- Ballet Rambert Australasian tour

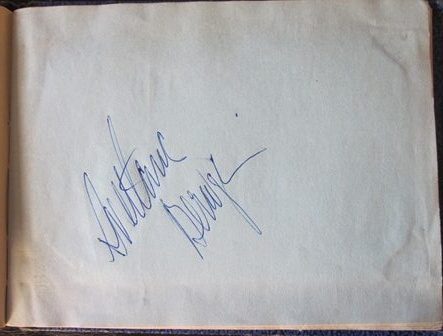

I was delighted to find, during my recent research in the Rambert Archives in London, an album, currently on loan to the Archives for copying, assembled by dancer Pamela Whittaker (Vincent) during the Ballet Rambert’s tour to Australia and New Zealand, 1947–1949. What struck me instantly was the fact that this company enjoyed a similarly social time in Australia and New Zealand as did the Ballets Russes companies that preceded Rambert. I hope to pursue this a little further in a later post but in the meantime the featured image (above) is a photo from Pamela Whittaker’s album. Below is another image from that album.

- Kristian Fredrikson Scholarship 2014

The Kristian Fredrikson Scholarship for 2014 has been awarded to West Australian designer Alicia Clements. For more about Alicia’s work see her website, but below is a costume for the character of Nishi from The White Divers of Broome staged by the Black Swan Theatre Company in Perth in 2012.

- Australian Dance Awards 2014

The long list of nominations for the 2014 Australian Dance Awards was released during April. From a Canberra perspective it is good to see a number of nominations with strong Canberra connections, although I wonder whether any or many of them will make the short lists given the fact that so few people outside Canberra will have seen the productions in the flesh. That concern aside, however, I was especially pleased to see Garry Stewart’s Monument on the list for two awards, an individual award to Stewart for outstanding achievement in choreography and an award to the Australian Ballet for outstanding performance by a company. It was also gratifying to see Life is a Work of Art created by Liz Lea and others for GOLD, the group of mature age performers associated with Canberra Dance Theatre, nominated in the community dance category.

But I noticed that Janet Karin, former director of the National Capital Ballet School, currently kinetic educator at the Australian Ballet School, and also now president of the International Association for Dance Medicine & Science, is again on the list for services to dance education. Fingers crossed for this one as her contribution to the Australian dance scene has been remarkable over many years and in many areas and she deserves recognition from her peers.

- Island: James Batchelor

I am looking forward to the opening of James Batchelor’s new work, Island, which premieres tonight at the Courtyard Theatre, Canberra Theatre Centre. Batchelor was impressive when I interviewed him earlier his month (see online link below) but seeing in production what one has written about in advance is always challenging. But Canberra needs more dance of the sophisticated variety. So fingers crossed!

- Press for April 2014 (Online links no longer available)

‘Outstanding skills shown in diversity’. Review of Sydney Dance Company’s Interplay. The Canberra Times, 12 April 2014, ARTS 19.

‘Dedicated Batchelor’. Preview story for James Batchelor’s Island. The Canberra Times, 26 April 2014.

Michelle Potter, 30 April 2014

Featured image: Ballet Rambert enjoying the Australian bush, 1948. From the personal album of Pamela Whittaker (Vincent)