30 & 31 August 2018, State Theatre, Victorian Arts Centre, Melbourne

Maina Gielgud’s Giselle, brought back once more by the Australian Ballet for a Melbourne only season, began beautifully—so beautifully that it gave me goose bumps. Small groups of villagers moved across the stage, interacting with each other, laughing and joking, while Orchestra Victoria, masterfully led by Simon Hewett, put us in the mood for what was to follow. It all seemed beautifully real rather than staged and distant. Much of this kind of interaction continued throughout with only a few moments where everyone stood around in a semi-circle of inactivity.

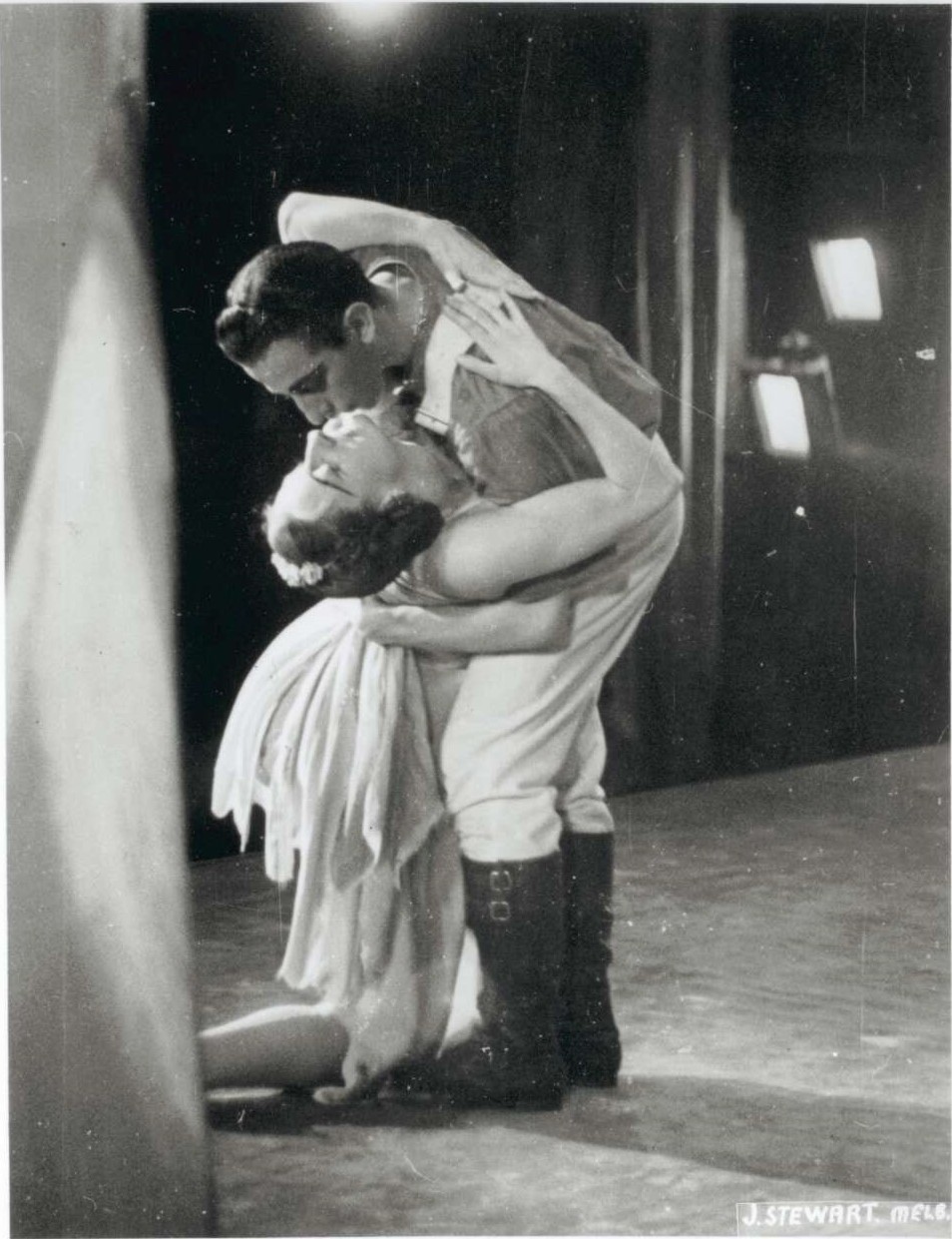

The opening night cast of Ako Kondo as Giselle and Ty King-Wall as Albrecht left me a little cold, although Kondo, who always dances superbly, was charmingly shy, perhaps even naive about what was happening to her. She needed a stronger Albrecht to give extra meaning to her portrayal. It takes two for the nature of any relationship to be seen and understood by an audience.

