This last triple bill of the Australian Ballet’s 2010 season was an opportunity to revisit two ballets created by resident choreographer Stephen Baynes and to ponder on the emergence of a new force in Australian choreography, Tim Harbour.

Edge of Night, which gave the program its name, was first seen in 1997. What especially stood out for me from this 2010 viewing was the visual strength of the work. Michael Pearce’s set and costumes and Stephen Wickham’s lighting evoked just the right atmosphere of nostalgia, longing and sad (and perhaps not so sad) memories. A real sense of collaboration was evident and Pearce in particular deserves many accolades for bringing a quality of surrealism to the design, which suggested the role of the subconscious in our most nostalgic encounters. Pianist Stuart Macklin added to the mood with his expressive playing of the seven Rachmaninov Preludes to which Edge of Night is set.

Kirsty Martin was elegant in the leading female role and the partnership with Robert Curran as the man in her past was as smooth as silk. But Martin played the part a little coldly for my liking missing the opportunity to develop an emotional connection with the audience. The stand-out performer was Laura Tong as the girl on the swing. She did connect with us and the youthfulness and the ‘breath of spring’ quality to her dancing was a joy.

Harbour’s new work, Halcyon, had a strong narrative line and suffered from being pretty much incomprehensible unless one knew intimately the Greek myth concerning the wind goddess Halcyon’s doomed love affair, and its consequences, with the mortal Ceyx. The ballet needed surtitles! However, if one ignored the narrative and watched from a purely visual and theatrical point of view—and I’m ignoring for the moment the implications of that idea—there was much to admire. Harbour’s choreography was brimming with ideas and I was especially taken by the fact that he had managed to imbue the choreography with the look of ancient Greek sculpture while also giving it a real contemporary edge. Stage concept and lighting was by the Melbourne-based lighting and design company, Bluebottle, and their designers made effective use of backlighting to create two worlds of action by at times turning what initially looked like a backcloth into a scrim. The work looked fabulous and the dancers looked beautifully rehearsed and absorbed in executing the choreography for maximum effect. But oh … that need for surtitles!

The closing work on the program, Baynes’ Molto Vivace, is a crowd pleaser, and to my mind an exercise in silliness, danced to a compilation of works by Handel. It was first seen in 2003. Dourly I have to say that I have never been a fan of this work but I laughed my way through it unable to do anything else when the woman behind me was almost hysterical with laughter from opening to closing moment. Laughter breeds laughter.

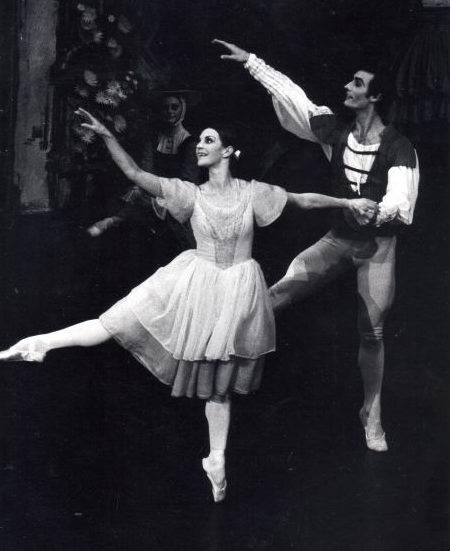

Leanne Stojmenov danced the leading role of the Lady but again like Martin in Edge of Night I found her performance beautifully rendered but a little cold. In the glorious central pas de deux with its exquisite lifts and soft, sighing movements, which for me is the raison d’être of this work, she looked perfect in an Alice in Wonderland kind of way. But thoughts of Simone Goldsmith, who created the role in 2003 and whose extreme vulnerability gave to the pas de deux a deep humanity, were hard to erase from my mind.

Michelle Potter, 28 November 2010