Digital screening, December 2022 (filmed during a September season from the Heath Ledger Theatre, Perth)

I first saw Douglas Wright’s Gloria in 1993 in Sydney when it was performed by Sydney Dance Company. Then it was a relatively new piece from Wright with its world premiere having taken place in Auckland in 1990. In 1993 I was the Sydney reviewer for Dance Australia so I am in the fortunate position of being able to look back at my reactions to that early production. In fact, a copy of that review appears on this website at this link.

The features of Gloria that thrilled me in 1993 are also powerful features of the Co3 production —its life affirming message, the witty choreography, the unusual and challenging connection (or not) between music and dance, and in general the vigour and vitality of the work. But on this occasion I saw it as a streamed event and, generously from Co3, the Perth-based contemporary company led by Raewyn Hill, I was able to watch it over a 48 hour period. This meant that I had time to go back and look more closely at certain sections. While every section had its highlights, two sections and one particular moment stood out for me.

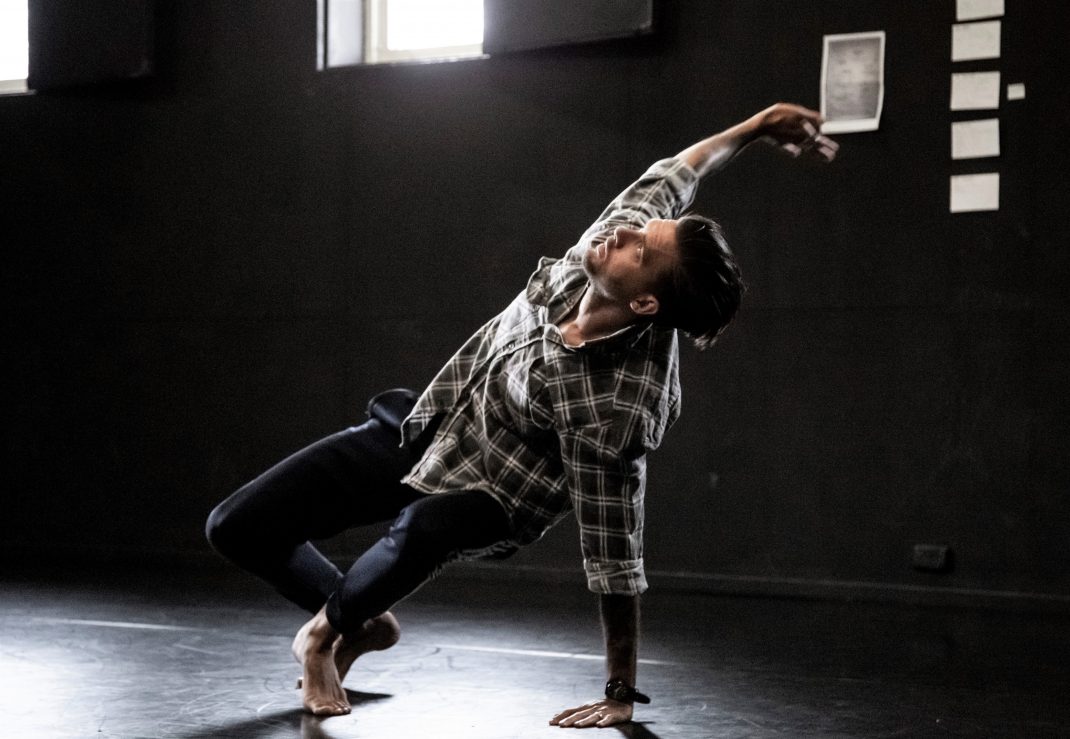

The one particular moment came at the end of the first movement of Vivaldi’s Gloria, to which the work is danced. The dancers began with quite slow, unison movement that turned into energetic leaps, turns and fast running down the diagonal. As the dancers left the stage, and as the first movement was coming to an end, a single male dancer, Sean MacDonald whose connections with Gloria go back to a 1997 production, was left alone on the stage. His final jump ended with him lying on his back, legs and arms moving slowly as if he was running in that prone position. He rolled over, slowly stood up, and lifted his arms to the front, palms facing upwards. The lights faded but the music continued and the power of MacDonald’s final, simple movement was breathtaking.

Another section that moved me immensely was performed to the ‘Domine Deus’ section, sung (according to the credits that ended the stream) by soprano Sabra Poole Johnson from St George’s Cathedral Consort, the group that provided the vocals for the Vivaldi score. This section began with a group of five dancers moving slowly in a sculptural formation but eventually separating with four sliding off leaving one dancer (Francesca Fenton I believe) alone. She began her solo on the floor but slowly assumed a standing position and, in so doing, seemed to be exploring her physical existence before she broke into a waltz-like dance full of grace and fluidity. Like MacDonald before her, as her dance came to and end she lifted her arms, stretching them forward with palms facing upwards as if to announce she had discovered her identity, her existence, herself.

