15 November 2023 (matinee). Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House

This double bill of works by Frederick Ashton was an entertaining two hours of ballet. I enjoyed in particular the opening work, Marguerite and Armand, for its episodic structure that gave a strong focus to specific moments of love between Marguerite and Armand, and later the moment of Marguerite’s death from tuberculosis. I enjoyed too the minimal set and its semi-circular nature (design Cecil Beaton) that went well with the general structure of the work.

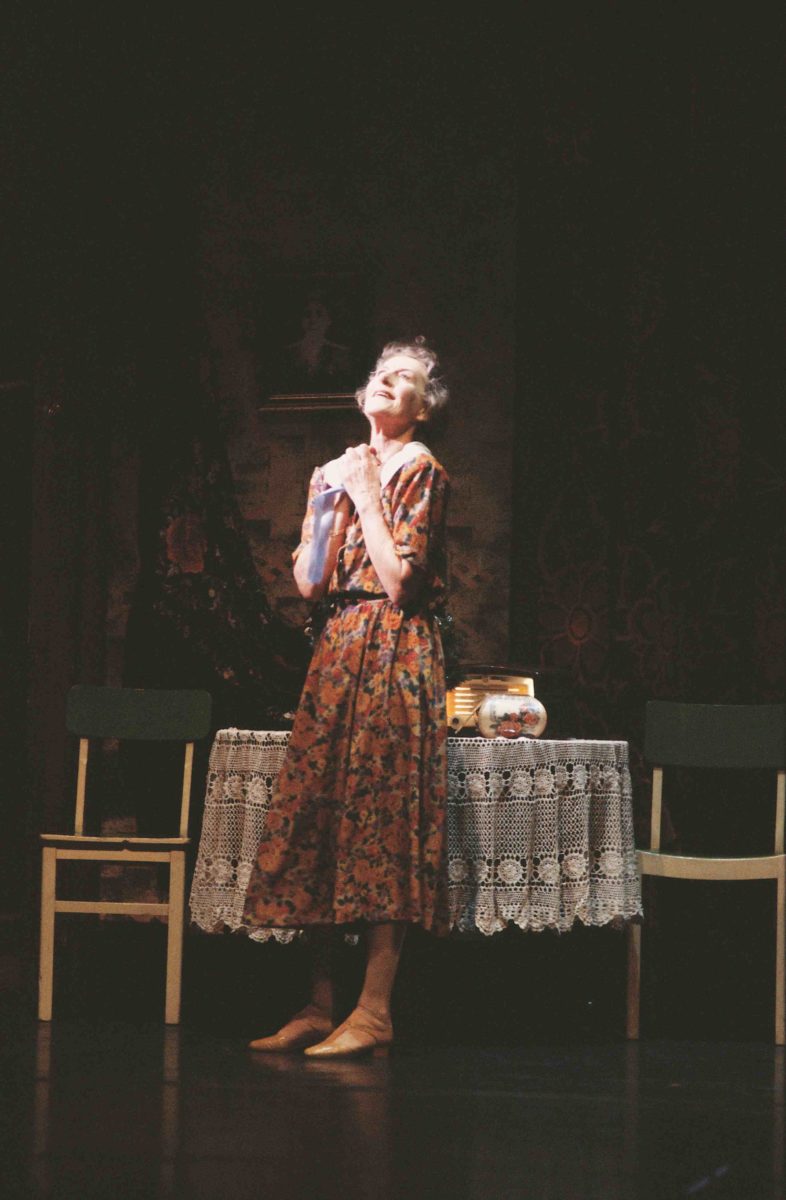

Valerie Tereschenko danced nicely as Marguerite and made her characterisation reasonably clear. But Maxim Zenin as Armand didn’t offer quite enough of Armand’s emotional state to make his character stand out. So the partnership was not as powerful as it needs to be in this work.

Unfortunately (or fortunately for me), I clearly remember Sylvie Guillem dancing the female lead in Marguerite and Armand in Sydney and Melbourne way back in 2002 when the Royal Ballet, then under the direction of Ross Stretton, visited from London.* More recently (2018) I also saw Alessandra Ferri and Federico Bonelli give a stunning performance with the Royal Ballet in London. So I had high expectations, which I’m sad to say weren’t met. I get the feeling that the Australia Ballet currently concentrates more on technical action at the expense of the need for a powerful dramatic essence.

