14 April 2023. Playhouse, Queensland Performing Arts Centre, Brisbane

Queensland Ballet’s current production of Giselle owes its staging to Ai-Gul Gaisina, Russian-trained dancer with a stellar career in Australia as a dancer, teacher, coach and, more recently, stager of ballets from the traditional repertoire. The first thing to say about this production, originally made for Houston Ballet in 2011, is that the narrative is strong and clear from beginning to end. This is not always the case with many productions of Giselle where emphasis is so often given to technique and its relationship to the Romantic style, rather than to making the storyline a feature. This is not to say that technique was forgotten in the Queensland Ballet production. In fact, the dancers, clearly well-rehearsed, performed beautifully in both acts. But it was a real treat to have a strong storyline in which to become immersed.

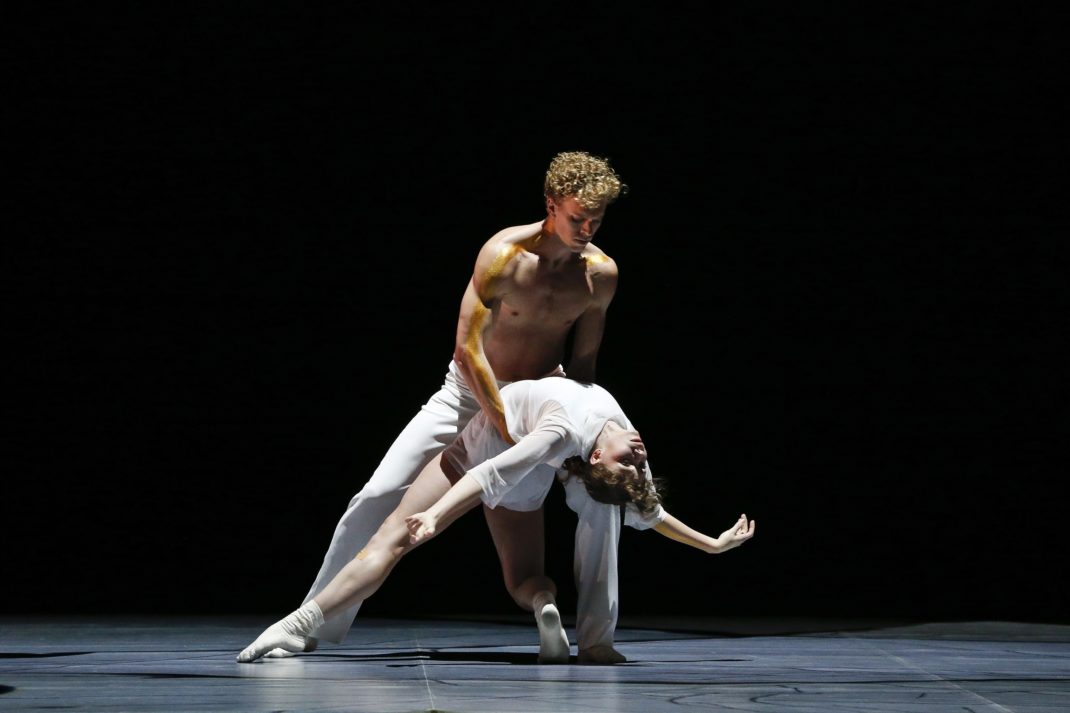

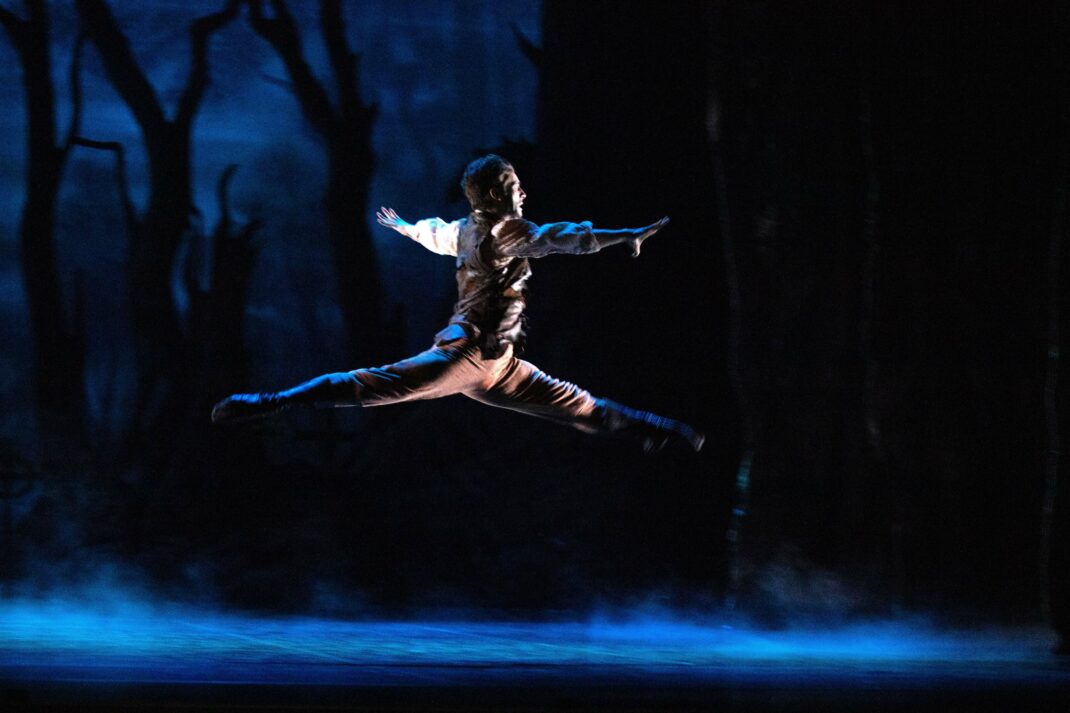

Mia Heathcote and Patricio Revé danced the leading roles of Giselle and Albrecht and presented us with some memorable moments of dancing, especially in Act II. Revé’s solos were stunning for the most part, including his 32 entrechats six as he danced to avoid death from the Wilis, while the various pas de deux between them were filled with gentle emotion.

