- Hannah O’Neill

Admirers of Hannah O’Neill, and there are many if my web statistics are anything to go by, may be interested to read the following post on Laura Capelle’s website Bella Figura. In addition to what is written on the site, there is a link to an article written by Capelle for the American dance magazine Pointe. The article was published in the February/March issue of Pointe and Capelle has done a great job in getting O’Neill to open up about her experiences, including some of the difficulties she has faced in Paris.

UPDATE August 2020: The Bella figura website seems not to be available these days and I have removed the non-operational link. I did find, however, a Laura Capelle article about Hannah O’Neill at this link.

- Bodenwieser update

A news story on the Bodenwieser project being led by Jochen Roller, which I mentioned in last month’s dance diary, was screened on SBS TV a few days ago. The SBS story is available below.

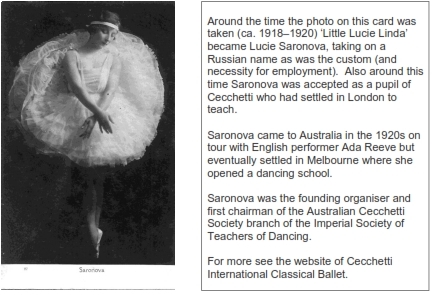

Below I have reproduced a photo of Marie Cuckson, who with Emmy Taussig assembled the Bodenwieser archival material and kept it in good order until she donated it to the National Library and the National Film and Sound Archive in 1998. The acquisition was part of the Keep Dancing! project, which was the forerunner to Australia Dancing. Marie Cuckson is seen in her home in Sydney in August 1998 with the material packaged and ready to be transported to Canberra.

- Oral history collections

As a result of the Athol Willoughby interview conducted recently I retrieved the listing of dance-related oral histories in the National Library and the National Film and Sound Archive that used to be part of Australia Dancing. I have updated that list (an old version is on the PANDORA Archive). Here is the link to the updated version. It is a remarkable list of resources going back to the 1960s with early recordings by pioneer oral historian Hazel de Berg and, in the case of the NFSA, to the 1950s with some radio interviews from that period. It includes, for example, interviews with every artistic director of the Australian Ballet—Peggy van Praagh, Robert Helpmann, Anne Woolliams, Marilyn Jones, Maina Gielgud, Ross Stretton and David McAllister—and with three of the company’s administrators/general managers—Geoffrey Ingram, Noël Pelly and Ian McRae. But it is not limited by any means to ballet and in fact covers most genres of dance and the ancillary arts as well.

That material held by the National Film and Sound Archive is included reflects the origins of the list, which was begun in the early days of the Australia Dancing project when the NFSA was a partner in the project (and in fact the major collecting partner in its initial stages). I have also posted the list on the Resources page of this website and will update it periodically as information about new interviews comes to light. It deserves to be more obvious than it is now—that is hidden in PANDORA in an outdated version—especially as it is not a static resource.

- Site news

February saw a huge jump in visits from France due largely to the post on the Paris Opera Ballet’s production of Giselle, which was the most accessed post during February by a runaway margin. Critics in France were curious about the reaction of Australian audiences and critics.

Coming in at fourth spot was a much older post on the Paris Opera Ballet’s production of Jiri Kylian’s Kaguyahime, which was having a return season in Paris in February. Interest in these two posts saw Paris become the fourth most active city after Sydney, Melbourne and Canberra.

The second most accessed post in February was an even older one, my review of Meryl Tankard’s Oracle, originally posted in 2009. Tankard is currently touring this work in the United States. At third spot was a post on Pina Bausch’s Rite of Spring perhaps reflecting the wide interest in 2013 in the many dance activities associated with the 100th anniversary of the first performance of the Stravinsky/Roerich/Nijinsky Rite of Spring, of which the Tankard tour is one.

Michelle Potter, 28 February 2013