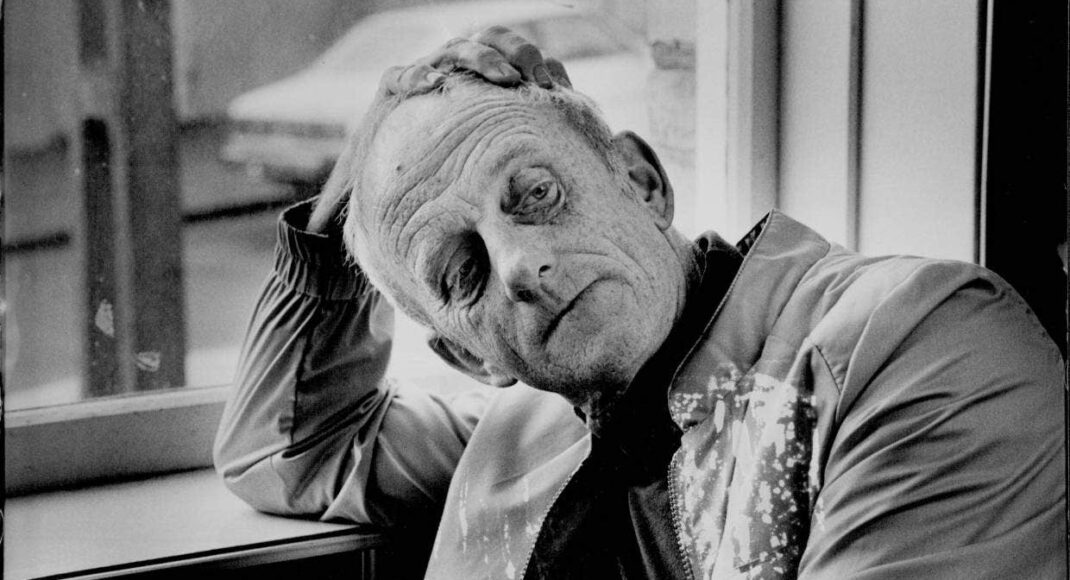

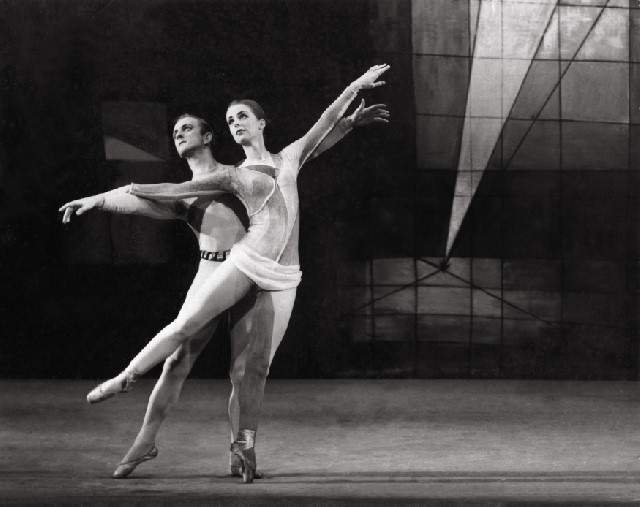

Shirley McKechnie, who has died in Melbourne at the age of 96, was one of Australia’s most influential dance educators. Born Shirley Elizabeth Gorham, she was educated at Albion State School and Williamstown High School. After matriculating from secondary school, and with the prospect of a career in science, began work in Melbourne in the research laboratories of the Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works.Ivey Wawn and David Huggins in a scene from Explicit Contents. Photo: Lucy Parakhina