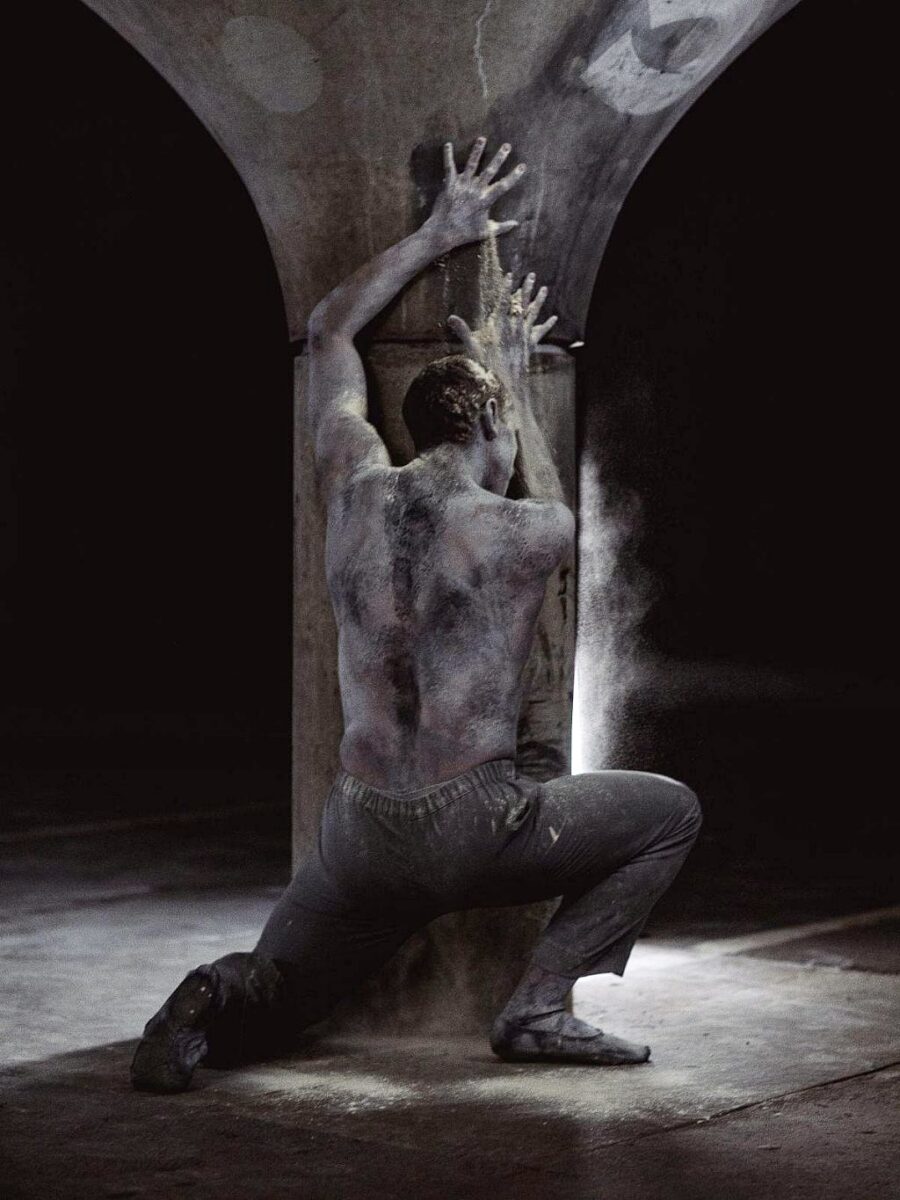

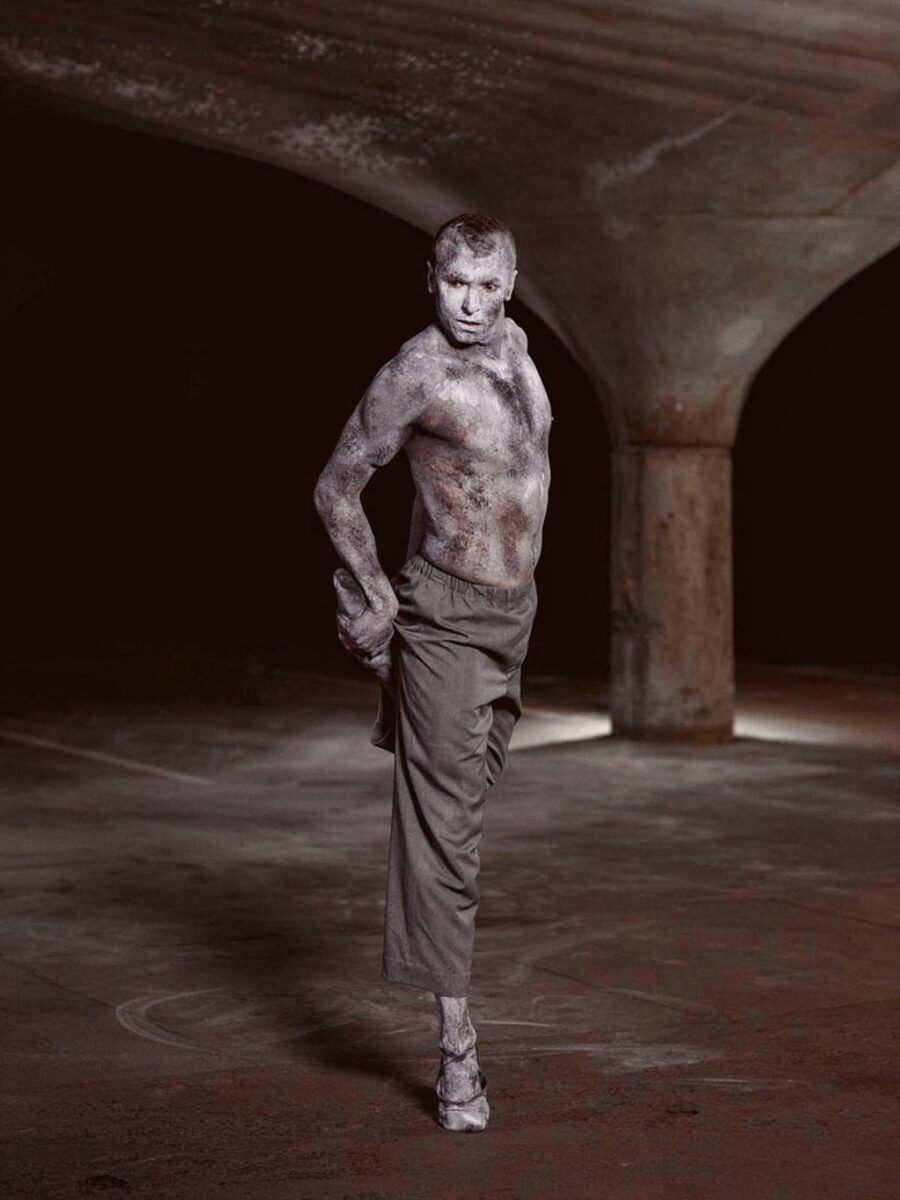

Vito Bernasconi was a standout performer as Hilarion, the forester whose love for Giselle is not returned and who unmasks Albrecht as the royal prince that he is. Bernasconi’s suspicion and anger as Act I unfolded were palpable as was his dramatic dancing in Act II as he tried, unsuccessfully, to avoid death.

I was also surprised by parts of the Adolphe Adam score, played by Queensland’s chamber group, Camerata, conducted by Nigel Gaynor, which opened up new insights for me. In particular I was transfixed by the introduction to Act II in which that recurring musical motif for the Wilis was juxtaposed with the ominous sound of drums spelling impending disaster.

