- EAT

Canberra’s youth dance organisation, QL2 Dance, runs an annual project for younger dancers in Canberra and beyond. This year, with a program called EAT, the theme was food, including marketing issues associated with what we eat.

For various reasons, I looked with different eyes this year and was impressed with how the choreographers, all professionals working with contemporary dance, handled the situation. With technical capacity varying so much between the dancers (they ranged in age from 8 to 18), it was illuminating to see the theatrical concepts that were being taught to these young people—how to make entrances and exits, how to occupy the performing space, how to be in line and so on. In fact, young people in Canberra are lucky to have the opportunities that QL2 offers. May it continue.

- The Royal Ballet’s Australian tour, 2017

The Royal Ballet will tour to Australia (Brisbane only as part of QPAC’s International Series) in June and July 2017 with a contemporary repertoire of Woolf Works from Wayne McGregor and The Winter’s Tale from Christopher Wheeldon.

The Royal last visited Australia in June 2002 when Ross Stretton was the company’s artistic director. They brought Swan Lake, Giselle, and a mixed bill comprising Tryst, Marguerite and Armand and The Leaves are Fading. For that tour I wrote a piece for DanceTabs (sadly a link is no longer available) subtitled ‘Some personal reflections on the recent Royal Ballet tour to Sydney…’. Here is what I wrote as a conclusion:

The highlights

To die for: Alina Cojocaru’s double attitude turns in Giselle. So turned out, so light, so controlled. Divine.

Partnership of the season: Alina Cojacaru and Johan Kobborg in Giselle and Leaves. This partnership looks good physically and Cojocaru draws out a tenderness in Kobborg that adds an emotional dimension to the technical strength of the partnership.

Favourite moment: Belinda Hatley giving an audible whoop of excitement before launching into a joyous, absolutely irresistible Neapolitan dance in Swan Lake.

Australian moment: Leanne Benjamin’s deliciously playful but very mature interpretation of the central pas de deux in Leaves.

Non-dancing moment: The backcloth/lighting in Tryst, which had the dramatic and expressive qualities of a Mark Rothko painting.

Most annoying comment: ‘Darcey Bussell fell over in the fouettes in Swan Lake on opening night.’ (What happened was that she turned 27 or 28, went for a big finish, did a triple pirouette, had too much momentum but couldn’t go for four, finished slightly off balance and ended the sequence with a bit of a hop as she put her back foot down). But what attack! She was ferocious.

Favourite comment: ‘I had the two best cries I’ve had for years.’ (On the Cojacaru/Kobborg Giselle).

Disappointment: Neither Jonathan Cope nor Massimo Murru as Armand could match Sylvie Guillem’s Marguerite.

Dancer to watch: Corps de ballet dance Lauren Cuthbertson who made her presence felt in a soloist role in Tryst.

