1 March 2018, Aotea Centre, Auckland

Reviewed by Jennifer Shennan

Aforethoughts and Afterthoughts.

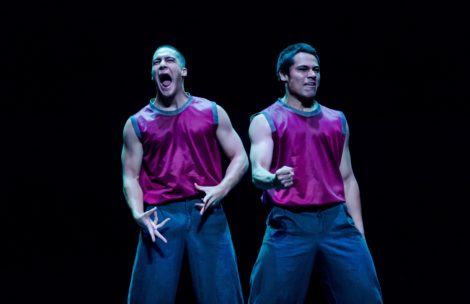

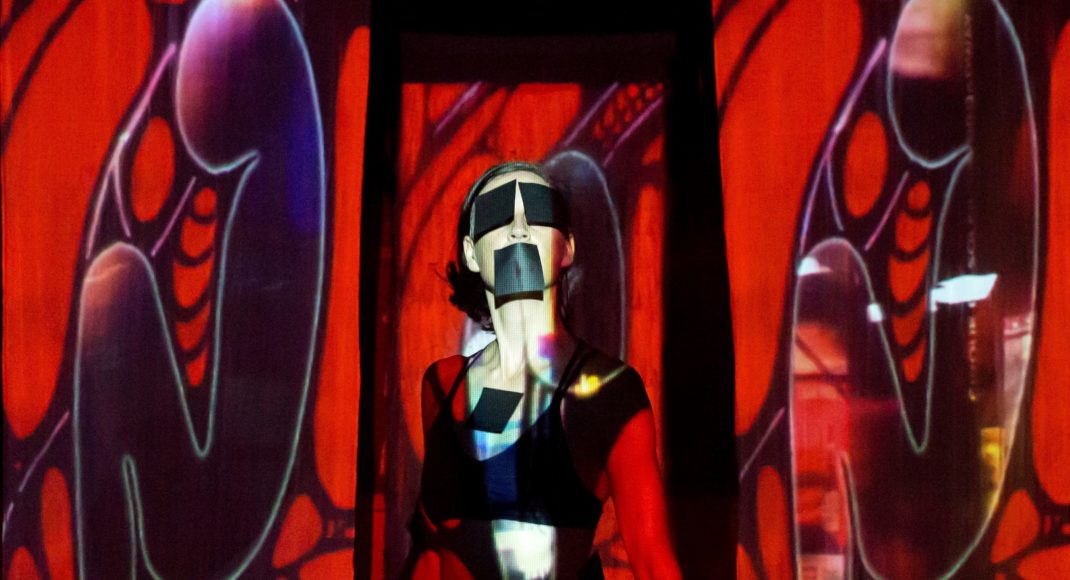

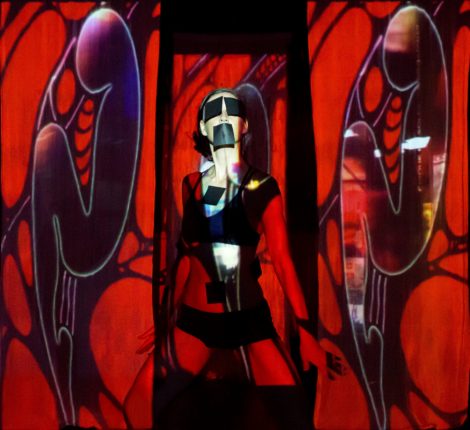

English National Ballet’s season of Giselle, in an acclaimed new production choreographed by Akram Khan, has just played at the Auckland Arts Festival. The setting has migrant workers stranded after a clothing factory closes down, and the clash between workers and factory bosses echoes the contrast of villagers and nobles in the 19th century ballet by Coralli and Perrot. Dancing is of the highest standard, the set is monumental, costumes inspired, lighting striking and the atmospheric music composed by Vincenzo Lamagna, scored and conducted by Gavin Sutherland, performed by Auckland Philharmonic Orchestra, makes major impact.