Andrew Killian did a sterling job as Hilarion and Lisa Bolte played Berthe as a motherly figure consumed by domesticity. I have, however, always imagined Berthe as a somewhat more feisty character, who is respectful towards the Duke (Steven Heathcote), Bathilde (Alice Topp) and their entourage, but who doesn’t behave obsequiously towards them. Perhaps the Duke was Giselle’s father? (This was an interpretation in the mind of Laurel Martyn and others and influences how Berthe encounters and interacts with the Duke and his party).

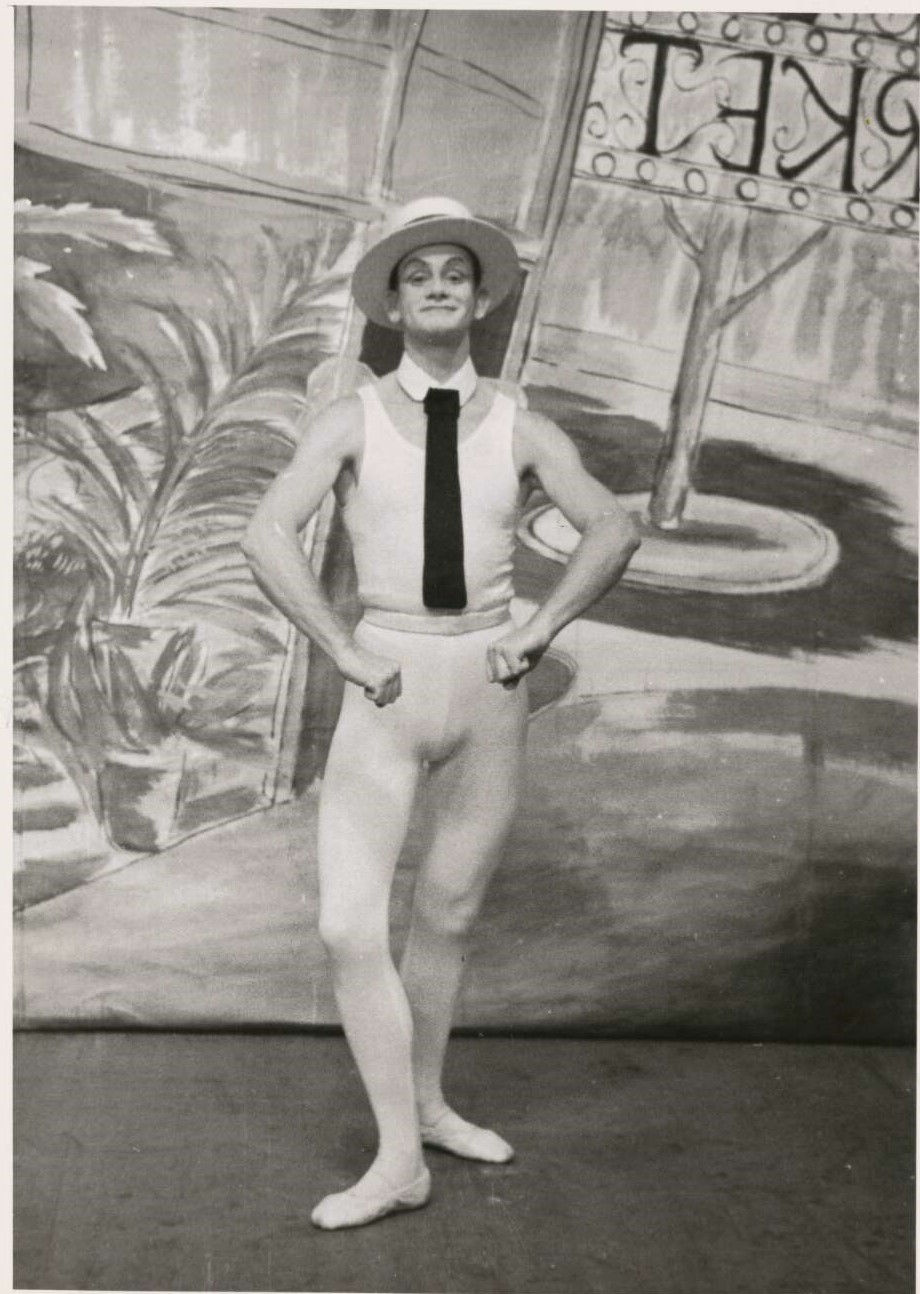

But the real stars of Act I on opening night were Brett Chynoweth and Jade Wood who danced the Peasant pas de deux. Chynoweth in particular danced spectacularly well with beautiful control and great placement at the end of those airborne tours. It was wonderful to watch him, too, when Wood was dancing her variations. There he was going from friend to friend telling them all how wonderful she was.

The mad scene was adequate, but that’s about it.

