Some recent correspondence with a colleague in the United States highlighted in my mind the breadth of Paul De Masson’s international career and the fact that we often fail to recognise and acknowledge the role overseas experiences play in the careers of our artists. As a tribute to Paul’s varied activities in Australia and elsewhere, I have extracted just a few brief snippets from the oral history interview I recorded with him in Melbourne in July last year. The extracts are randomly selected from an interview that contains many other thoughts and ideas on a range of matters.

I have taken some liberties in putting together these short extracts as the spoken word, when transcribed verbatim, does not always lend itself to clear, readable text. Oral history is always better when it is listened to rather than read from a transcript. This is especially so in the case of Paul’s interview as his speech was colourful and peppered with many untranslatable noises to indicate various dance movements, the whipping of the head as one does a pirouette, for example. It also contains a range of different voices depending on which of his colleagues Paul is speaking about.

Paul’s interview (TRC 6328) is held in the Oral History and Folklore Collection of the National Library of Australia.

On Kiril Vassilkovsky, an early teacher in Perth

Kiril’s classes were very fast, lots of batterie ’cause he was very small. He used to do lots of pirouettes in class and lots of beats. And he used to dress for class. He used to wear a vest and trousers and shoes. He had special shoes made, very soft leather shoes. And they were plaited leather and special on the instep so he could point his foot. They had a heel ’cause he was small and he wanted to be taller. And so he demonstrated all these steps in a suit and tie. And he had immaculate nails. I noticed he was always manicured. His classes were very fast. And I’m not joking, Kiril taught me to do ten pirouettes.

On taking class with Roland Petit’s Ballet national de Marseille while on tour in that city with Disney on Parade

So I did class and I remember Roland stood right in front of me. He always did class every morning, at least the barre. And he always wore white. He had a bald, shaved head; I think he shaved it for a production he was doing. And there he was, right in front of me, and looking. I didn’t know it was Roland Petit, I didn’t know it was the director. And I remember everything was white, the shoes, the socks, the leg warmers. And he had a white dressing gown and a white towel. The afterwards they said to me ‘The director would like to see you.’ And so I went into this room and I was in shock. It was the same guy. And he said: ‘Well we are interested in you as a dancer. Do you want to come and join us?’

The follow-up story of Paul’s first few months with this company is particularly interesting.

On making up for the role of Quasimodo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame for the Australian Ballet

They’d had all these people from the film industry come in but they made all these plastic, silicon things. It didn’t work for the ballet because every time you did a pirouette it all flew off. So I designed my own make-up, which was basically Elastoplast and cotton wool. I put cotton wool and then stuck it down with Elastoplast, then more cotton wool then more Elastoplast. And it took me a long time, putting the cotton wool in the right place and then putting a make-up base on top of all that, filling in the cracks, and then using a brush to draw a face on that. But it was fantastic because it never moved and it was light.

It was this make-up that De Masson tore off in front of Peter Bahen, administrator, when the infamous Australian Ballet strike began.

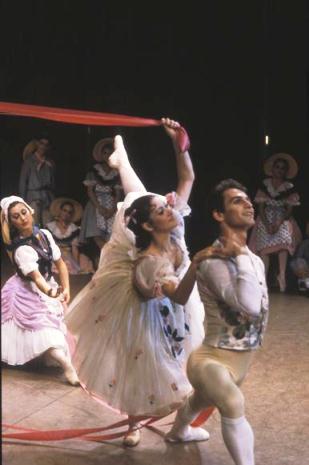

On dancing in Romeo and Juliet with the Australian Ballet

[Maina Gielgud] put me to do Romeo, Mercutio and Tybalt all in the same season in Sydney. Every second night I was changing, doing one or the other, which I found fantastic. I loved doing Mercutio, which was my premium role. Then when I got to do Romeo I thought that was fabulous, to actually have a chance to do Romeo. Then I couldn’t wait to get my hands on Tybalt. To do all three, and be different in all three, that was the challenge. But the other challenge was reversing all the sword fights. It was like sometimes I didn’t know who I was. I’d turn around and … but I managed. I got it done.

