2 March 2019. 92Y, New York (Harkness Dance Festival 2019)

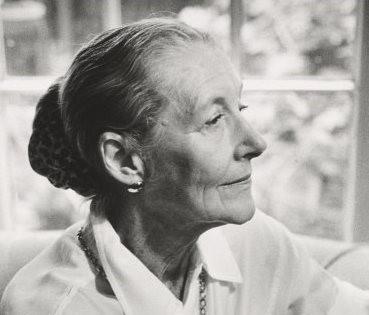

In 2019 the dance world is celebrating the centenary of the birth of Merce Cunningham with events across the globe. Most, not surprisingly, are being held throughout the United States. In Australia we had just one event, and I found it highly disappointing. So, it was a thrill to be in New York on a brief visit at a time when the 92nd St Y was holding a program (part of the 2019 Harkness Dance Festival) called A Feast of Cunningham. It was led by Sydney-born Melissa Toogood, a former dancer with Merce Cunningham Dance Company and a distinguished coach and teacher of Cunningham technique.

The program consisted of solos from Doubles (1984) and Loose Time (2002); Septet (1953); an excerpt from Scenario (1997); Cross Currents (1964); excerpts from Landrover (1972) and Trails (1982); and a Minevent. While all had their specific interest, for me it was Septet that gave the greatest pleasure. One of the very early works from Merce Cunningham Dance Company, which I had never seen before, it was fascinating to see choreography that had such an obvious link to the vocabulary and structure of ballet. The dancers used the upper body differently (with a bit more fluidity perhaps), and arms were more curved than is apparent in later works, with beautifully rounded fourth positions apparent at various times. I was also surprised to see one of the male dancers execute (very nicely I might add) a manѐge of turns and jumps. Quite balletic really.

While many of the dancers could be singled out for the particular qualities they exhibited, I found Melissa Toogood’s dancing exceptional. She appeared in several of the works and showed a great command of those features that characterise Cunningham technique, in particular a wonderful awareness of the space the body occupies when it moves (or takes a pose). When she faces front everything faces front, exactly. When she tilts her head to the side it goes exactly to the side, and so on. This exactness was missing from the young dancers from the New World School of the Arts who performed the Minevent that closed the program. While the enthusiasm was all there, in the end, without the exactness we saw from Toogood (and the other older, more experienced dancers), the Minevent looked a little messy to me. More rehearsal/class time needed?

***********************************M

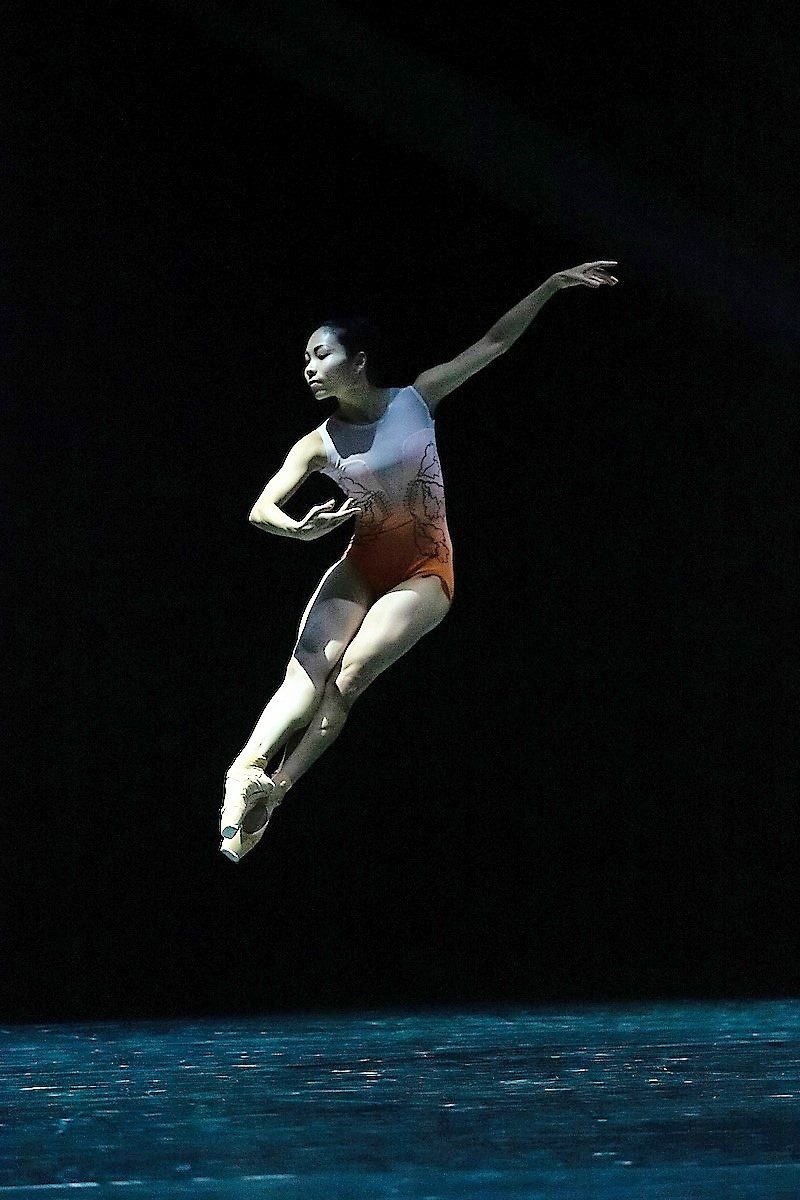

DIA Beacon Events (2009). Brandon Collwes of Merce Cunningham Dance Company. DIA Art Foundation, Beacon, New York. Dan Flavin Gallery, 20 February December 2009. Photo: © Stephanie Berger

Also on show at the 92Y was an exhibition of photographs, Merce Cunningham: Passing Time 1967-2011, Photos by James Klosty and Stephanie Berger. Klosty’s images date to the 1960s and 1970s and have long been seen as the standard go-to shots for that early era of Cunningham’s work. The exhibition included many of his classic shots, including portraits of Cunningham’s collaborators of the time such as, John Cage, David Tudor, Marcel Duchamp, Jasper Johns and others. Stephanie Berger’s images are quite different and their great strength is that they show clearly the nature of Cunningham vocabulary: the tilt of bodies, the strong sense of direction and spatial awareness, the extended limbs, the typical leaps and poses, and much more. Next to Berger’s shots, Klosty’s images have a kind of mystery and an emotive quality. Berger, on the other hand, gives us a fresh and exciting look at Cunningham’s work, and her images have their own emotional appeal. The work of both photographers benefits from this joint display.

Both images used in this post are from Merce Cunningham: Passing Time 1967-2011, Photos by James Klosty and Stephanie Berger and are used with the kind permission of the photographer.

Michelle Potter, 5 March 2019

Featured image: DIA Beacon Events (2008). Merce Cunningham Dance Company. DIA Art Foundation, Beacon, New York. Riggio Galleries, 5 December 2008. Photo: © Stephanie Berger