22 April, 2017, Palais Garnier, Paris

Recently The Times (London) carried a short article entitled ‘Learn language while you wait for web page to load’. It concerned newly developed apps that ‘test you on vocabulary in idle moments, such as when you are connecting to a network or waiting for an instant message.’* The timing of the article was serendipitous. It came to my attention as I was about to see Paris Opera Ballet’s triple bill, Merce Cunningham and William Forsythe. It seemed like it was an update to what Merce Cunningham was interested to explore with his Walkaround Time (1968), the first work on the POB program. I set off for the theatre with even more anticipation than usual. Cunningham truly was ahead of his time I mused.

The title Walkaround Time, according to Cunningham, comes from computer language. ‘You feed the computer information then you have to wait while it digests.’** Cunningham mentions, however, that it isn’t clear whether it is the computer or the user who is doing the walking around, although for him it is clearly the people!

The dancers of POB handled the Cunningham choreography beautifully—staging was by ex-Cunningham dancers Jennifer Goggans and Meg Harper. I admired especially the dancer who took the role originally danced by Carolyn Brown. Many of the artists appearing in this program (at least at the performance I saw) were not high enough up in the POB hierarchy to warrant a photo in the printed program, so I don’t know who she was. In any case, she was exceptional in her ability to display the balance and stillness this role requires at times, but also showed a beautiful fullness to her dancing when moving was part of the choreography. But all the dancers I saw, with their finely honed bodies and inbuilt understanding of shape and space, brought a wonderful quality to the work, showing as they did the clarity of Cunningham’s deceptively simple choreography.

Jasper Johns’ set, which referred to Marcel Duchamp’s dada-ist Large Glass, and David Behrman’s score …for nearly an hour…, set the work firmly within the Cunningham collaborative tradition, highlighting the independence of the collaborative elements. Watching Walkaround Time was a truly evocative and quite exciting experience.

The first of the two works by William Forsythe that made up the rest of the program was Trio. It had some conceptual similarities to the Cunningham piece, even though Forsythe, unlike Cunningham, works within the vocabulary of classical ballet. Trio was a kind of slapstick piece, reminding me a little of something from Cirque du soleil. The dancers came forward pointing out different parts of their body in between dancing and engaging in a kind of rough and tumble physical contact. But, with its stop-start musical accompaniment (a Quartet by Beethoven), and with several sections of dancing being executed in silence, the link back to Cunningham was uncanny.

Herman Schmerman, consists of two parts (made at different times in the 1990s)—a pas de cinq followed by a pas de deux. It probably was the work that showed the dancers of Paris Opera Ballet at their balletic best. The pas de cinq, fast-paced and showy, gave them the opportunity to display speed, intricate beaten work and extended limbs. I especially enjoyed the dancing of Chun Wing Lam. He moved brilliantly, using every part of his body. He twisted, turned, bent all ways, moved so smoothly and fluidly, and looked as though he was having the best time. Wonderful to watch.

The pas de deux, danced by Aurélia Bellett and Aurélien Houette, was a little unusual. In its vocabulary, it had Forsythe’s signature elements of extended limbs, off-centre poses, startling lifts, and the like, scattered throughout the piece. But the communication between the two dancers was not what one might have expected. They were sometimes off-hand with each other, and sometimes they seemed to be in teasing mode. They were a little cheeky and often amusing in the way they related to each other. A bit like life really.

Both the pas de cinq and pas de deux had delightful and surprising endings. As the pas de cinq came to an end, all five dancers disappeared behind a low barrier that stretched across the back of the stage. The accompanying lighting, by Tanji Rühl and Forsythe, was gorgeous and was enhanced by the appearance of two large orange/yellow circles of light on the backcloth as the dancers popped their heads up over the barrier. In a similarly surprising and delightful way, towards the end of the pas de deux both the woman and the man added short, yellow, pleated skirts over their black, close-fitting costumes (costume design by Gianni Versace and Forsythe) and continued the dance with skirts swinging jauntily.

Merce Cunningham and William Forsythe was an inspired program. It was through the vision of Benjamin Millepied, now no longer dance director of POB, that these three works entered the repertoire. Together they made up a program that clearly showed what dance can accomplish in the hands of two exceptional intellects and two inquiring choreographic minds.

Michelle Potter, 24 April 2017

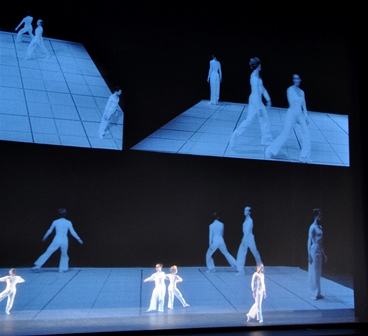

Featured image: Artists of Paris Opera Ballet in Herman Schmerman, 2017. Photo: © Ann Ray/Opéra national de Paris

* The Times (London), 22 April 2017, p. 5

** Quoted in the app Merce Cunningham 65 Years