Act II on opening night also began beautifully with visions of Wilis appearing in the mist as Hilarion ran through the forest in search of Giselle’s grave. But I didn’t feel moved as events unfolded, due perhaps to an ongoing lack of strength in the relationship between Giselle and Albrecht. Valerie Tereshchenko as Myrtha had a fierce look on her face but her gestures and the way she attacked the choreography didn’t quite match the facial expression, which also lessened the emotional impact one expects from Act II.

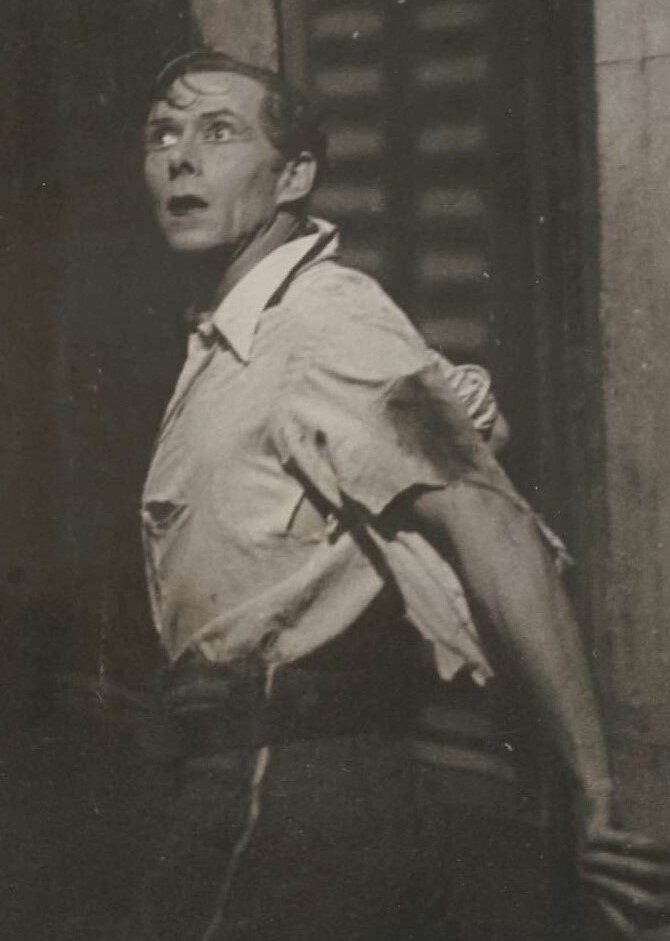

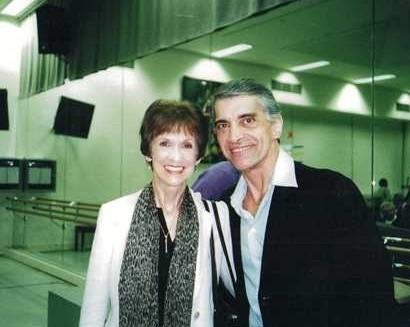

I was lucky, however, to be at the second performance in which Leanne Stojmenov as Giselle danced with David Hallberg as Albrecht. Act II this time was the stronger of the two acts, although it was interesting to see Stojmenov’s reading of Giselle in Act I as a somewhat less naive character, a little coy at times but certainly in it (to start with anyway) for the ride. This of course made her collapse, when she realised she had been betrayed, much stronger.

