Mixed in with old faithfuls like Swan Lake and Coppélia, the Australian Ballet’s program for 2016 contains one or two works that we can anticipate with a bit of excitement. One of them is John Neumeier’s Nijinsky, which will be seen in Melbourne, Adelaide and Sydney, although we will have to wait until the last few months of the year.

Nijinsky was created in 2000 for Neumeier’s Hamburg Ballet and was seen recently in Australia when Hamburg Ballet performed it in Brisbane in 2012. On that occasion it received a standing ovation on its opening night—and I mean a real standing ovation where the theatre rose as one. No stragglers, no people leaving to catch the subway before the rush, no one standing up because they couldn’t see what was happening because the person in the row in front was blocking their view. A proper standing ovation. Neumeier calls Nijinsky ‘a biography of the soul, of feelings, emotions, and of states of mind’. It needs wonderful dancing, and fabulous acting. My fingers are crossed. Here is what I wrote about it from Brisbane.

Another program that fills me with anticipation is a triple bill called Vitesse presenting works by Christopher Wheeldon (DGV: Danse à grande vitesse), Jiri Kylian (Forgotten Land) and William Forsythe (In the Middle, Somewhat Elevated). It is scheduled for the early part of the year and will be seen in Melbourne and Sydney.

Forgotten Land and In the Middle are not new to the Australian Ballet repertoire having been introduced during Maina Gielgud’s artistic directorship. I remember watching people leave the auditorium after the opening sounds of Thom Willems score for In the Middle (it was 20 years ago), but it showed off certain dancers of that era absolutely brilliantly. But the Wheeldon is new to Australia. It is a work for 26 dancers with four pairs of dancers at the heart of the work. It shows in particular Wheeldon’s skill at creating pas de deux. In the Royal Ballet program notes from its showing in 2011, Roslyn Sulcas writes of Wheeldon that ‘[He]—like his ballets—is both traditional and innovative, able to inhabit an older world while moving firmly forward towards the new.’ Here is what I wrote after seeing it, on a very different mixed bill program, in London in 2011.

Then I await Stanton Welch’s Romeo and Juliet, exclusive to Melbourne in June and July, with anticipation mixed with trepidation. I was not a fan of his Bayadère, although I have loved some of his shorter works. But the word is that his R & J is ‘quite good’. Fingers crossed again.

As for the rest of the year, Brisbane will get Ratmansky’s Cinderella in February; Stephen Baynes’ Swan Lake returns with seasons in Sydney, Adelaide and Melbourne; a program called Symphony in C will run concurrently in Sydney with the Vitesse program, although it is not exactly clear as yet of what the Symphony in C program will consist; and Coppélia will be in Sydney and Melbourne towards the end of the year. I think this is the Peggy van Praagh/George Ogilvie production from 1979, but the media release is a little confusing. ‘Having first revisited Coppélia in 1979, the great choreographer re-invigorated it thirty years later with this joyful and sumptuous production.’ Who is that great choreographer? Not PVP who was not really the choreographer and who died anyway in 1990.

And for my Canberra readers, we won’t be seeing the Australian Ballet in 2016 in the national capital where we too pay taxes.

Michelle Potter, 23 September 2015

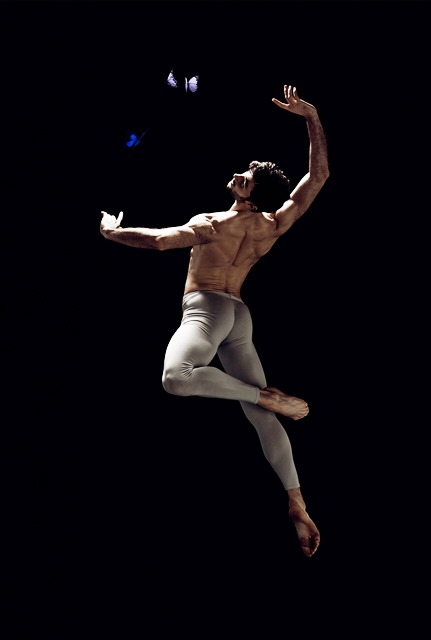

Featured image: Dancer of the Australian Ballet in costume for Coppélia, 2015 (detail). Photo: © Justin Ridler

- Full details of the 2016 season are on the Australian Ballet’s website.