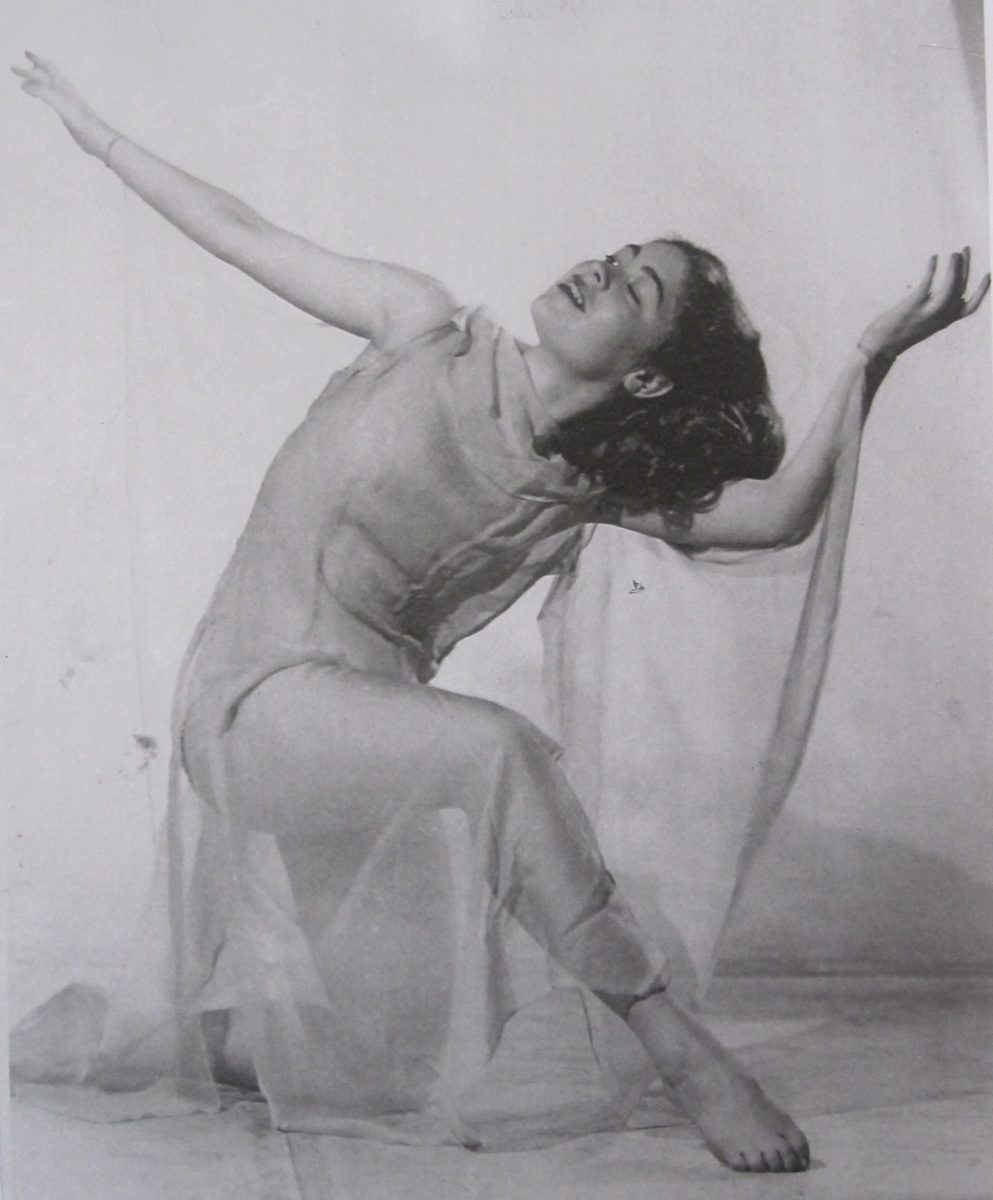

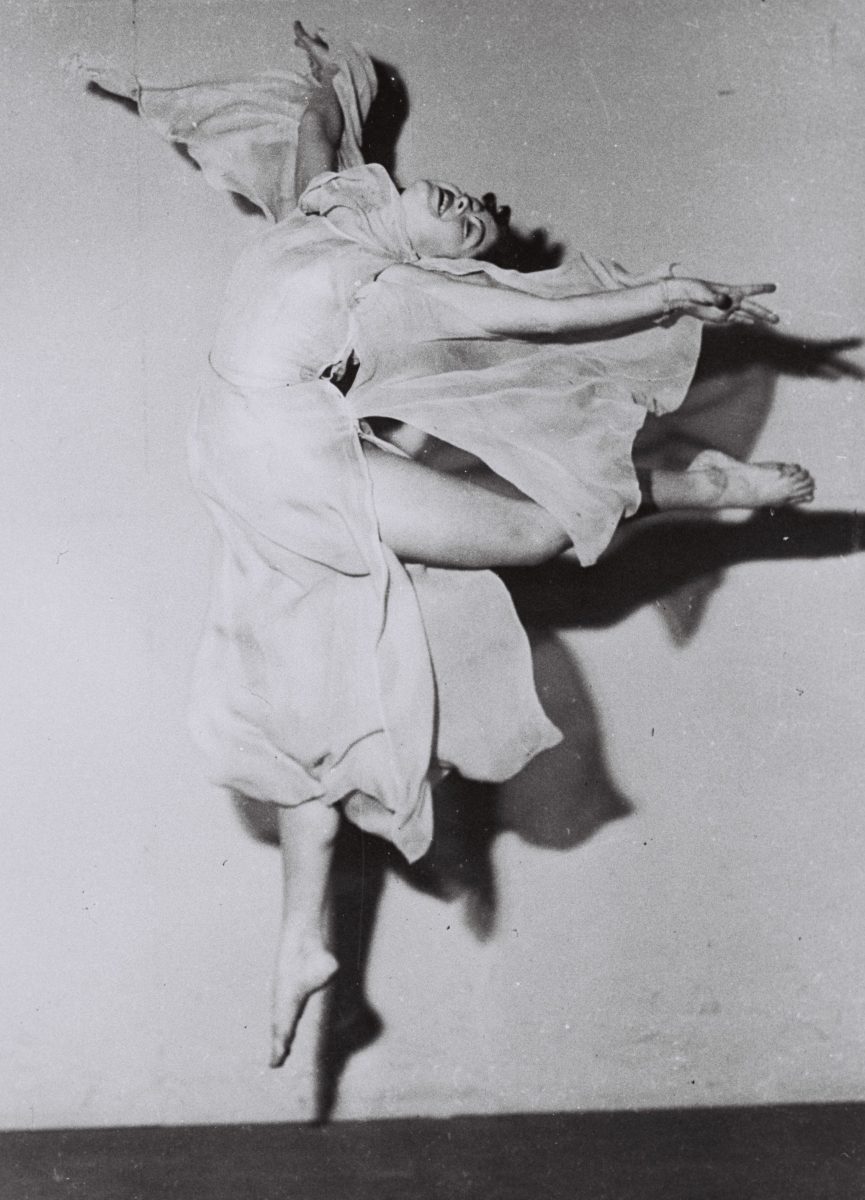

But her interest in dance and movement had begun when she was very young and, while engaged with the Board of Works, she continued her interest by taking dance and composition classes with Hanny Exiner and Daisy Pirnitzer, both of whom were exponents of the European modern dance technique as brought to Australia by Gertrud Bodenwieser. Exiner and Pirnitzer were associated with the Melbourne-based Studio of Creative Dance and McKechnie also began dancing with the performance group attached to that Studio.

In 1945 McKechnie began teaching dance at a small school she established with the encouragement and support of the Ferntree Gully Arts Society. She continued to teach at this school until her marriage to Ken McKechnie in 1948. After the birth of her second child, she established a second school in Beaumaris, Melbourne, in 1955. This school became the foundation for her long career as a teacher, choreographer and dance director.