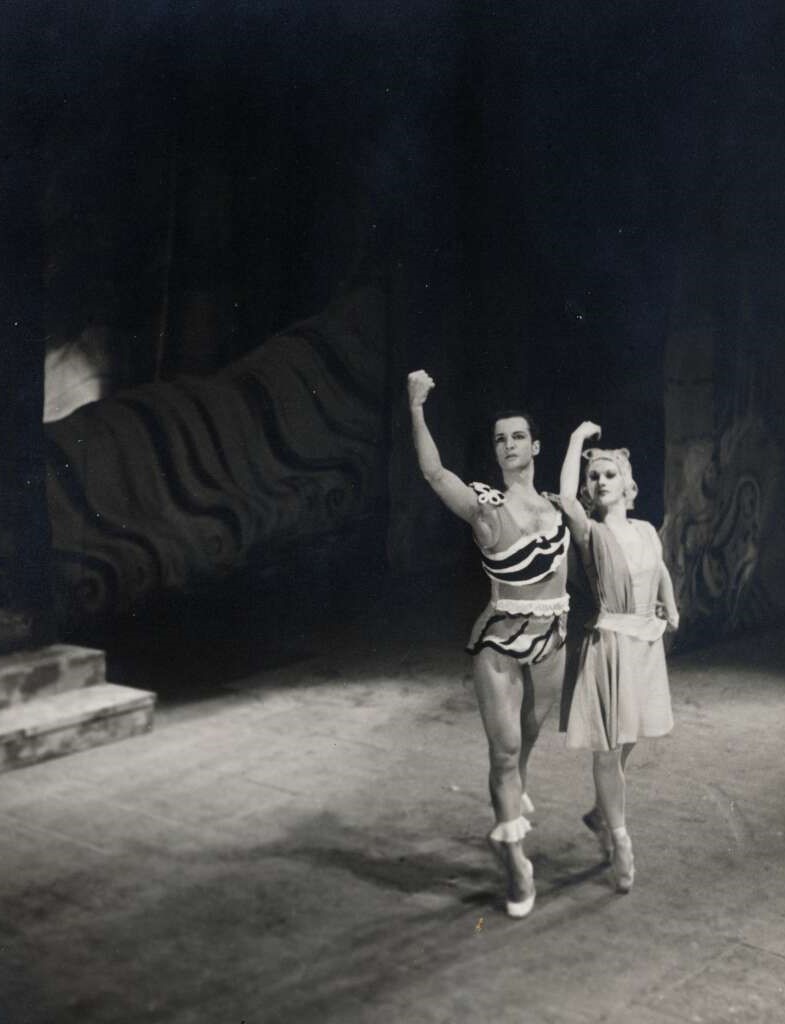

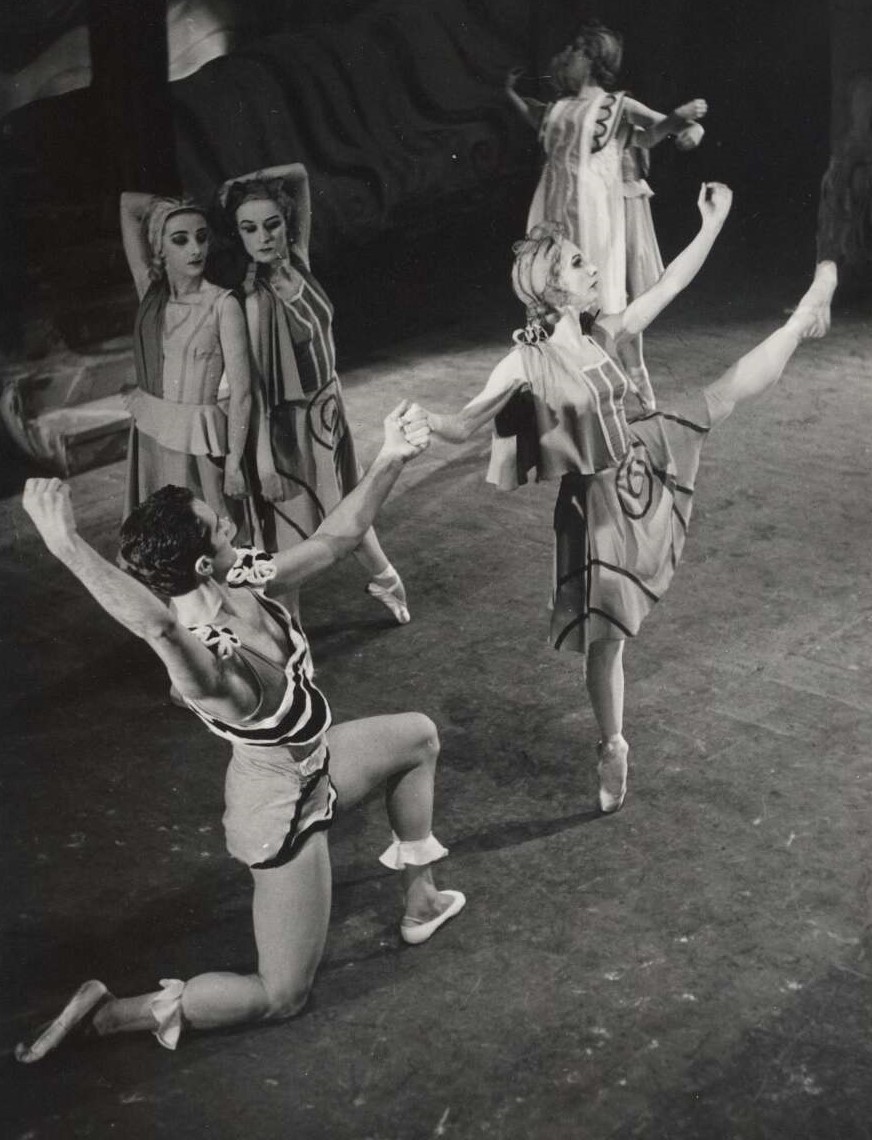

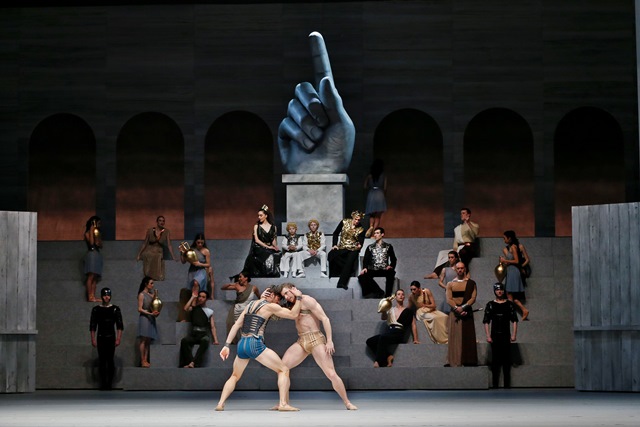

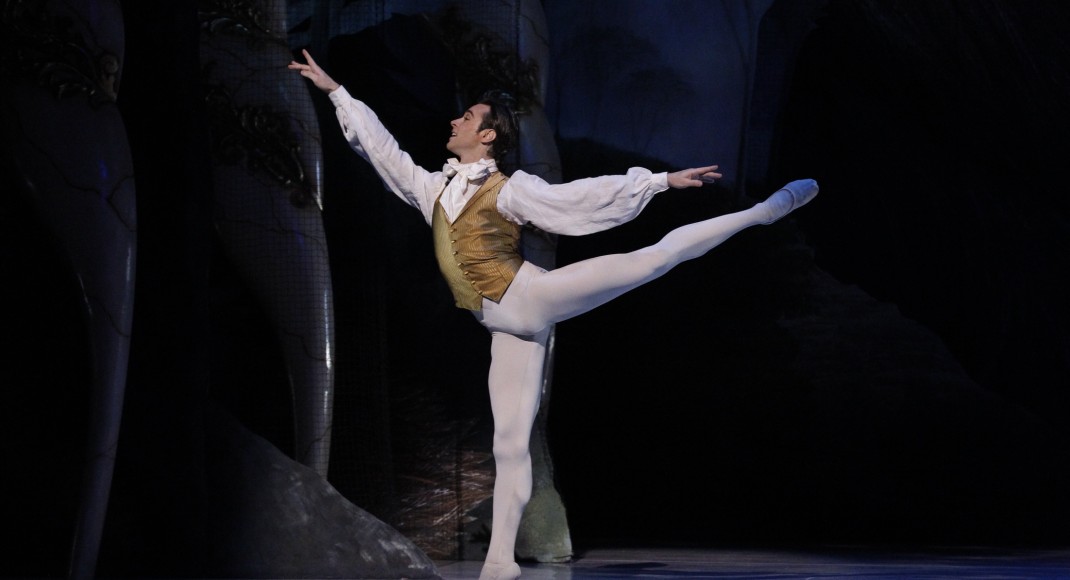

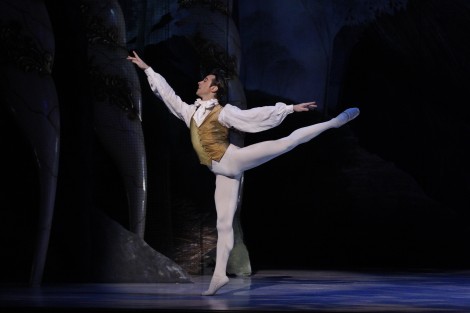

As for A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Bendicte Bemet as Titania and Joseph Caley as Oberon danced well but again I felt they lacked strength of characterisation. Were they King and Queen? Did they rule over the Fairies? Were they really arguing over the Changeling? And so on.