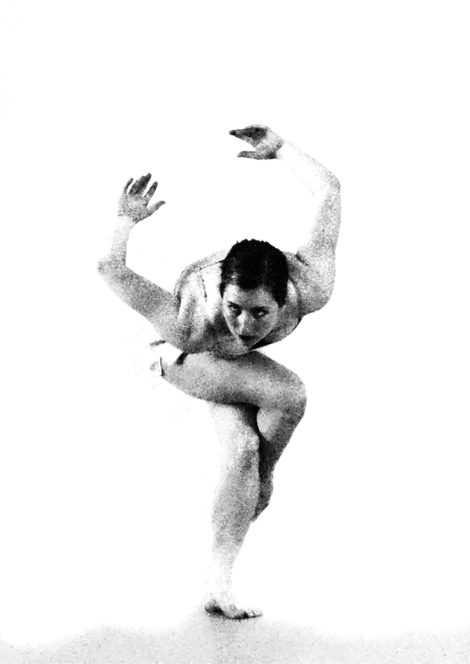

Many of us are thrilled by the contemporary relevance of this setting (Khan is Bangla Deshi. He works in the sophisticated milieu of European dance yet does not resort to any conventions and clichés of ballet). The gesture of Giselle’s arms down-stretched, hands slowly, so slowly, turning palms up as she asks Albrecht ‘Why? What is this about? What am I supposed to do? What are you going to do?’ The cast of co-workers repeat her gesture, as well they might. More Asian than European, more baroque than balletic, it is a telling opening to the story about to enfold.

Others are continuing to think about the echoes of the original storyline, the music, the choreography. There are about four fleeting fragments of ‘the old Giselle’ in the ‘new’ one, and they pull at your heart. Good. The ballet is engaging. No one is unmoved, no one denies the power of the production.

In 2016, Tamara Rojo, artistic director of the company, and herself still a performer in the lead role, commissioned this new version of the classic Giselle from Akram Khan, following a one-act work he had earlier made for the company. We have seen some of Khan’s work performed here by Sylvie Guillem several Festivals ago, and there are trailers aplenty on YouTube to give you the strength of his dance-making. It is poignant to learn that just after the Khan premiere season in London, there followed another season of the production by Mary Skeaping of the original ballet. Now that’s imaginative programming.

This is the first ever visit to New Zealand of English National Ballet, formerly known as Festival Ballet. A number of celebrated New Zealand dancers have been members of the company over decades—Russell Kerr, June Greenhalgh-Kerr, Anne Rowse, Ken Sudell, Donald McAlpine, Loma Rogers, Sue Burch, Martin James, Adrienne Matheson, Cameron McMillan among them. The company was for a time directed by Matz Skoog, former artistic director of Royal New Zealand Ballet, with Fiona Tonkin as assistant. Amber Hunt, New Zealand dancer, is currently in the company’s ranks.

Rosemary (Johnston) Buchanan, a leading dancer with New Zealand Ballet in 1960s, is now a patron of the company, and her artistic opinions are valued by ENB. It is poignant to witness the camaraderie and loyalty this company maintains for its heritage and history. The program essays are as good as you’ll find anywhere. It is reassuring that archivist Jane Pritchard writes about original and earlier versions of the ballet in a way that they do not need to be put down for new versions to be put up. In 1959, I slept three nights in the queue in His Majesty’s Arcade to buy a ticket in the Gods to see the Royal Ballet with Margot Fonteyn performing Giselle. The theatre and the arcade have since disappeared but the memory remains. Mindful of the achievements in that title role of such dancers as Margot Fonteyn, Patricia Rianne, Olga Spessivtseva, Carla Fracci, that ballet is not something I’m going to let go lightly. Fortunately, I don’t have to.

Old productions. New productions. There’s room for all. Michael Keegan-Dolan’s Giselle (by the Fabulous Beast Dance Theatre) was staged in Wellington several Festivals back—with Albrecht as a two-timing transgender line-dance teacher. (Well, you know the Irish). This man, whose Petrouchka and The Rite of Spring were staged in Melbourne in 2013 (the music played on two grand pianos on stage), is the fearless mover & shaker you won’t want to miss—though you might need a medicinal whisky, before the show and maybe after as well. He is arguably the best communicator about his choreography I have encountered, and he writes his own program essays. Stand by for his Swan Lake Loch na Neal due in the Wellington Festival mid-March. If you don’t like heat, stay out of the kitchen, but no one should write a feeble-minded review of his work.

