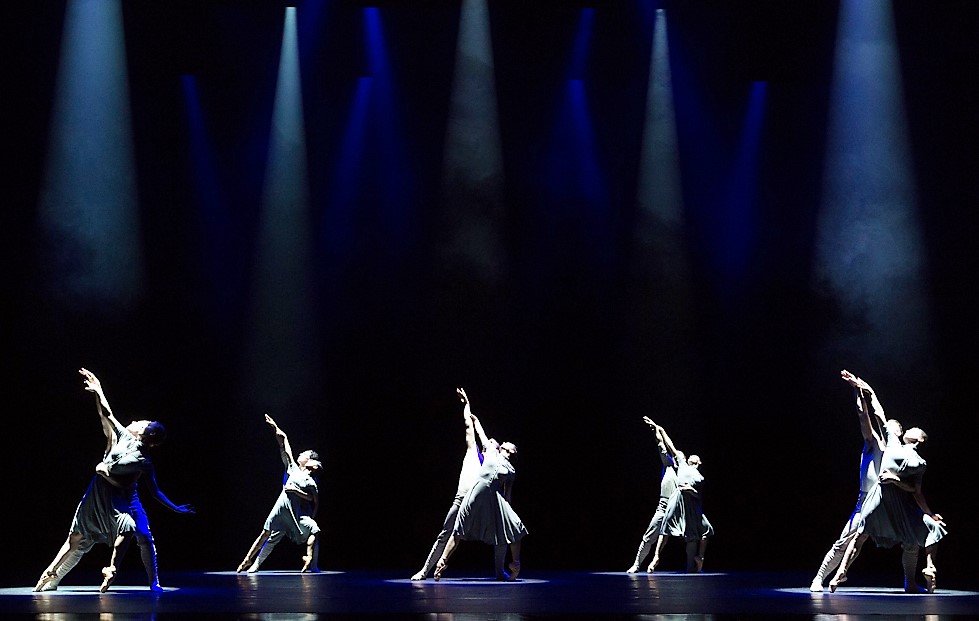

The Beginning of Nature. Australian Dance Theatre

In June Australian Dance Theatre returned to the national capital after an absence of more than a decade. The Beginning of Nature, choreographed by artistic director Garry Stewart, focused on the varied rhythms of nature. It was compelling and engrossing to watch. The dancers seemed to defy gravity at times and their extreme physicality was breathtaking. But the work was also an outstanding example of collaboration between Stewart, his dancers, an indigenous consultant familiar with the almost-extinct Kaurna language of the Adelaide Hills, and composer Brendan Woithe, who created a remarkable score played live onstage by a string quartet.

Cockfight. The Farm

The Farm, featuring performers Gavin Webber and Joshua Thomson, arrived In September with Cockfight. Set in an office situation, and dealing with interpersonal relations within that environment, Cockfight was an exceptional example of physical theatre. Both Webber and Thomson gave riveting performances and the work presented a wide range of ideas and concepts, some filled with psychological drama, others overflowing with humour. It was totally absorbing from beginning to end.

