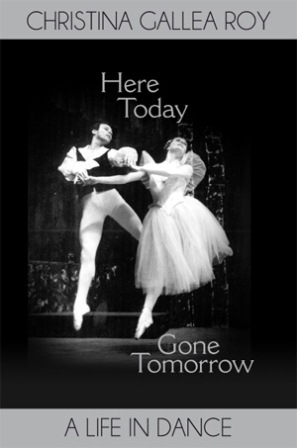

My copy of Christina Gallea Roy’s book Here today, gone tomorrow has an inscription on the fly leaf that reads in part ‘Here is the rest of the story!’ I first had contact with Gallea when she donated to the National Library in Canberra a collection of material relating to her early career as a dancer with Walter Gore’s and Paul Hinton’s company, Australian Theatre Ballet. And there is indeed a whole lot more to the story.

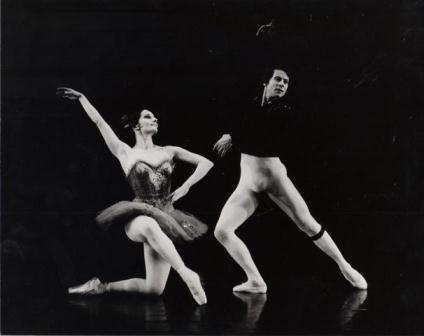

Christina Gallea and Alexander Roy came from very different dance backgrounds. She was Sydney girl and studied at the Frances Scully School of Dancing; her first professional engagement was as a dancer with the Gore/Hinton Australian Theatre Ballet in 1955. He came from Magdeburg and danced with the ballet company at the Komische Oper in East Berlin. They met as members of American Festival Ballet, with which they toured Europe, and married in the 1960s. Their dance training and early careers are discussed briefly in the opening sections of the book. These sections set the scene for an account of the more than thirty years they spent leading an independent ballet company, International Ballet Caravan,* later Alexander Roy London Ballet Theatre.

Those early sections of the book provide glimpses of some of the teachers and choreographers with whom they worked. From an Australian perspective, Gallea’s ongoing friendship and working relationship with Gore and Hinton have resulted in some insightful comments on these two artists. In addition to their work in 1955 with Australian Theatre Ballet, Gore and Hinton were in Australia with Ballet Rambert in the 1940s. However, very little has been written about their contribution to Australian dance so Gallea’s comments are more than welcome. But from a wider perspective Gallea also brings to life many others in the dance world who were working in London and Paris in the 1960s including teachers Audrey De Vos and Nora Kiss (Madame Nora), choreographer Léonide Massine and dancer and teacher Rosella Hightower.

The bulk of the book though records their life on the road travelling up and down England, across Europe, in Asia and through the Americas. It is an astonishing and absorbing story and full of marvellous, often hilarious anecdotes. Their repertoire was broad and largely original. Much of it was choreographed by Roy. Towards the end of the book Gallea writes: ‘We had given ourselves an outlet for almost unhindered creation, sometimes experimentation, and in doing this formed our own very individual style’. Their determination and their dedication to working independently seemed to know no bounds.

But what I found so arresting about the book was Gallea’s strong visual sensibility and her capacity to translate that sensibility into words. There’s her description of Paris in the 1960s: the cafes, the metro, the pissoirs, the clochards, the smells of ‘garlic, red wine and body odour’, the apartments with their unusual bathroom facilities. And her writing about food, as in her description of a meal taken in the Auvergne region of France ‘…boeuf en daube, made with the rich dark meat of the Camargue cattle which had marinated for a day in the equally rich and dark wine of the Languedoc…’. There are some evocative accounts of outdoor performances around the world and descriptions of theatres in various locations—in Quito, Ecuador, for example, where the auditorium held 4,000 people and sat in Gallea’s eyes ‘somewhere between a baroque cathedral and a 1930s movie palace’. And of course there are many stories about difficulties with accommodation, venues, transport, lighting rigs, contracts, collecting payment and so on.

This is not an academic book. Its subtitle is ‘A life in dance’ and that’s exactly what the book is about—a life spent dancing with all its problems and pleasures. Gallea writes as a kind of summary, ‘It had been an extraordinary adventure, foolhardy, no doubt, and if the workload had often been unbearable, the rewards had been many.’ It is so easy to live that adventure vicariously through the pages of this book. I haven’t enjoyed a dance book so much for a long time.

Michelle Potter, 12 July 2012

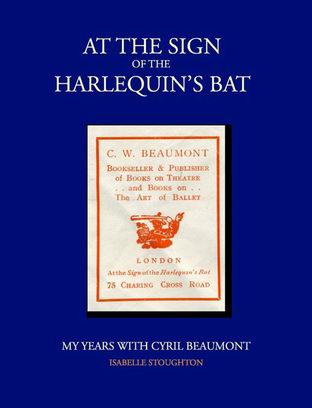

Christina Gallea Roy, Here today, gone tomorrow: a life in dance (Sussex: Book Guild Publishing, 2012)

Hardback, 338 pp. ISBN 978-1-84624-690-6

RRP £17.99. Available through many online sites.

*There is a kind of Australian bonus in the accounts of International Ballet Caravan. Graeme Murphy and Janet Vernon performed with the company briefly in the 1970s. Here today, gone tomorrow thus provides background for the early years of the Murphy/Vernon story.