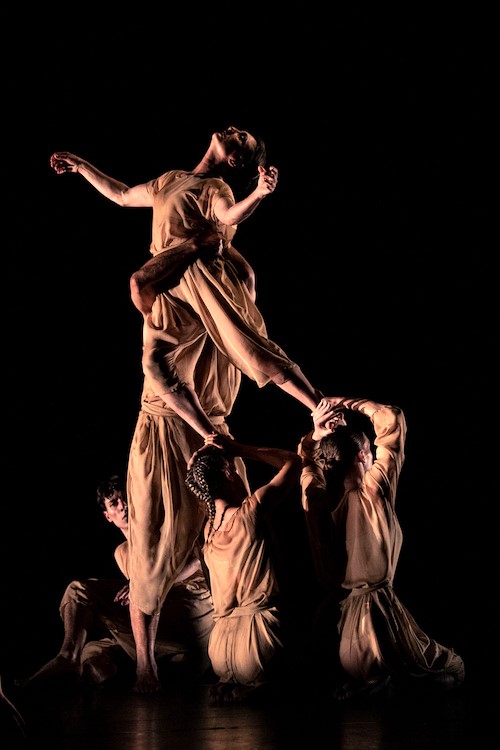

I also enjoyed the section danced to the movement ‘Et in terra pax’. It featured Claudia Alessi who had danced in Gloria in 1991 when it was staged for the Perth Festival by Chrissie Parrott. What made this section so appealing to me was the sculptural qualities of the choreography, which in fact were noticeable throughout the work, although perhaps not to the same extent as in ‘Et in terra pax’.