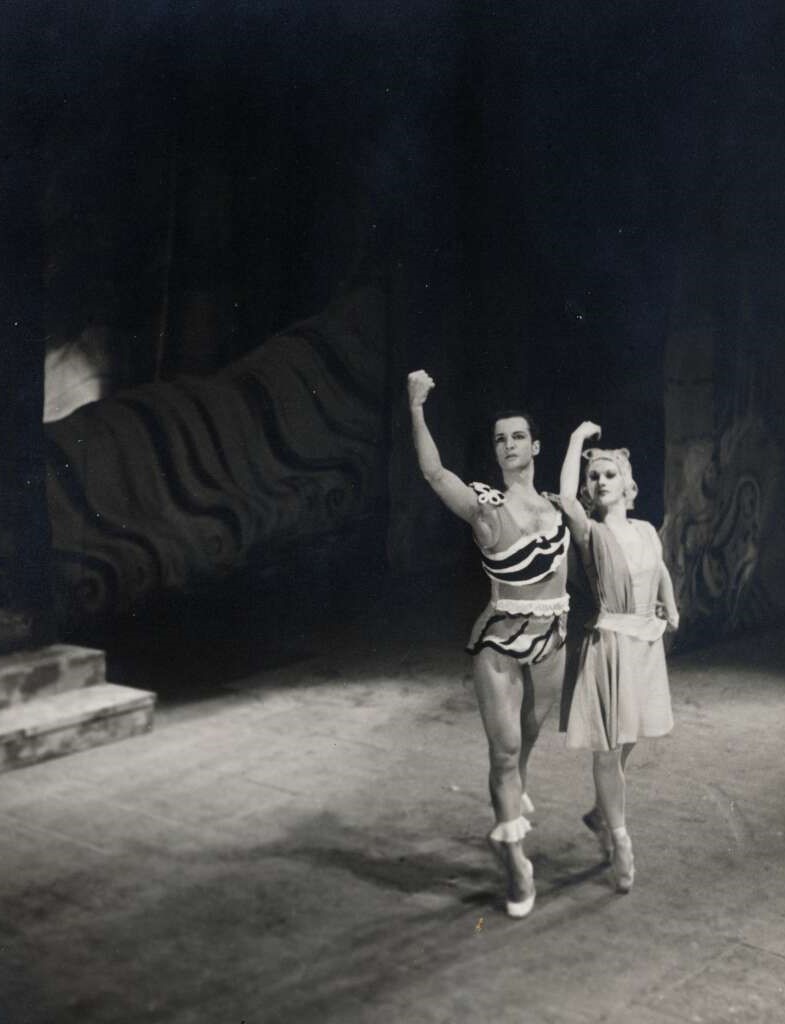

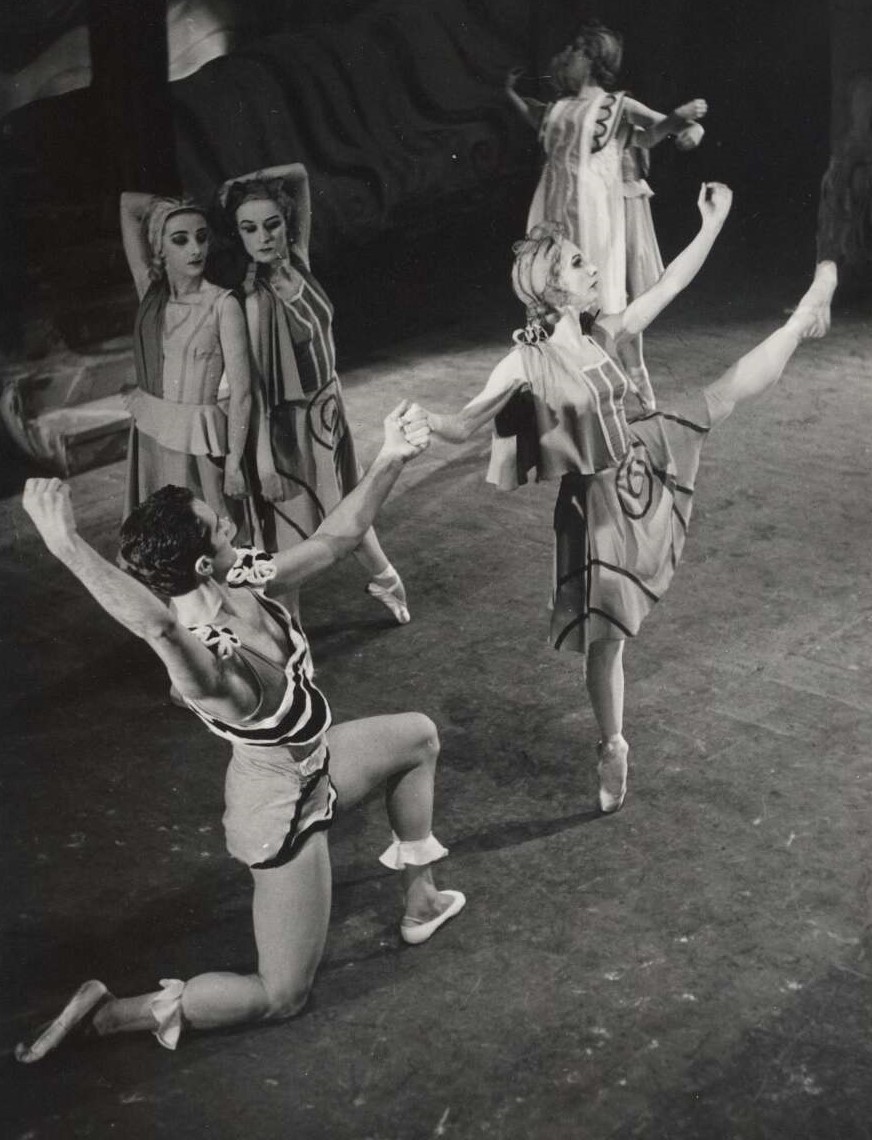

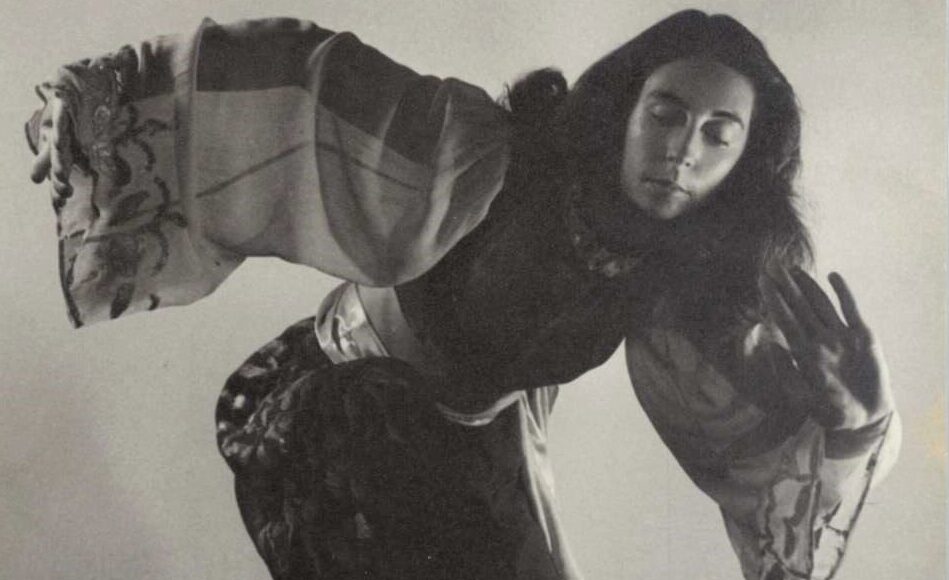

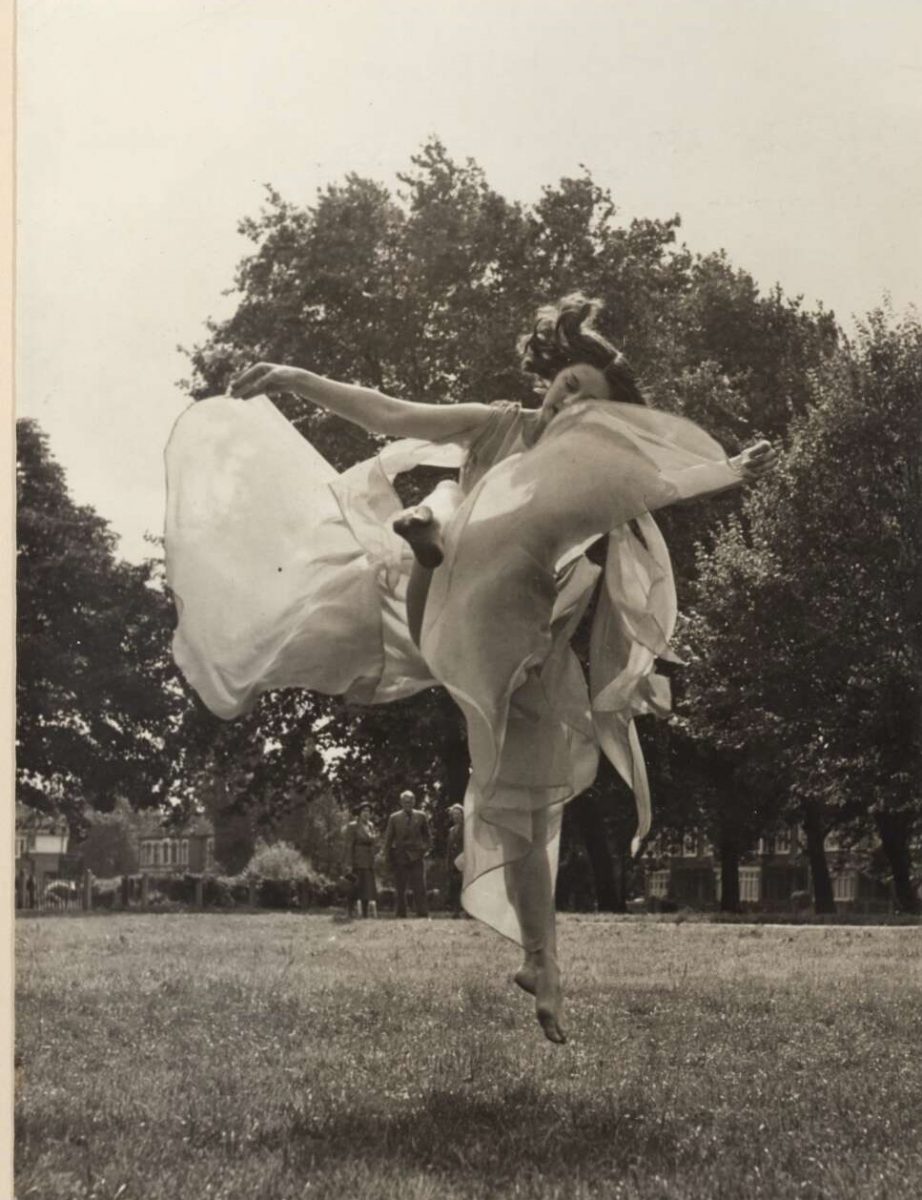

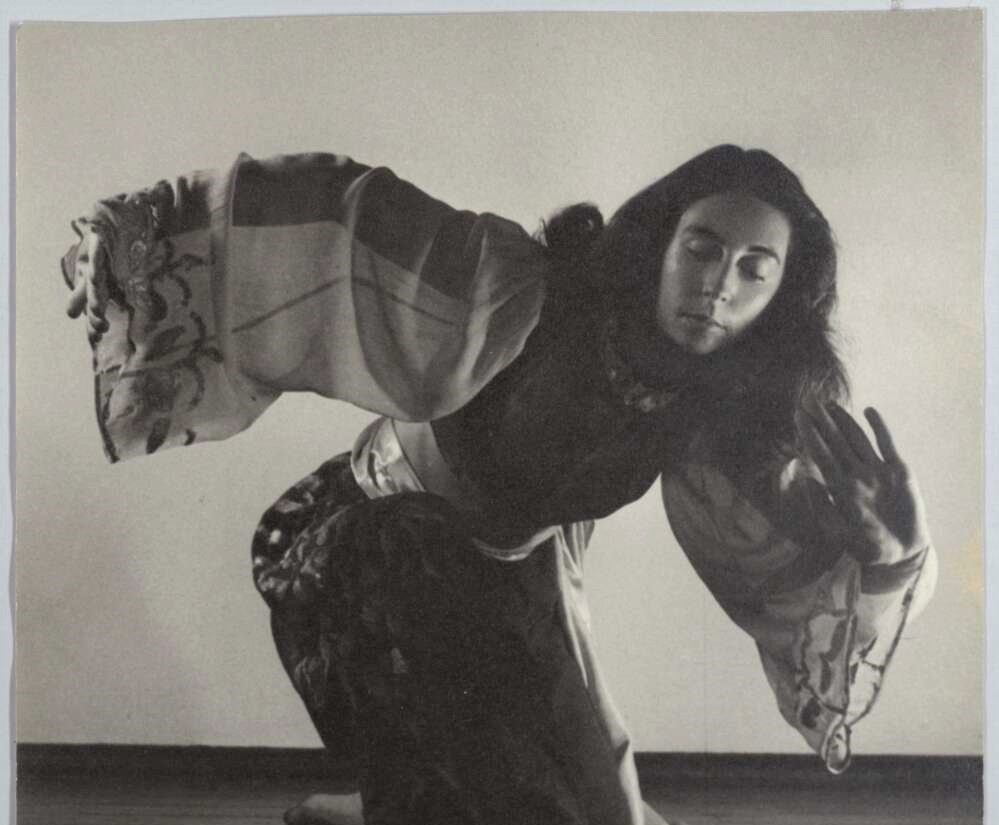

In 1963 McKechnie founded the Australian Contemporary Dance Theatre, whose dancers were drawn from the older students of her school. McKechnie was the company’s director and main choreographer between 1963 and 1973. During this time she choreographed a number of works for the company including Sketches on Themes of Paul Klee (1964), Earth Song (1965), Vision of Bones (1966), Sea Interludes (1966), Hymn of Jesus (1967), Of Spiralling Why (1967), The Other Generation (1968), Landscape of Dream and Memory (1970), The Finding of the Moon (1972), and Canon for Four Dancers (1973). During this period she also wrote and choreographed a lecture and performance titled The Dancer, the Dance and the Audience.

