April is the middle month of Autumn in the southern hemisphere. Spectacular colours abound in nature as dance for 2025 continues, despite a disheartening approach to funding for the art form.

The difficult financial situation that Queensland Ballet is facing, for example, is more than disheartening, although the exact changes that are being made to the company are yet to be fully revealed. To date, Brett Clark, Chair of QB Board, is reported as saying (amongst other remarks on the situation): Over the years, we have worked hard to leverage our base grants from State and Federal Governments and have unapologetically advocated loudly for parity of Federal funding to bring us in line with our peers in New South Wales and Victoria. To date we have been unsuccessful.

In 2025, to ensure our ongoing sustainability, we have made the difficult decision to re-vision our organisation across our Artistic and Business teams which will see us farewell some of our artists and arts workers.

It is also thoroughly frustrating that in the lead-up to the federal election in Australia on 3 May no political party appears to have made any mention of the arts.

- New books

Elizabeth Dalman’s book, Nature moves, was launched in Canberra on 27 April 2025 with a short opening performance from Vivienne Rogis and Peng Hsaio-yin. The performance was followed by a launch speech from Cathy Adamek, executive director of Ausdance ACT.

The performance was danced on a lawn that fronts a particular shopping area in Canberra, and under a large and very old tree—appropriate of course given that Dalman’s book examines dance and nature. When the dance came to an end, the audience simply crossed the road for the launch function, which was held in, and sponsored by, the local bookshop, The Book Cow.

Under the heading ‘Press for April 2025’ (see below) is my short article, which was published in CityNews on 28 April 2025, and which expands a little on how the launch unfolded.

Nature Moves is available from The Book Cow, via this link.

I also discovered, quite accidentally, news about the latest publication by Jill Rivers, whose generosity to reviewers I remember clearly from a period, some years ago now, when she was media director for the Australian Ballet. Her current publication, The Genius of Nijinsky, is an interesting read as Rivers had spent much time speaking to the present-day family of Vaslav Nijinsky. Her presence with, and thoughts about, those family members in a range of situations, sometimes quite personal, are embedded within the story.

The Genius of Nijinsky can be bought via a link to the site Art-full Living.

- David Hallberg at Jacob’s Pillow, 2012

The latest playlist from Jacob’s Pillow has a short clip of David Hallberg, currently artistic director of the Australian Ballet, performing Nacho Duato’s Kaburias. Watch at this link.

Just a year or two prior to the performance at Jacob’s Pillow, I had the pleasure of seeing Hallberg perform solo in New York in the series Kings of the Dance. Read my review here.

- International Dance Day 2025

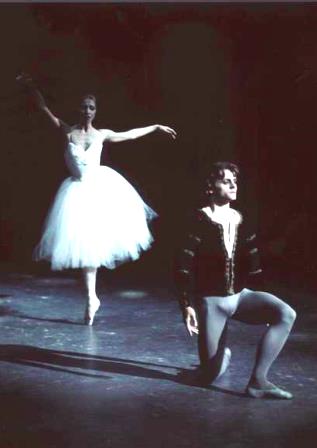

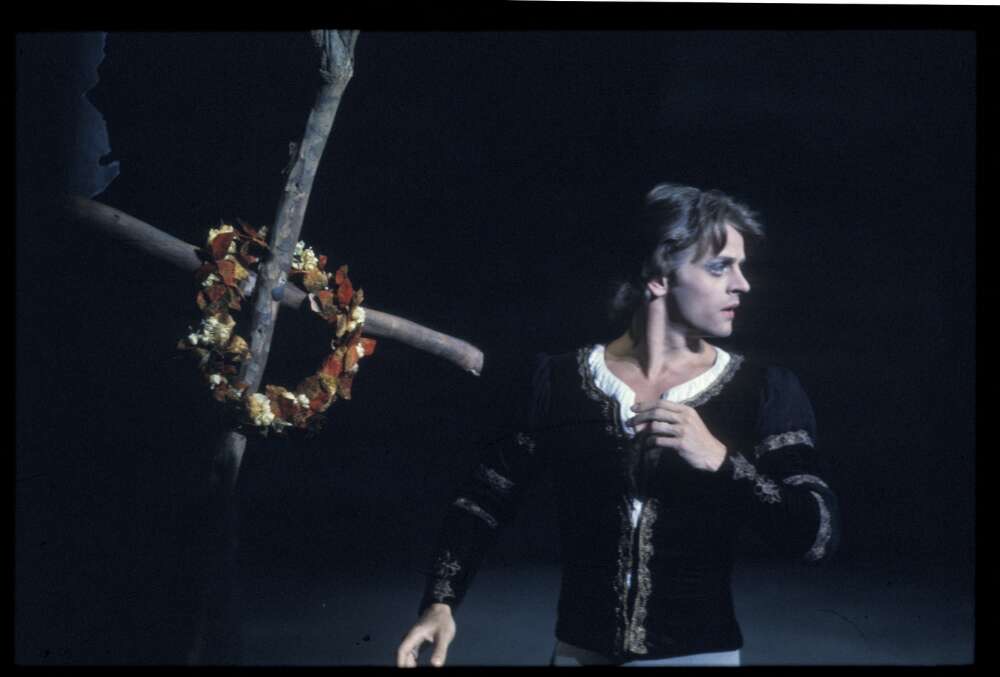

International Dance Day, 29 April, is always celebrated with a message from a major figure in the dance world. This year, 2025, the message came from Mikhail Baryshnikov whose comment read:

It’s often said that dance can express the unspeakable. Joy, grief, and despair become visible; embodied expressions of our shared fragility. In this, dance can awaken empathy, inspire kindness, and spark a desire to heal rather than harm.

Especially now—as hundreds of thousands endure war, navigate political upheaval, and rise in protest against injustice—honest reflection is vital. It’s a heavy burden to place on the body, on dance, on art. Yet art is still the best way to give form to the unspoken, and we can begin by asking ourselves: Where is my truth? How do I honor myself and my community? Whom do I answer to?

Latvian-born, Baryshnikov defected from the USSR in 1974. He has performed in Australia on various occasions, including in 1975 when he appeared with Ballet Victoria.

- Press for April 2025

Michelle Potter, 30 April 2025

Featured image: Autumn colours in Canberra, April 2025. Photo: © Michelle Potter