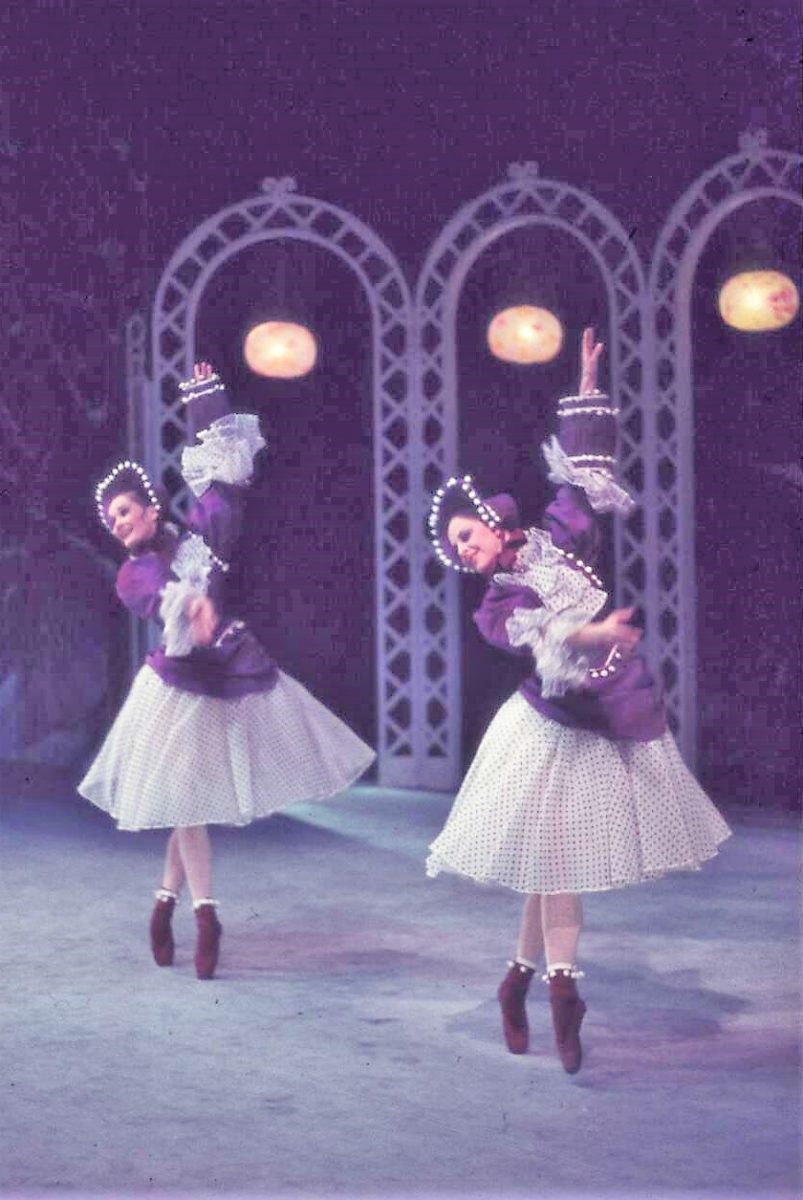

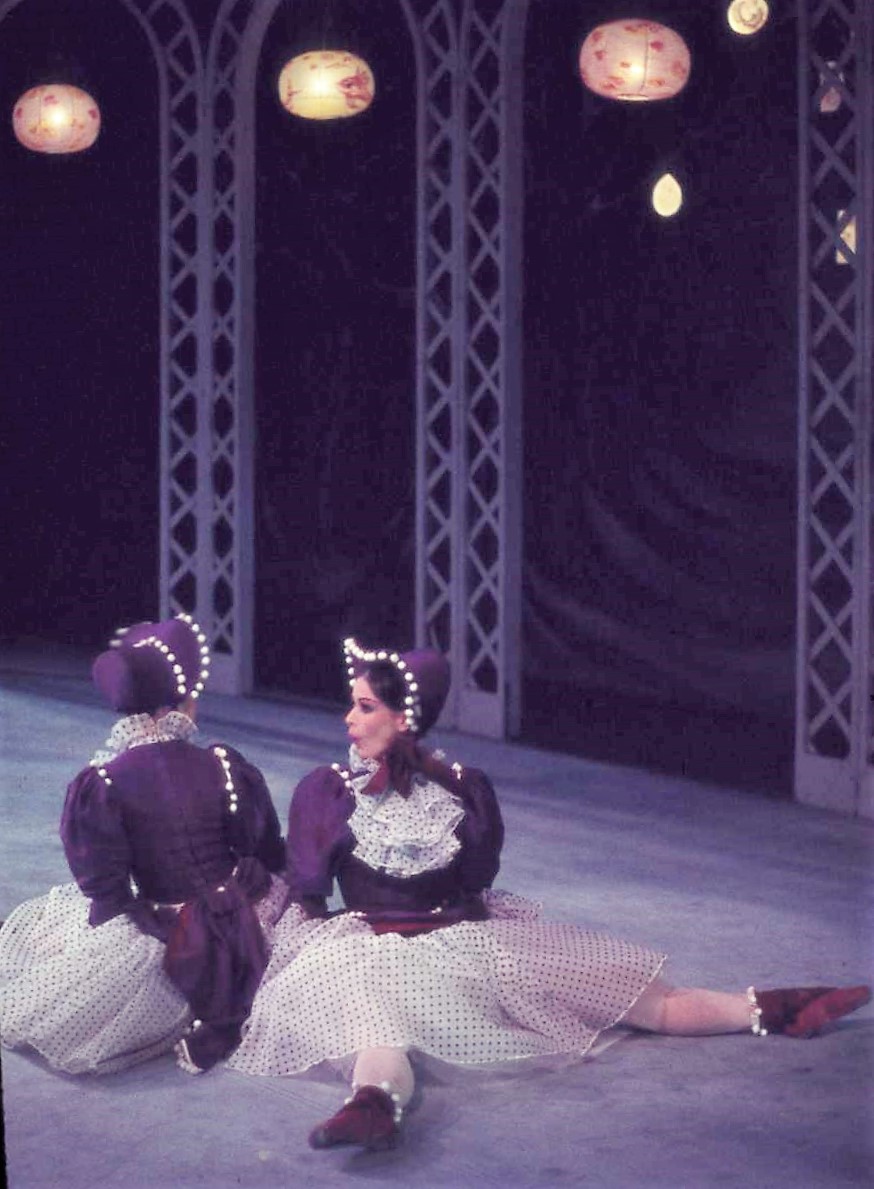

What an astonishing season that was! But recent viewings of the Royal in London suggest we can expect something spectacular this time too. In the meantime, I found the two images below from Les Patineurs. They are from a much earlier visit from a touring arm of the company, when the company was, in fact, in a state of flux (which I won’t go into now)!

Michelle Potter, 31 October 2016

Featured image: Scene from EAT, QL2 Dance. Photo: © Lorna Sim