In a not so positive note, I would have liked the characterisation of Berthe, Giselle’s mother danced by Lucy Green, to have been stronger. In my mind Berthe has to be an older woman who is not only concerned about her daughter’s health, but is also somewhat superstitious. Green’s mime scenes stating that if Giselle keeps dancing she will die were very clear. But it is not just a medical matter. The recurring Wili musical motif keeps appearing in Act I but it is not often that anyone onstage recognises those motifs. Berthe and the rural village in which Act I of the ballet is set has to be superstitious. It’s the mid 19th century. So why is Berthe always just worried from a medical point of view? I want Berthe to be concerned about the Wilis as well as the heart issues. Anyway, that’s just a gripe of mine.

I also wanted Myrthe, Queen of the Wilis in Act II (danced by Yanela Piñera), to be a stronger character. To me, in this production she didn’t seem capable of being in control of her realm, which she needs to be. She isn’t meant to be a pleasant character. I also had problems with the lighting of Act I (lighting design by Ben Hughes), which at times seemed too bright, or too strong somehow, thus making the muscle structure of some the male dancers seem unattractive.

Despite my gripes and grumbles, this was probably the most interesting staging of Giselle I have seen since the exquisite production by the Paris Opera Ballet in Sydney in 2013, and the one I will never forget from Sylvie Guillem and the Finnish National Ballet way back in 1998. The problem arises, however, that when there are many outstanding aspects to a work, as there were in the Queensland Ballet 2023 production, those bits and pieces that are not quite brilliant tend to be magnified in a critic’s mind. Nevertheless, while I stand by my criticisms, I have to add that I loved seeing this production and have nothing but praise for those who made it happen.

Michelle Potter, 15 April 2023

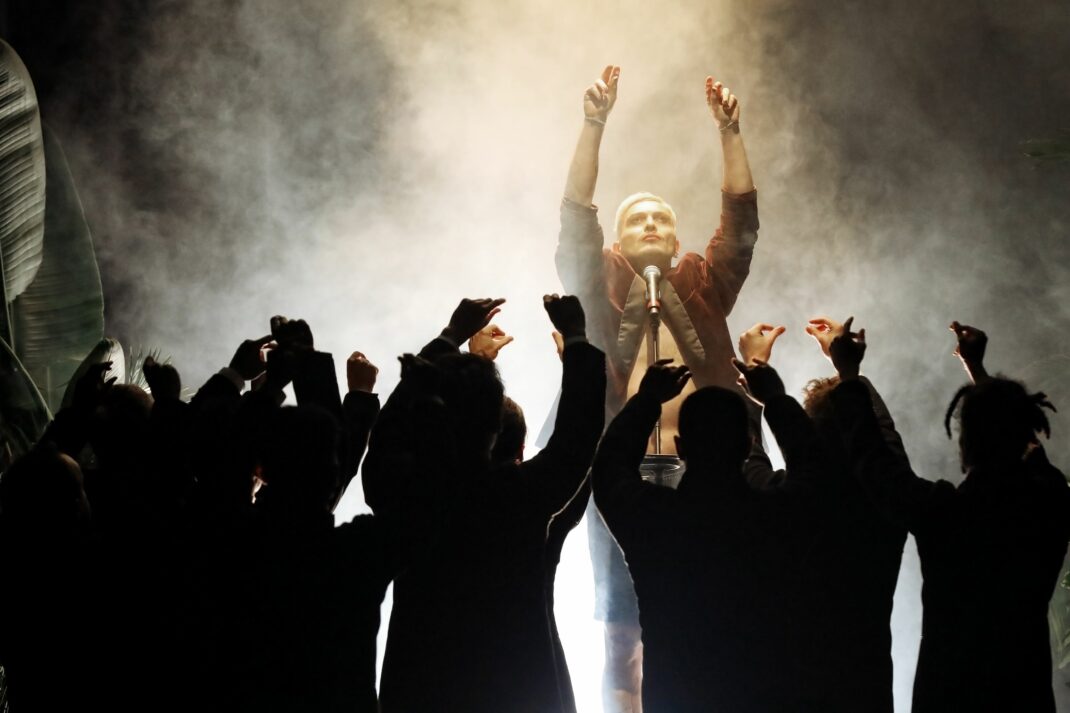

Featured image: Three Wilis in Giselle Act II. Queensland Ballet, 2023. Photo: © David Kelly

Another personal note (gripe):

One thing that I find particularly annoying is the way Queensland Ballet audiences applaud at what I think are inappropriate times. It means that it is sometimes impossible to hear the music that signals the next section of the dancing and sometimes that applause even comes mid-stream—that is before a specific and important section of the production is finished. It’s lovely to know that the audience appreciates the outstanding dancers of Queensland Ballet, but it seems to be getting out of control unfortunately. Please just hold back a little.