30 March 2018, Courtyard Studio, Canberra Theatre Centre

Many words come to mind when thinking about Alone, a work by Jack Riley made on four dancers: confronting, demanding, mesmerising, mysterious, thought-provoking, physical, dangerous, even a little spooky at times.

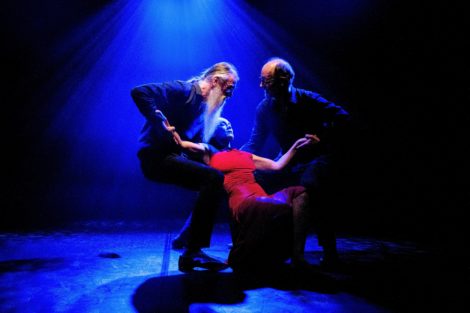

After a bit of silence while we contemplate a shape under a grey blanket, Alone begins with a bang! Riley enters suddenly from a door at the back of the performing space. He flings it open, strides in, closes the door with a huge bang. We notice he is wearing a black, unadorned mask. He proceeds to shine blue lights on the shape in the middle of the floor and around the studio. Then he rips off the blanket and exposes a naked body, lying curled up. Where is this going we wonder? The body is that of Nikki Tarling and slowly, so slowly, she moves her body, mainly her limbs, until Riley arrives at her side and proceeds to dress her in baggy trousers and a close fitting top.

Throughout this opening adventure I am a little spooked by a black-clad, hooded figure who has quietly appeared and is leaning against a side wall. Throughout the evening he slinks, ever so slowly, around the walls of the studio until, in the last moments of the performance, he has reached the wall on the other side and is hovering near another curled up, naked figure. What role does he play?

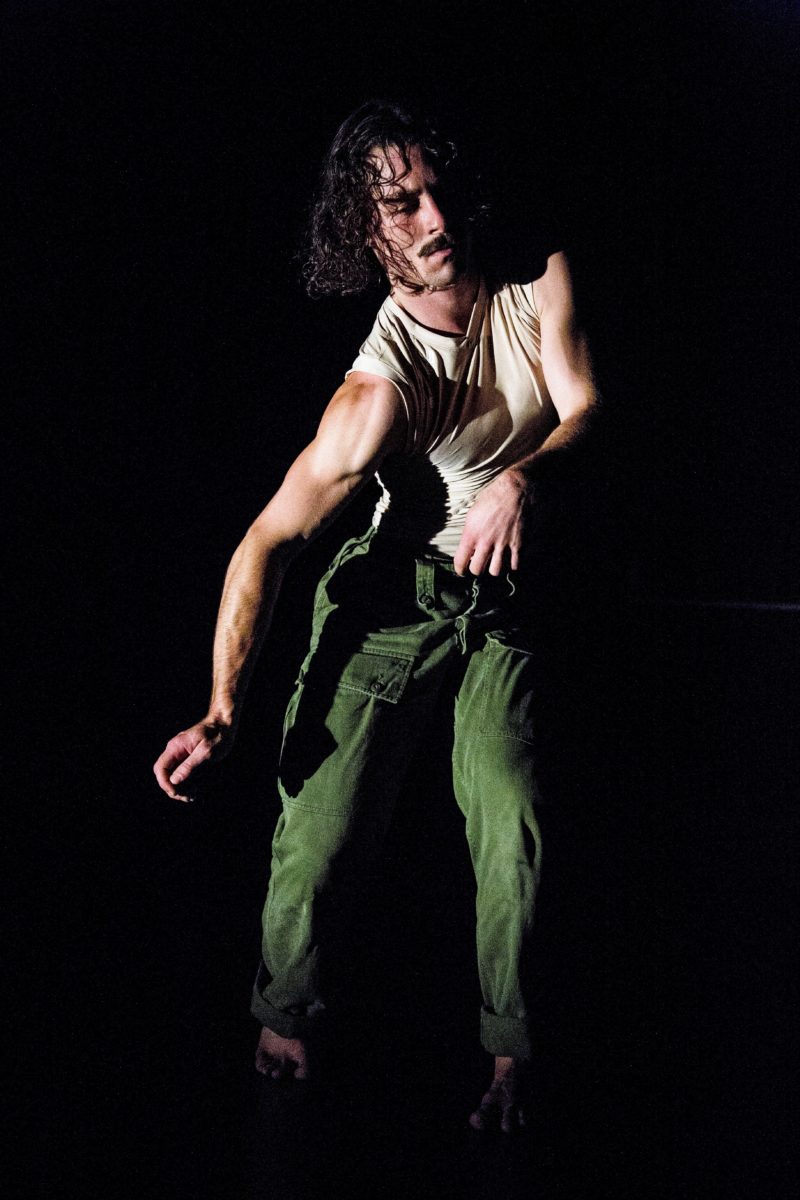

Between the beginning and the end there is some strong dancing. The highlight is a duet between Riley and Tarling, sometimes involving two long rods, initially joined together. But once the rods are separated they become a little like weapons and the relationship between the two dancers has elements of a duel, a challenge, and a desire to gain the upper hand. There are moments that recall moves in fencing and the martial arts, and others of extreme physicality when bodies are thrown around sometimes to the extent that I think the dancers must have fallen and been injured. But no, it’s just Riley’s extreme choreography. It is exciting to watch, heart in mouth.

Eventually, Riley relinquishes the mask, which is taken and worn by Tarling. Later, Riley has a solo in which he shivers and shakes. It is more emotional than physical, but it makes a powerful impact. And finally Tarling smashes the rod over Riley. It puts her in control.

What about the hooded character and the second naked body in the upstage corner? Well, to me in the end it seemed that death was hovering over life, and the entire show seemed like a confrontational look at forces that follow us throughout our life. I love a show that gives me the opportunity to have a personal interpretation of a performance, as Alone did. It was also a well structured and well danced show and was a definite step forward for Riley.

Michelle Potter, 31 March 2018

Featured image: Nikki Tarling and Jack Riley in Alone, 2018. Photo: © Lorna Sim

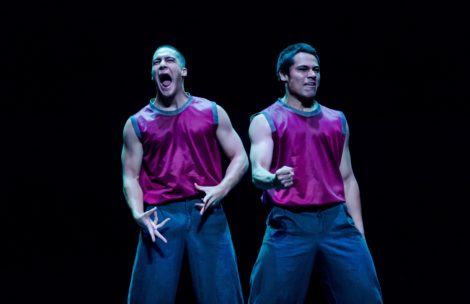

NOTE: I am sorry not to be able to mention the soundscape that accompanied the show; nor the names of the two other male dancers, who played minor roles in terms of dancing, but whose presence was essential (at least in relation to how I interpreted the work); nor the designer of the very interesting lighting. There was a list of those involved in the show stuck to a wall in the foyer, but the role each played was not identified. Something for next time?