Gavin Webber and Joshua Thomson in Cockfight. Photo: © Darcy Grant

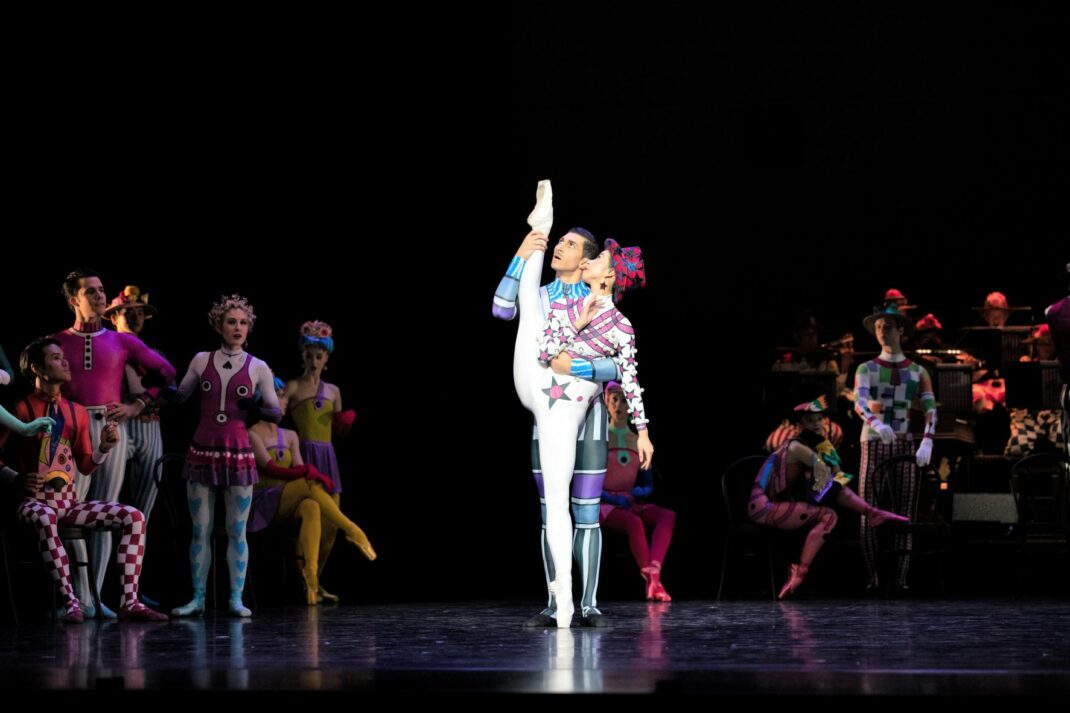

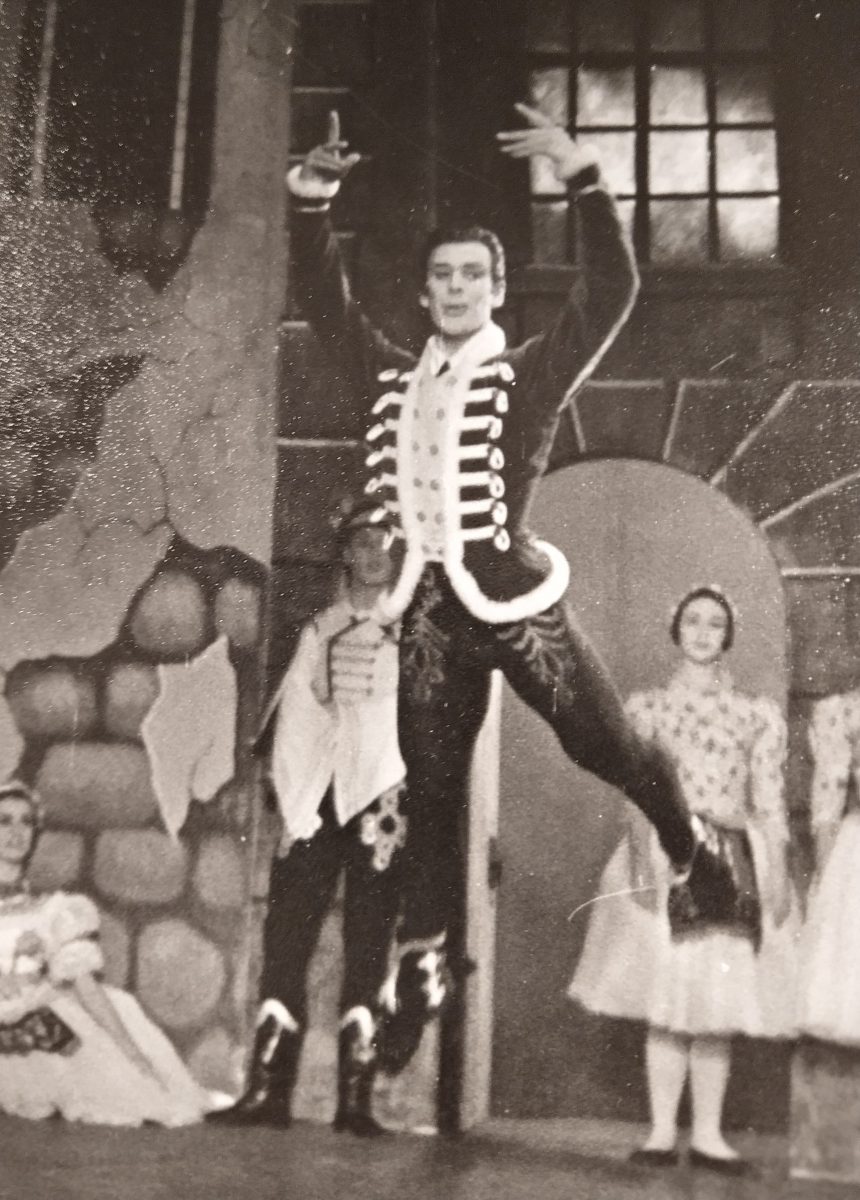

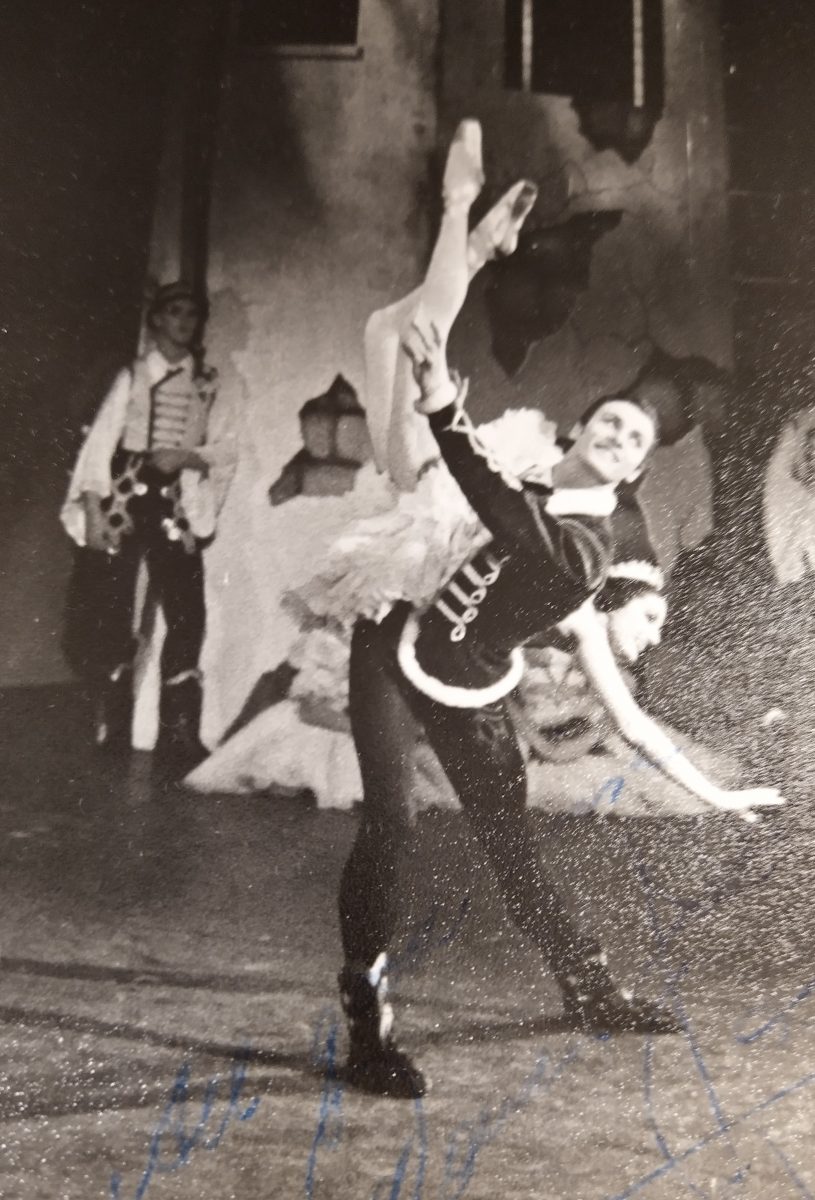

World Superstars of Ballet Gala. Bravissimo Productions

This Canberra-only event early in October showcased a range of outstanding dancers from across the world in a program of solos and duets, mostly from well-known works from the international ballet repertoire. It belongs in the list of my dance picks for 2018 on the one hand because the artists showed us some spectacular dancing. But it also belongs here because Bravissimo Productions (a newly established Canberra-based production company) had the courage to take on the task of defying convention and certain ingrained ideas about Canberra, including the perceived notion that Canberra equals Parliament and the Public Service and little else, and the constant complaints about performing spaces in the city. Bravissimo brought superstars of the ballet world not to Sydney or Melbourne or Brisbane, but to Canberra. The international stars that came were not the worn-out, about-to-retire dancers we so often see here from Russian ballet companies, but stars of today. I hope Bravissimo Productions can keep it up. Canberra is waiting.

MIST. Anca Frankenhaeuser and Kailin Yong

