This month’s dance diary has an eclectic mix of news about dance from across the globe. I am beginning with a cry for help from a New Zealand initiative, Ballet Collective Aotearoa, led by Turid Revfeim, dancer, teacher, coach, mentor, director across many dance organisations. I am moved to do this as a result of two crowd funding projects I initiated when I was in a similar position and needed an injection of funds to help with the production of my recent Kristian Fredrikson book. I was overwhelmed by the generosity of the arts community. It made such a difference to what my book looked like and I will forever be grateful.

- Ballet Collective Aotearoa

Ballet Collective Aotearoa was unsuccessful in its application to Creative New Zealand for funding to take its project, Subtle Dances, to Auckland and Dunedin in early 2021. The group has secured performances at the arts festivals at those two New Zealand cities. BCA’s line-up for Subtle Dances brings together a great mix of experienced professional dancers and recent graduates from the New Zealand School of Dance. They will perform new works by Cameron McMillan, Loughlan Prior and Sarah Knox.

For my Australia readers, Prior has strong Australian connections, having been born in Melbourne and educated at the Victorian College of the Arts Secondary School. Then, Cameron McMillan, a New Zealander by birth, trained at the Australian Ballet School and has danced with Australian Dance Theatre and Sydney Dance Company. And, dancing in the program will be William Fitzgerald who was brought up in Canberra, attended Radford College and has been a guest dance teacher there, and studied dance in Canberra with Kim Harvey.

The campaign to raise money for Turid Revfeim’s exceptional venture is via the New Zealand organisation, Boosted. See this link to contribute. See more on the BCA website.

- Interconnect. Liz Lea Productions

Liz Lea’s Interconnect was presented as part of the annual DESIGN Canberra Festival and focused on connections between India and Canberra. The idea took inspiration from the designers of the city of Canberra, Walter Burley and Marion Mahoney Griffin, and from the fact that Walter Burley Griffin spent his last years in India where he died in Lucknow in 1937. As a result, the program featured a cross section of dance styles from Apsaras Arts Canberra, the Sadhanalaya School of Arts and several exponents of Western contemporary styles.

Interconnect was shown at Gorman Arts Centre in a space that was previously an art gallery. Physical distancing was observed, as we have come to expect. I enjoyed the through-line of humour that Lea is able to inject into all her works, including Interconnect. I was also taken by a short interlude called Connect in which Lea danced to live music played on electric guitar by Shane Hogan, and which featured on film in the background a line drawing of changing patterns created by Andrea McCuaig. Multiple connections there!

- Gray Veredon

Choreographer Gray Veredon has put together a new website set out in several parts under the headings ‘The Challenge’, ‘New Ways in Set Design’, and ‘Influences and Masters’. His themes are developed using as background his recent work in Poland, A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Gray Veredon’s website can be viewed at this link.

- Jean Stewart

Jean Stewart, whose dance photographs I have used many times on this website, is the subject of a short video put together by the State Library of Victoria. Jean died in 2017 and donated her archive to the SLV. Here is the link to video. And below are two of my favourite photographs from other sources. I can’t get over the costumes in the background of the Coppélia shot! Is that Act II?

Other Stewart favourites appear in the brief tribute I wrote back in 2017.

- Jacob’s Pillow fire

Devastating and heartbreaking news came from Jacob’s Pillow during November. Its Doris Duke Theatre was burnt to the ground.

Here is a link to the report from the Pillow.

- Nina Popova (1922-2020)

Nina Popova, Russian born dancer who danced in Australia during the third Ballets Russes tour in 1939-1940, died in Florida in August 2020. I was especially saddened to learn that her death was a result of COVID-19.

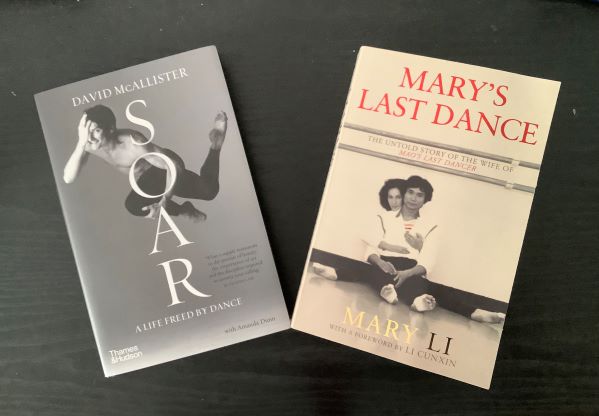

- Kristian Fredrikson. Designer. More comments and reviews

Kristian Fredrikson. Designer was ‘Highly Recommended’ on the Summer Reading Guide in its ‘Biography’ category.

Mention of it also appeared on the Australian Ballet’s site, Behind Ballet, Issue # 252 of 18 November 2020 with the following text:

KRISTIAN FREDRIKSON, DESIGNER A lavish new book by historian and curator Michelle Potter takes us inside the fascinating world of Fredrikson, whose rich and inventive designs grace so many of our productions. MORE INFO

I was also thrilled to receive just recently a message from Amitava Sarkar, whose photographs from Stanton Welch’s Pecos and Swan Lake for Houston Ballet are a magnificent addition to the book. He wrote: ‘Congratulations. What a worthwhile project in this area of minimal research.‘ He is absolutely right that design for the stage is an area of minimal research! Let’s hope it doesn’t always remain that way.

Michelle Potter, 30 November 2020

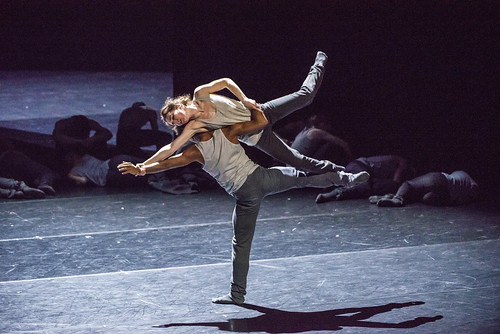

Featured image: Abigail Boyle and William Fitzgerald in a promotional image for Subtle Dances, Ballet Collective Aoteaora, 2020. Photo: © Celia Walmsley, Stagebox Photography