In the 1970s she worked closely with English dance advocate and educator Peter Brinson on two of the four momentous summer schools that took place at the University of New England in Armidale, NSW, between 1967 and 1976. The summer schools were initially an initiative of Dame Peggy van Praagh and the first two had a focus on classical ballet and audience development, and had broadly speaking a lecture/discussion-style emphasis. Those in which McKechnie and Brinson were closely involved highlighted choreography and creativity. More about the Armidale summer schools is at this link.

After graduating from Monash University with an honours degree in English literature in 1974 McKechnie founded and directed the first degree course in dance studies at an Australian tertiary institution at Rusden College, now Deakin University, in 1975. In her role as dance educator and advocate for dance she was also a co-founder of the Australian Association for Dance Education (AADE), now Ausdance, founding chair of the Tertiary Dance Council of Australia, founder of the Green Mill Dance Project, and a member of the research team for Conceiving Connections, a three year-study (2002-2004) building on the research project Unspoken Knowledges. Conceiving Connections aimed to increase an understanding of dance audiences by addressing problems that had been identified by the dance industry as critical to its viability among the contemporary performing arts in Australia.

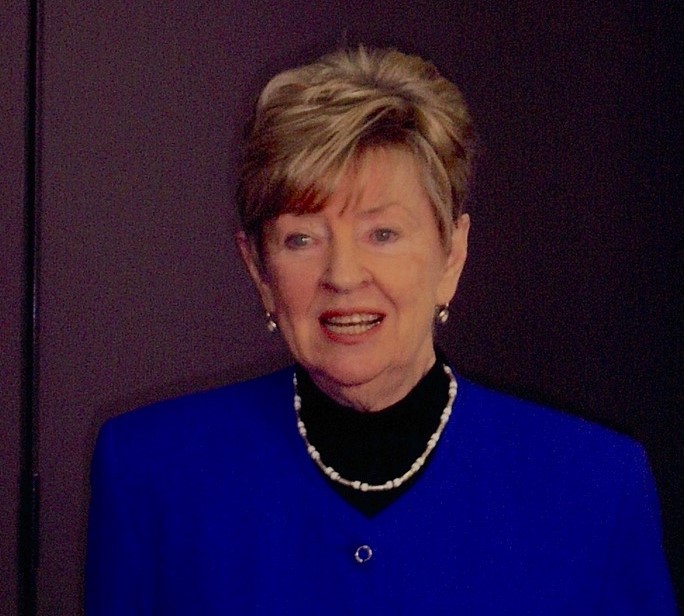

McKechnie went on to have an acclaimed academic career and received many awards and accolades. Her awards included a Kenneth Myer Medallion for the Performing Arts in 1993, the Ausdance 21 Award for outstanding and distinguished service, and two Australian Dance Awards, including that for lifetime achievement in 2001. She was made an honorary fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities in 1998, and an Officer of the Order of Australia in 2013. For a more detailed view of her academic career and her awards see Vale Shirley McKechnie AO on the Ausdance National website at this link.

