The Age of Unbeauty goes back to 2002 when, as a work in progress. it was performed at the Adelaide Fringe. After that it played across Australia and around the world and won a number of awards. I am not sure of the date of the performance that was streamed as part of ADAPT, and by the time I thought to try to find out the streaming had closed. I’m not sure that it was ever revealed in the closing credits anyway

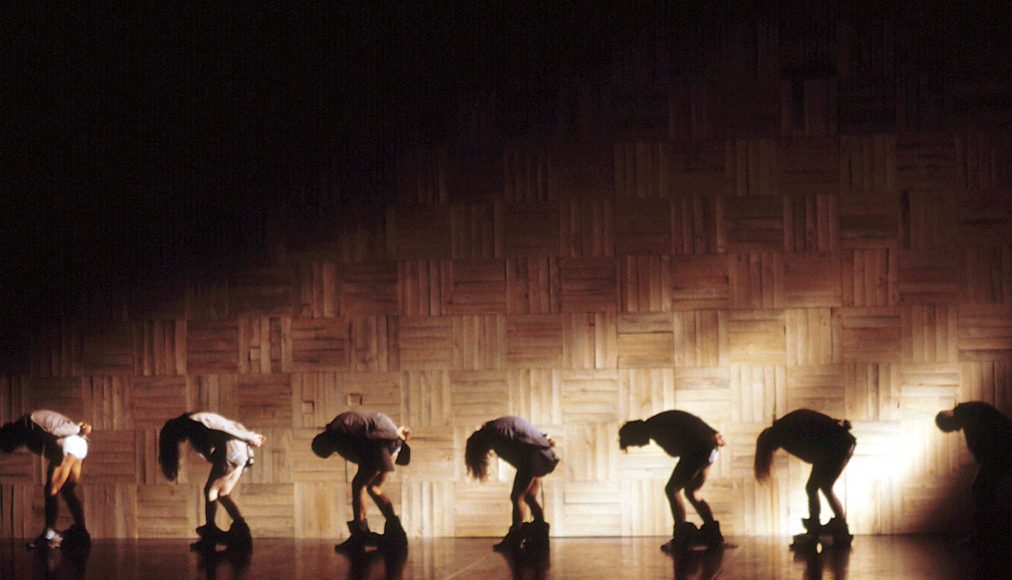

I hadn’t seen The Age of Unbeauty before and several words came straight to mind as I watched: violence, hatred, cruelty, intimidation, shame, vulnerability—words like that. It dealt with man’s inhumanity to man and certainly the relationships between the characters were mostly inhumane, and related, or so I understand, to artistic director Garry Stewart’s thoughts on the horrific treatment of refugees. Choreographic violence was clear. The dropping of pants was a constant image. There were references to medical issues, to imprisonment, to abuse. And there was a heart-stopping moment when two naked figures were visible behind a glass door unable to get out.

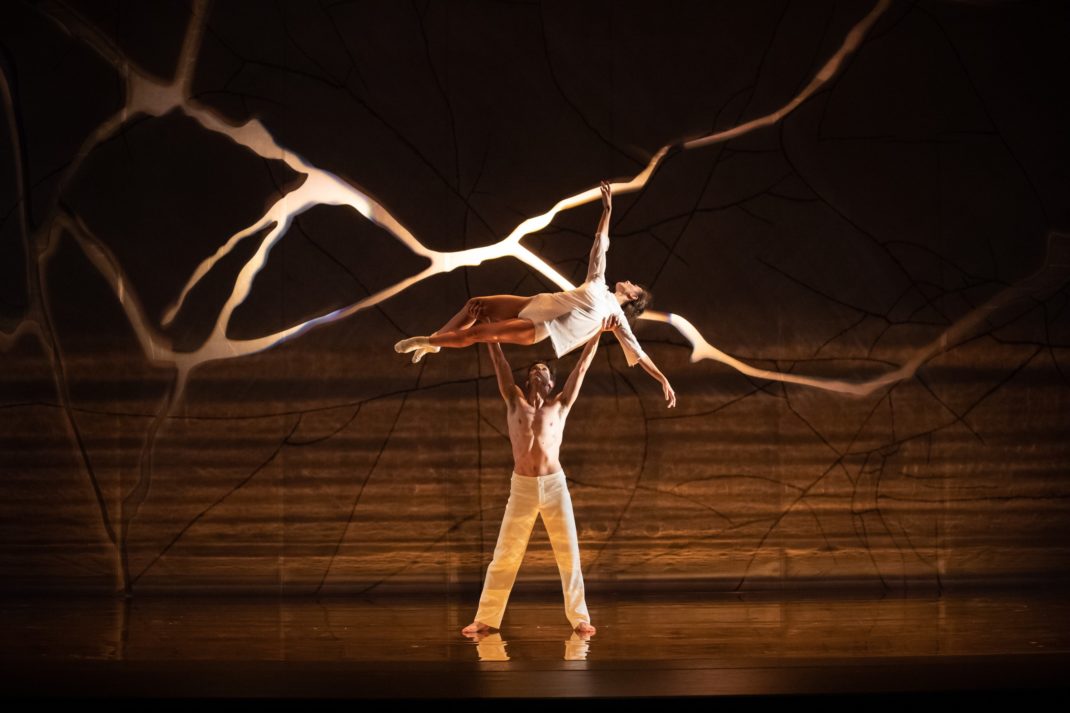

As we have come to expect from Australian Dance Theatre under Stewart’s direction, the performers were astonishing. Their gymnastic skills seem to know no bounds. They threw themselves through the air. They tumbled and turned. They balanced in positions that defy belief. But despite their incredible physical skills, somehow they are beginning to remind me of circus performers rather than dancers. It was, thus, with a sense of pleasure that I watched a quite beautiful video clip, the work of David Evans, towards the end of the work. In black and white, it consisted of individual headshots of men and women making simple, calm, unhurried moves. They turned their heads, or moved their gaze, nothing much more. Humanity at its most moving. Relief!

Michelle Potter, 13 July 2020

Featured image: Artists of Australian Dance Theatre in The Age of Unbeauty. Photo: © Alex Makayev