There’s always much evidence of the well-to-do among ballet audiences, though we would of course claim that you and I are there for the right reasons. Everyone wishes for fairness in the workplace. There’s always been,and will always be uneven distribution of wealth in the world, no choreography will change that. We should think long and hard about this production of Giselle we have just seen, and maybe also about the time we first encountered it. Ask if any garment in your wardrobe was made in Bangla Desh, or in a sweat factory somewhere else? Also ask ‘Do all ballet companies, worldwide and close to home, treat their dancers fairly?’ since that would be a good place to start, if this remarkable production with its ethos is to be honoured.

Jennifer Shennan, 9 March 2018

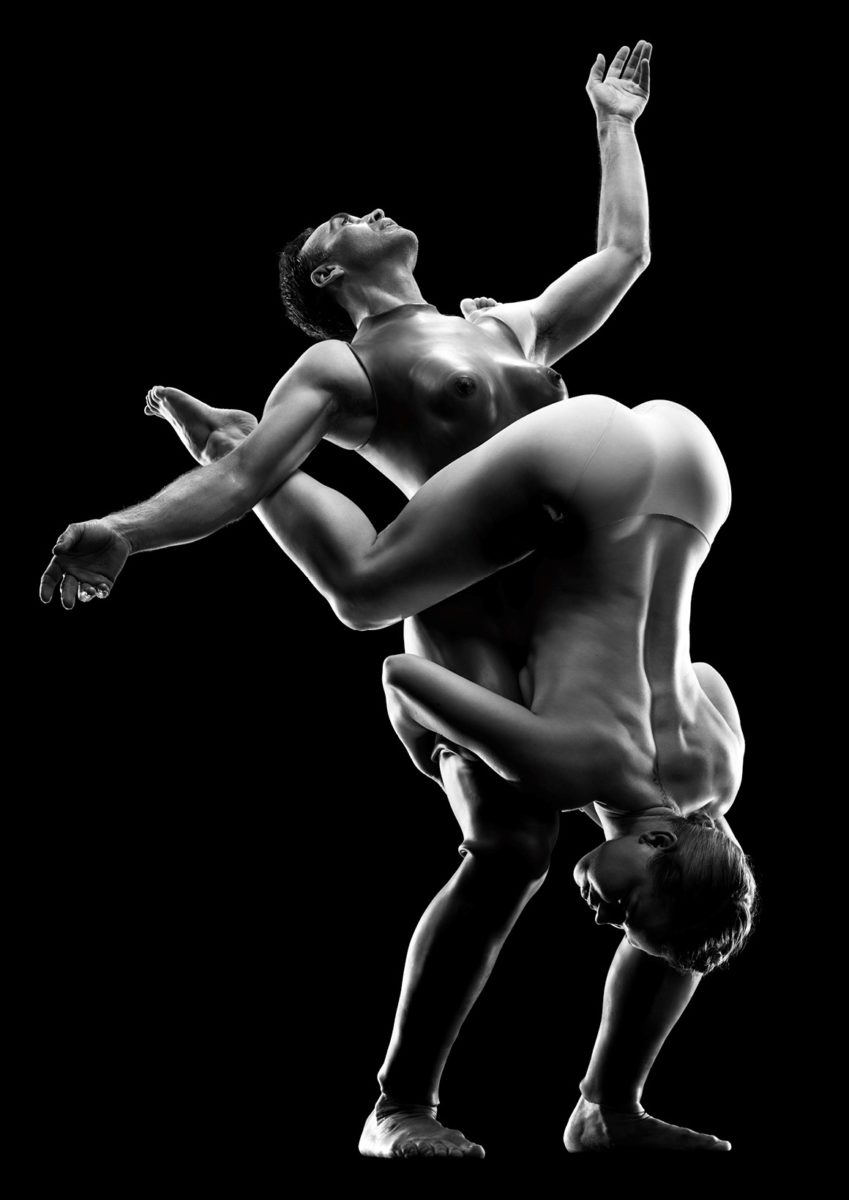

Featured image: English National Ballet in Akram Khan’s Giselle., Act II. Photo: © Laurent Liotardo

Follow this link for a review of Akram Khan’s Giselle posted in 2016.