On his role as ballet master with the Australian Ballet

I used to love coaching, mostly the dramatic side of things. I think I was much better with individual rehearsals—principals and soloists—than I was with big corps de ballet work. Although now, now over all these years having worked in other companies as ballet master, I can handle that quite well now and I actually enjoy it a great deal. But I wasn’t enjoying it at first. I was much more comfortable with just a couple. But the highlight is sitting there and seeing the outcome. Just seeing the progression of the dancers, going from no idea of a role and then, after you’ve given them everything you could possibly give, them, seeing it suddenly click, seeing something happen. Sometimes it doesn’t happen and it’s disappointing. Then you have to find another way of explaining it. But the high points were watching achievements, getting people to act in a certain way.

On working with John Neumeier

It was fantastic working with John. It was exhausting because he is very demanding. And I had to learn a whole new repertoire, most of it John’s but not all. He did bring in other ballets and he did his own version of Giselle. He asked me basically to teach the principals the whole ballet. And then he tweaked it and put things in—like the entrance of Albrecht in Act Two. He made that into a contemporary solo, which really worked well.

Then he asked me to put the mad scene together very quickly for a Sunday chat with the audience. He was always giving you something to do, and involving you in the choreography. He had the Wilis screaming in Act Two because he had the Adam score and it said ‘Wilis enter, screaming hysterically’. He’d taped them first in the studio. And they came in screaming as they were doing the steps. And he did beautiful things like in the pas de deux in Act Two he had the Wilis standing along the side but instead of just being there rigid all the time, every now and again one would just drop her arms and look. And another would just go to her knee and cry. Towards the end of the pas de deux you noticed that everyone was in a different position. And one was quietly sobbing. It was very subtle. It was very nice.

On Singapore Dance Theatre

Soo Khim Goh [artistic director of Singapore Dance Theatre] liked the Western classical style of dancing and also the contemporary Western style but she was also very clever in keeping the Asian blend in there. It’s an Asian company. She got a wonderful choreographer from Indonesia, Boi Sakti, who did a full evening length piece called Reminiscing the moon. The stage filled with water, lights were floating, it was a whole journey watching this work. And she brought two or three different choreographers from Japan and China.

With my friendship with Roslyn Anderson we managed to get Jiri [Kylian] to let us have Stamping Ground for a month, or two months at a time rather than on a two or three year contract. Just because he knew we were a small company. And Ros loved coming to Singapore. But the one that I was really pleased to get was Forgotten Land. And we had Ohad Naharin, a lot of international choreographers.

And Jean-Paul Comelin came and we did his Giselle. We used students from the Central Ballet of China so we could do it because the company was only 21 dancers and we could bring it up to 30. The company always looked really professional. Sakura [his wife and dancer with the company] and I look back on it as being a really pleasant experience. We had a great place to live and just living in Singapore was really nice although it was sometimes a little bit warm and muggy. We were so close to everything. Half an hour to Phuket, well Krabi was our favourite. Or Sakura could go home to Japan, only five hours. Even Europe was only 12 hours away. So very good position.

Paul’s thoughts about Singapore Dance Theatre following Soo Khim Goh’s departure are a little different.

Final words

I don’t bear any grudges against anyone for anything that’s happened in my career. It’s always been a pleasure everywhere.

Michelle Potter, 14 February 2012

Follow this link to a list of the oral histories I have recorded over the past decades. Unless otherwise indicated all have been conducted for the National Library of Australia and are held in the Library’s Oral History and Folklore Collection. Further cataloguing and access details (some are available online) can be found on the National Library’s catalogue.

UPDATE February 2025: A more recent list of the oral histories I have conducted (arranged alphabetically) is at this link.