MIST was the standout performance of the year for me. It was one item in Canberra Dance Theatre’s 40th anniversary production Happiness is…, which took the stage in mid October. As a whole, Happiness is… was somewhat uneven in the quality of its choreography and performance, but MIST, listed as a duet in the form of a pas de deux between a dancer and a musician, was simply sensational. And it really was a pas de deux with violinist Kailin Yong moving around the stage, and even lying down at times as he played and improvised, and with dancer Anca Frankenhaeuser involving herself with his playing in a way that I have never seen anywhere before. With choreography by Stephanie Burridge, an ex-Canberran now living in Singapore, it also carried an underlying theme about relationships between people. It was an exceptional concept from Burridge, beautifully realised by Frankenhaeuser and Yong.

I hope we can keep moving forward in Canberra in 2019 with dance that is inclusive and collaborative, and also theatrically and intellectually satisfying. A varied program of dance in 2018 showed us the possibilities.

Beyond Canberra

I had the good fortune to see quite a lot of dance outside of Canberra including in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane as well as outside of Australia in London and, briefly, in Wellington, New Zealand. Leaving London and Wellington aside since I am focusing on dance seen in Australia, the standout show for me was the La Scala production of Don Quixote, staged in Brisbane as part of Queensland’s outstanding initiative, its International Series. Apart from some seriously beautiful dancing, especially from the corps de ballet who seemed to understand perfectly how to move in unison (even in counterpoint) and how to be aware of fellow dancers, I loved that extreme pantomime was left out. As I wrote in my review it was a treat to see a Don Quixote who actually presented himself as a quixotic person rather than a panto character.

I was also intrigued by Greg Horsman’s new take on La Bayadère for Queensland Ballet. Horsman set his version in India during the British occupation. The story was cleverly reimagined and beautifully redesigned by Gary Harris, yet it managed to retain the essence of the narrative and, in fact, the story was quite gripping as it sped along.

But for me the standout production/performance from outside Canberra was Alice Topp’s Aurum for the Australian Ballet and performed in their Verve season in Melbourne. It was filled with emotion from beginning to end, sometimes overwhelmingly so. In one section it had the audience so involved that all we could do was shout and cheer with excitement. Choreographically it was quite startling, moving as it did from surging, swooping movement to a final peaceful, but stunningly realised resolution. A real show-stopper.

May we have more great dance in 2019!

Michelle Potter, 31 December 2018

Featured image: Kailin Yong and Anca Frankenhaeuser in MIST. Photo: © Art Atelier Photography