Rachel Cameron Parker, dancer and dance teacher who has died in London just a few weeks short of her 87th birthday, worked all her life to maintain the classical basis of ballet.

On a trip to Australia in 1976 Cameron told oral historian Hazel de Berg:

‘I want the pure classical basis of the ballet to continue. I want it to continue in England, the whole of Europe, America, and Australia, so that we can extend and continue to build on this basis. I feel that out of 200 pupils maybe only one will grasp the real significance of this basic work. But out of 200 or 300, one person is enough for it to be handed down to future generations. I don’t want it to be lost.’

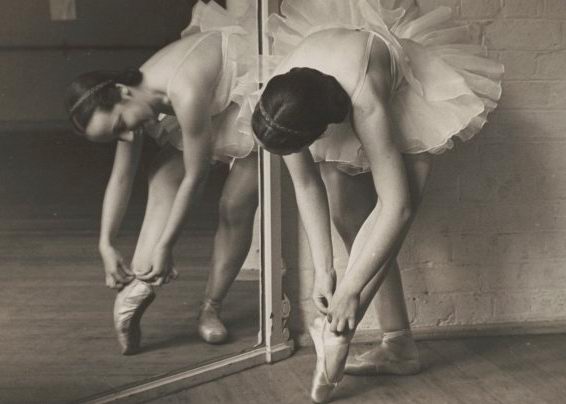

Cameron was born in Brisbane but spent her early childhood in Townsville in northern Queensland before moving to Sydney aged about 5 or 6. In Sydney she began dancing lessons with Muriel Sievers who had studied in London with Phyllis Bedells and who taught the syllabus of the Royal Academy of Dancing, as it was then called. It was with Sievers that Cameron first began teaching as Sievers quickly had her helping teach the youngest classes on Saturday morning. Sievers also insisted that Cameron take piano lessons and also lent her Tamara Karsavina’s book Theatre Street.

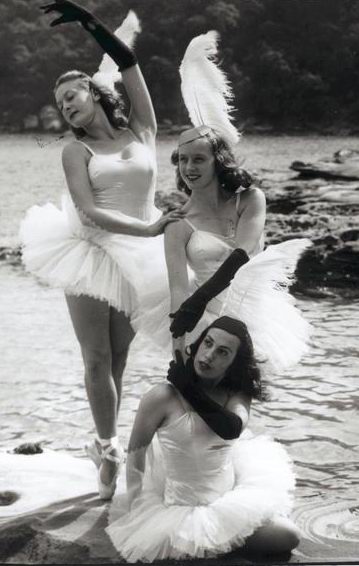

In the early 1940s Cameron danced with the Borovansky Australian Ballet Company, which later became the professional Borovansky Ballet and then with the Kirsova Ballet in Sydney, a company led by former star of the Monte Carlo Russian Ballet, Hélène Kirsova. There were also opportunities for Cameron to develop her teaching skills in Kirsova’s school, which was firmly grounded in what Kirsova referred to as the ‘Russian method’.

Cameron was given major roles in a number of Kirsova’s works including Revolution of the Umbrellas, Faust, A Dream…and a Fairy Tale, Harlequin, and Hansel and Gretel. She has recalled that her happiest days as a dancer were with Kirsova:

‘She was a woman who tried to mould her company in the Diaghilev tradition where music, the scenery, the dancers became part of one whole, and there it was I think that the true beginnings of Australian ballet lie.’

Moving to England with her husband Keith Parker, Cameron danced in Song of Norway and in a company directed by Molly Lake. She also studied in Paris with former stars of the Russian Imperial Ballet, Lubov Egorova and Olga Preobrajenska, and with many notable English teachers including Anna Northcote.

By her own admission one of the most exciting periods of her life came when she was asked to demonstrate for two great teachers and former ballerinas—Lydia Sokolova and Tamara Karsavina. With Karsavina she also developed a teaching syllabus for the Royal Academy of Dance.

‘Sokolova was absolutely marvellous,’ Cameron once recalled. ‘She was not content with near being good enough, it had to be exact or else.’

Of Karasavina, she has recalled: ‘I found for the first time that what I had always dreamed of was true, and that’s why, now, I am such a stickler for perfection of technique.’

Cameron was guest teacher for many companies around the world including the Australian Ballet. In December 2010 she was awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Award for a lifetime of services to dance. Rachel Cameron is survived by her brother Alister and nieces Alison, Fiona and Christine.

Rachel Cameron Parker: born 27 March 1924, died 6 March 2011

Michelle Potter, 13 April 2011

Postscript: One of the images of Cameron that has fascinated me, as much for its 1940s glamour as anything else, is that of her with her colleagues from the Kirsova Ballet, Peggy Sager and Strelsa Heckelman, posing outdoors at Taylor’s Bay close to Kirsova’s home on the northern shores of Sydney Harbour.

Added 28 April 2011: Maina Gielgud studied with Rachel Cameron at various points in her life and they remained close friends until the end of Rachel’s life. Maina shared this recollection:

Memories of Rachel from when she gave me private lessons when I was nine years old: Passionate, outspoken, knowledgeable. I believe she was an excellent dancer with lots of personality and mammoth technique.

I always remember her coming to see me in Newcastle (UK) performing Swan Lake with Festival Ballet. I thought I was dancing quite well (for once!)—she said nothing, but wrote me a long letter which quite disillusioned me, but certainly made me rethink what I was up to and how I went about my work and my dancing…

She knew I knew that she only bothered because she thought I was worth it…