Of the other characters, Bottom (Luke Marchant) dancing on pointe is always a highlight in the Ashton production and Marchant looked very comfortable as he hopped and skipped around on pointe. But again he needed stronger characterisation, especially after he had returned to his role as a Rustic and tried to remember what had happened while under the spell cast on him by Puck.

Unfortunately (again) in terms of how I saw the Ashton production and the Australian Ballet’s performance of it, I had just seen Liam Scarlett’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream performed by Queensland Ballet. Scarlett’s take on the story has so much more to offer than does the Ashton production. And in performing it the dancers of Queensland Ballet demonstrated not only their truly exceptional technical and production values but also the manner in which they have been coached to inhabit a role. It was completely engaging rather than simply entertaining.

While I can say the Australian Ballet’s season of the two Ashton works was entertaining, it did leave me a little cold. I hope there might be more focus soon on dramatic and emotional input. Please!

Michelle Potter, 16 November 2023.

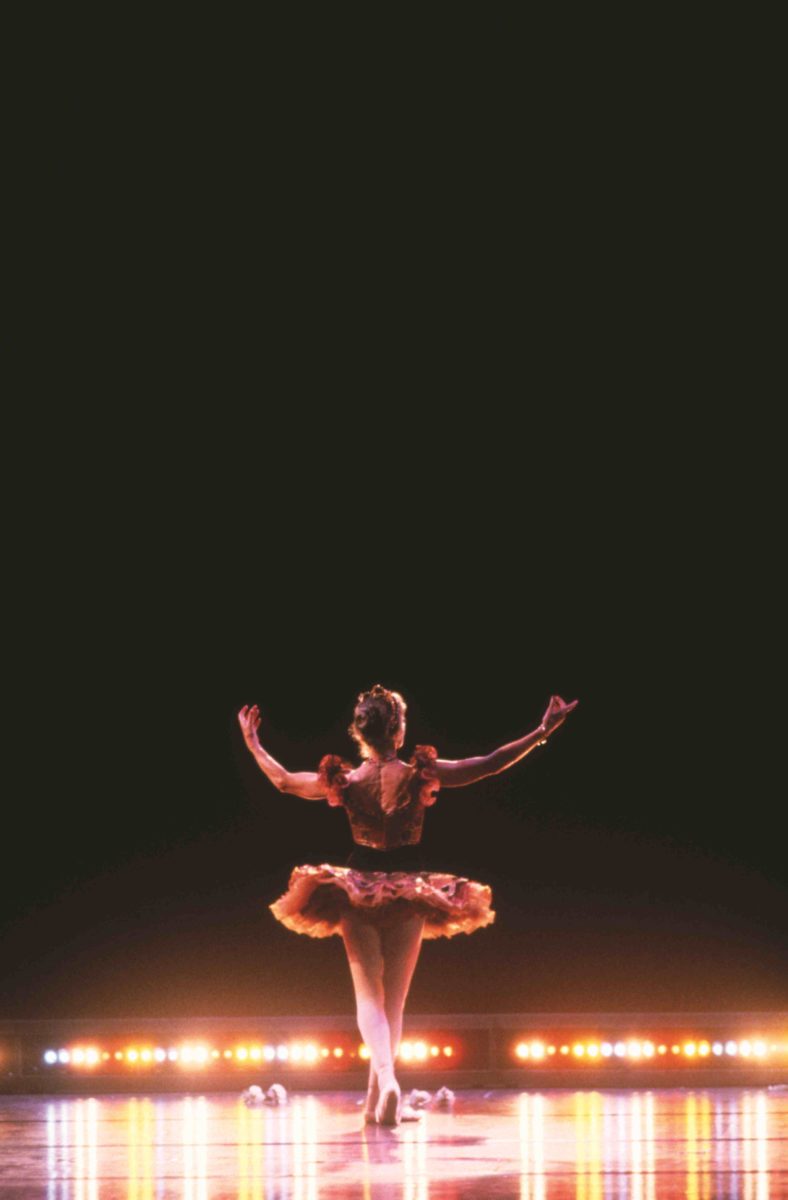

Featured image: Artists of the Australian Ballet in The Dream, 2023. Photo © Daniel Boud

*The Australian Ballet’s website mentions that Marguerite and Armand is having its premiere season in Australia. It might be the premiere for the Australian Ballet, but it’s not the premiere for Australia, the country.