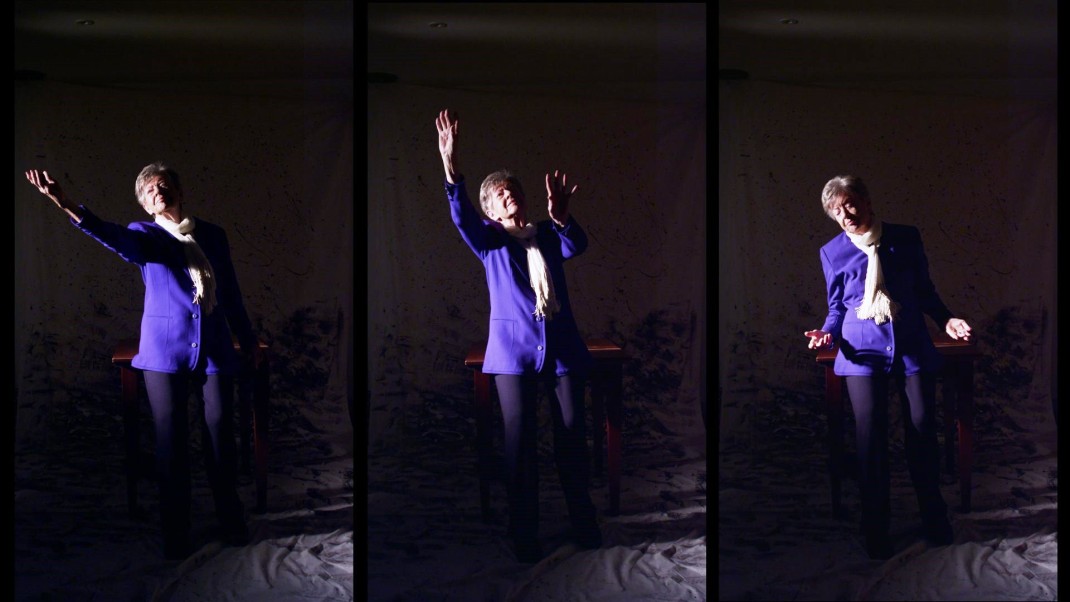

Perhaps what I admired most about McKechnie’s career was her ’never give up’ approach. Dance is an art form in which so many possibilities are available as one moves through life. McKechnie found and explored so many of them. I mentioned this aspect of her life in relation to a film made by Sue Healey in 2015 when I wrote:

McKechnie has influenced many people working in the area of contemporary dance in Australia and, when a stroke left her unable to continue her own practice, she turned to writing, largely in the field of cognition. As a result, this short film is not so much about how to continue to drive the body physically as one ages, but about how to reinvent oneself in order to remain active within the field of dance.

McKechnie spent her final years at Mayflower Brighton Aged Care and I recall that she was thinking of donating her dance library to Mayflower when she entered that centre. That way she would continue to have access to what had been written about the art form that she loved so much.

Shirley McKechnie is survived by her two sons, Garry and Graeme, and their families.

Shirley Elizabeth McKechnie, AO: born Melbourne 18 June 1926; died Melbourne 5 September 2022

Michelle Potter, 8 September 2022

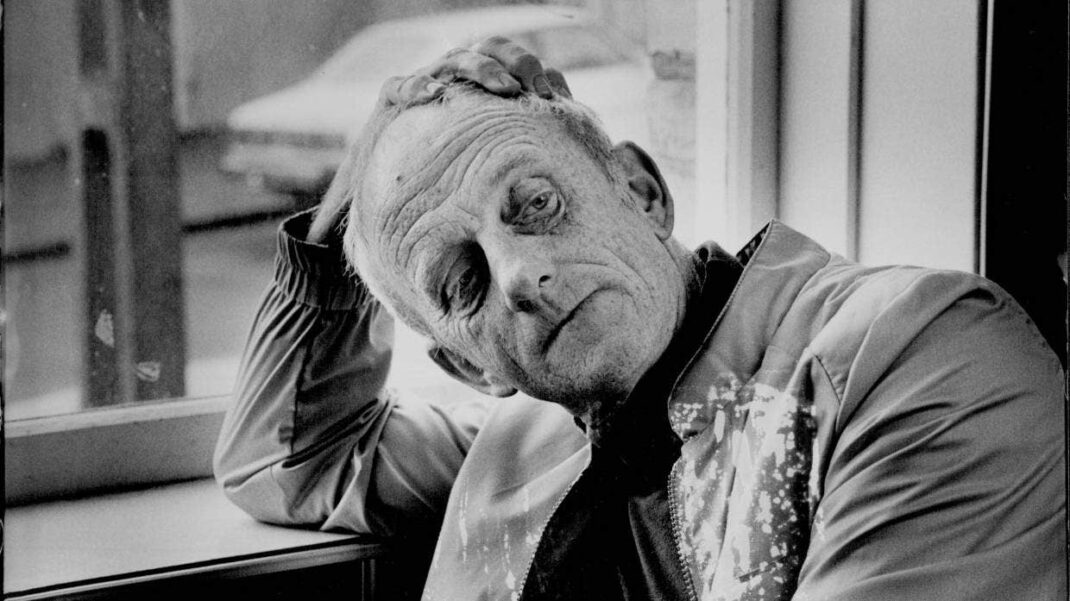

Featured image: Portrait of Shirley McKechnie, 2006. Photo: © Julie Dyson

Note on source materials for this obituary: Much of the material in this obituary comes from items held by the National Library of Australia in Canberra, including Papers of Shirley McKechnie (MS 9553), and a short biography from the website Australia Dancing (which was established at the National Library in ca. 2002 but which has not been active since 2012). I have directly taken sections from this biography, which I wrote in 2005. The Library’s material also includes oral histories with McKechnie as interviewee, and many oral histories that she recorded with contemporary dancers and choreographers for various projects in which she was involved, or which she initiated.