Those who have been following posts on this site relating to Nina Verchinina may be interested in an article published in the most recent edition of Brolga: an Australia journal about dance (issue 34, June 2011). This elegantly written article, rather lengthily entitled ‘Designing for Nina Verchinina’s choreographic vivacity: a new light on Loudon Sainthill’s art’, is by Andrew Montana. It sheds important light on Verchinina’s choreographic exploits in Australia and suggests that gender may have played a role in the fact that, in Montana’s opinion, Verchinina’s ballets were never really given adequate showings in Australia.

The gender issue is an interesting speculation and perhaps will never ultimately be more than that. But the idea does have a certain plausibility and is echoed by the difficulties faced by Hélène Kirsova as she tried to develop her own company, the Kirsova Ballet, in the early 1940s in the face of competition from Edouard Borovansky. See for example my recent post on Kirsova, my article ‘A strong personality and a gift for leadership: Hélène Kirsova in Australia’ (Dance Research, 13:2, Winter 1995, pp. 62-76) and a shorter article in National Library of Australia News published in August 2000.

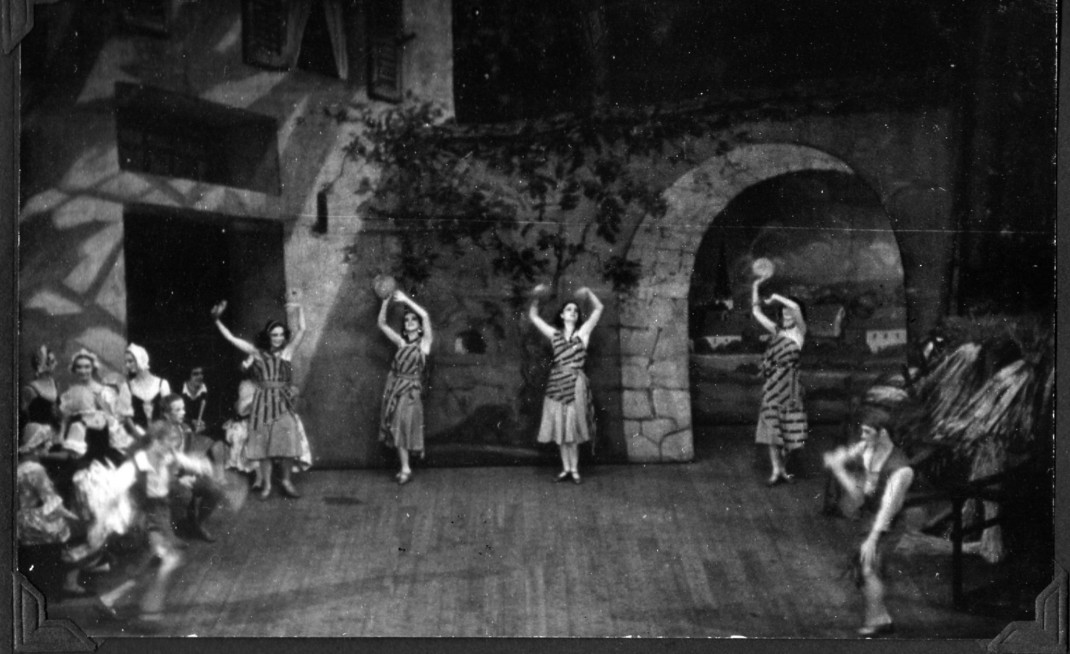

Montana is perhaps at his most eloquent when describing the drawings and paintings of Verchinina executed by Sainthill. But his article also develops further than has been done so far the story of de Basil’s design competition of 1940 won by Donald Friend, along with a number of other matters relating to the Original Ballet Russe in Australia.

As something of a side issue, Montana also mentions the Sidney Nolan designed Icare and notes that there is nothing to indicate that Sainthill was approached to design this work. This appears to contradict Brian Adams’ contention in his biography of Nolan, Such is life, that Sainthill had ‘already been commissioned by Colonel de Basil’ (p. 46) to design this work. Adams gives no source reference for his statement but I believe it does warrant more investigation. Adams goes on to say that Sainthill had been ‘edged out by [Serge] Lifar and [Peter] Bellew’ (p. 46) so there is potentially source material elsewhere other than in Sainthill’s archival collection, which Montana has investigated.

One error in the text needs correction. Montana notes that the cast of Verchinina’s Etude included ‘Lydia Couprina (Valrene Tweedie)’ (p. 22). In fact Lydia Couprina was the stage name of Phyllida Cooper, an Australian from Melbourne who had joined de Basil in Paris where she had been studying with Olga Preobrajenska. Tweedie danced under the name Irina Lavrova. As a side issue, however, there is a connection beyond nationality between Cooper and Tweedie. When Tweedie returned to Australia from the United States in 1950s she eventually bought the school in Sydney jointly run by Cooper and her then husband, James Upshaw. Upshaw later became Tweedie’s second husband.

Unfortunately this most welcome article from Montana is not available online, but it is worth following up in hard copy in libraries where Brolga is held.

Michelle Potter, 28 June 2011