Hallberg and Stojmenov gave a moving performance in Act II. She had the right ethereal, supernatural touch, he could plead for mercy from Myrtha and make us feel for him. Their central pas de deux unfolded slowly and exquisitely before our eyes. Hallberg’s solo of entrechats six was spectacular from a technical point of view and yet he managed not to look like he was dancing in an eisteddfod. At last I felt emotionally involved, even from a distance since I was sitting in the gallery (aka the gods of former times). Amy Harris as Myrtha in this cast was forceful in her gestures and body language as a whole, and so she drove the action along nicely.

I often wonder to what extent the dancers of the Australian Ballet think about the nature of the characters they are portraying in ballets like Giselle. Do they wonder what goes on inside the minds of those characters? Do they wonder what kind of existence the characters might have beyond the immediate story? And so on. And do they then consider how to encapsulate that character in movement?

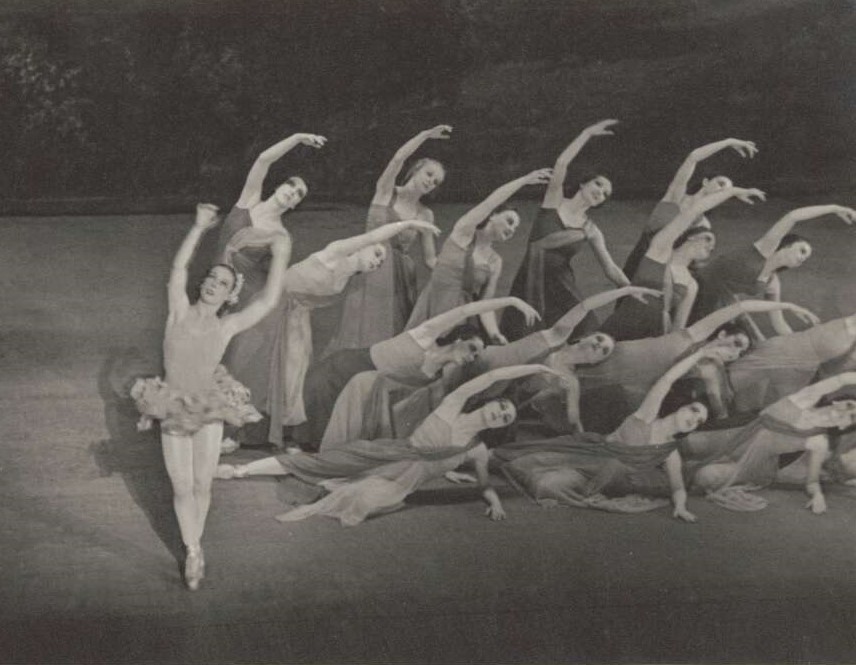

But there was a lot beyond interpretation of characters to admire about this production. The corps de ballet in Act I, for example, appeared to have had someone working with them on the use of head, arms and upper body. Fluidity of movement was thus more noticeable than usual. I also admired Hewett’s leadership of Orchestra Victoria. I felt I was listening not to a concert performance of the Adolphe Adam score, but to music to accompany the story as it was unfolding onstage. It was also an experience to sit high up in the auditorium. Apart from the fact that Stojmenov and Hallberg were able to project emotion the way they did right up into the gods, I have never been so aware before of the spatial patterns of the choreography for the corps de ballet.

To finish, there were two interesting happenings with regard to curtain calls. On opening night, minor principals who only appear in Act I joined the cast of Act II for a curtain call—not a usual occurrence. Then, following the second night’s performance, as Stojmenov and Hallberg moved downstage to take another bow together, the cast of Wilis behind them broke into applause—now that’s an accolade.

Michelle Potter, 1 September 2018

Featured mage: Ako Kondo and Ty King-Wall in Giselle Act I. The Australian Ballet, 2018. Photo: © Jeff Busby