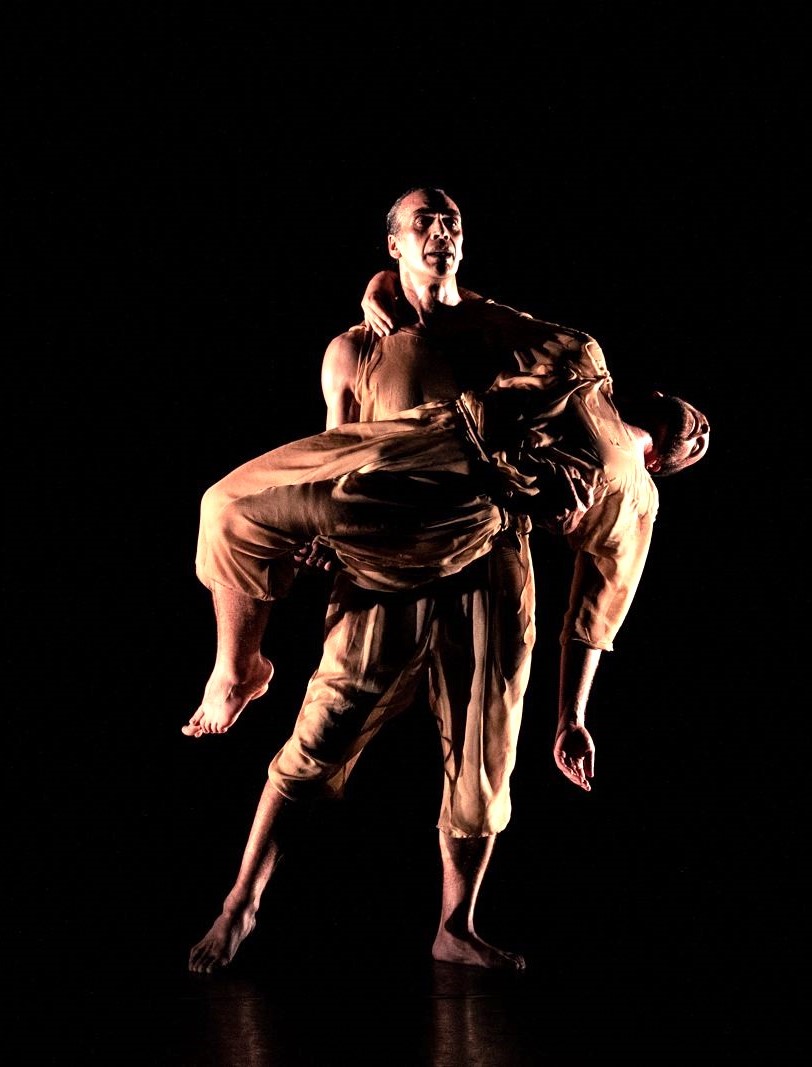

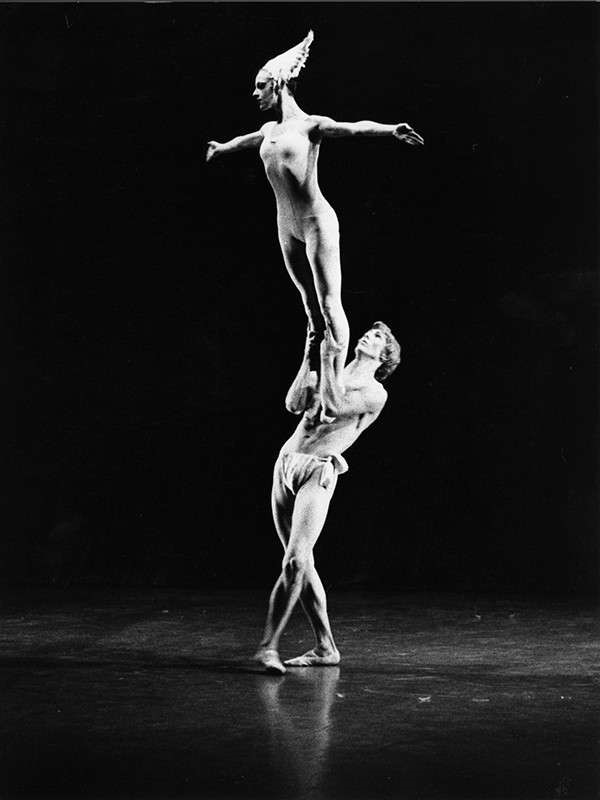

There were of course many other moments that continue to resonate: the joyous quality of the dance to ‘Laudamus Te’ and the duet between two male dancers (Sean MacDonald and Scott Galbraith I think) in which we witnessed the changing nature of human relationships. Also great to watch were those moments when a dancer was held and swung back and forth by two other dancers as others ran underneath and around the activity. But I guess I go back to my original review for Dance Australia and confirm more than anything that Wright’s Gloria is life-affirming whatever one might think of specific sections. Wright uses dance to convey a message about humanity. Simple but astounding.

I was lucky to be able to keep going back to watch sections of Gloria but I am sure I missed a lot by not seeing it live, especially as the music was played live by a chamber group from the West Australian Symphony Orchestra and sung live by the St George’s Cathedral Consort, with the whole conducted by Dr Joseph Nolan. Nevertheless, the sound quality of the streamed version was just beautiful and I absolutely loved being immersed in this production from Co3 of Douglas Wright’s spectacular Gloria.

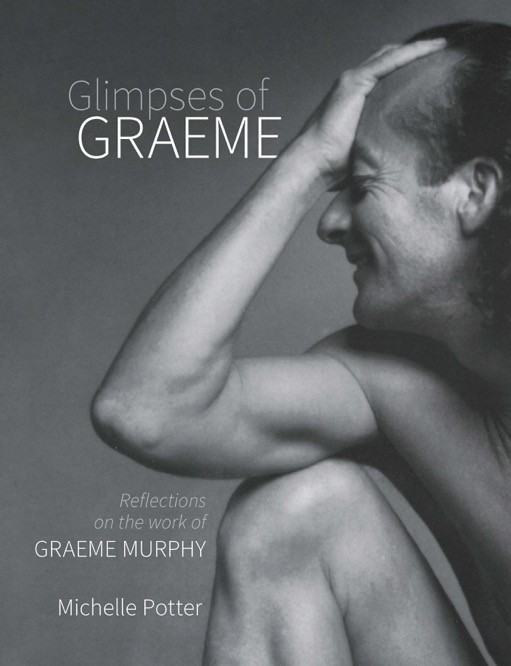

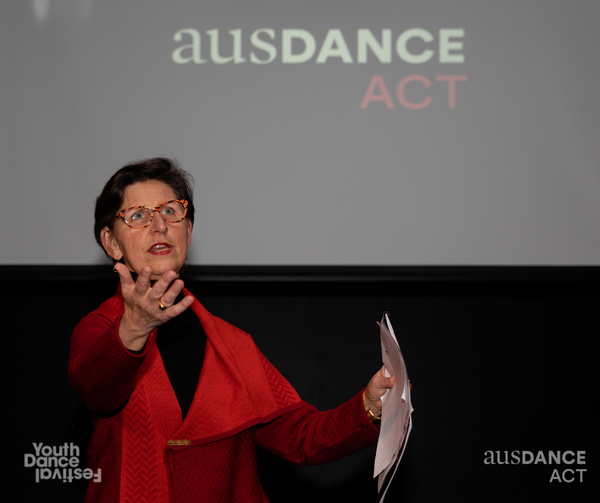

Michelle Potter, 25 December 2022

Featured image: Scene from Gloria. Co3, Perth, 2022. Photo: © Shotweiler Photography

At the time of writing, the streamed Gloria is still available to watch for the small price of AUD 19. The offer is available until mid-January. See ‘Watch at home’ at this link.

ID; A photo of a white male, slim build, 6′ 2″ tall, wheelchair user with a shaved head, green eyes and sculpted facial stubble, wearing a black at cap, black jumper and a black & grey scarf around his neck. Poised in front of a grey background. Photo credit; Maurice RamirezMarc is a Disabled choreographer, director and dancer. His lecture titled ‘Point of the Spear’ will share his personal experience of the importance of being an advocate for accessibility and inclusion. How, collectively, we all need to work together to be Inclusive in our thinking and actions to make the world equitable for all.

ID; A photo of a white male, slim build, 6′ 2″ tall, wheelchair user with a shaved head, green eyes and sculpted facial stubble, wearing a black at cap, black jumper and a black & grey scarf around his neck. Poised in front of a grey background. Photo credit; Maurice RamirezMarc is a Disabled choreographer, director and dancer. His lecture titled ‘Point of the Spear’ will share his personal experience of the importance of being an advocate for accessibility and inclusion. How, collectively, we all need to work together to be Inclusive in our thinking and actions to make the world equitable for all.