4 December 2015, Carriageworks, Eveleigh (Sydney)

Seeing Ochres in 2015 after 21 years was a remarkable experience. More than anything it marked the astonishing achievement of Stephen Page and his team of artists. Through the creativity that has characterised Bangarra’s journey, Page has given Australian Indigenous culture a powerful voice. Ochres was an eye opener in 1994. Now it is a powerful evocation of all that Bangarra stands for.

This 2015 Ochres is not an exact rendition of the original. It is promoted as a ‘reimagining’ of that early show but is definitely close enough for those who saw it in the 1990s to feel they are seeing the work again.

As it did in 1994, the 2015 Ochres begins with a scene featuring cultural consultant Djakapurra Munyarryun, not this time painting up with yellow ochre, but singing a song, Ngurrtja—Land Cleansing Song–composed especially (I believe) for this 2015 production. He has, as ever, huge power and presence. He stood perfectly still for several seconds before beginning his song and the effect was mesmerising.

Torres Starait Islander Elma Kris, another of Bangarra’s consultants, follows with a section called The Light in which she, like Djakapurra Munyarryun had done previously, smeared her limbs and face with yellow ochre.

These opening scenes are followed by the four ‘ochre sections’—’Yellow’ inspired by female energy, ‘Black’ representing male energy, ‘Red’ showing male and female relations, and ‘White’ inspired by history and its influence on the future.

In ‘Yellow’, choreographed by Bernadette Walong-Sene, the women dance low to the ground. Their movements are most often flowing and they have an organic look to them. Deborah Brown shows her remarkable skills throughout this section. How beautiful to see a relatively classical move, a turn in a low arabesque with one hand on the shoulder for example, followed by sudden movements of the head as if she is curious about, and watchful for what is happening around her. Brown always looks good no matter what style her movements represent.

‘Black’, with contemporary choreography from Stephen Page and traditional choreography from Djakapurra Munyarryun, shows power and masculinity—hunters crouching behind bushes, warriors with their weapons sparring with each other. This section is also characterised by some nicely performed unison work.

‘Red’ has the strongest narrative element of the four sections. It focuses on four different expressions of male/female relationships moving from youthful dalliance featuring Beau Dean Riley Smith, Nicola Sabatino and Yolanda Lowatta to the final section ‘Pain’ in which Elma Kris cares for an ailing man, danced by Daniel Riley. But in between we can imagine other relationships. Domestic violence and addiction perhaps?

‘White’ concludes the program. The two cultural consultants, Elma Kris and Djakapurra Munyarryun, lead this final section and, with all the dancers covered with white ochre, a spiritual quality emerges from sections representing a range of concepts from kinship to totemic ideas. The choreography is credited to Stephen Page, Bernadette Walong-Sene, and Djakapurra Munyarryun.

Jennifer Irwin’s costumes are cleanly cut and simply coloured. Jacob Nash’s set, looking like long shards of bark, hangs in the centre of the space above a sandy mound. It is lit in changing colours by Joseph Mercurio. A score by David Page is evocative of the 1990s but retains enough power and emotion to feel relevant still.

The kind of fusion of contemporary and traditional movements we have come to expect from Bangarra’s dancers is all there and reflects the fact that Bangarra is an urban Aboriginal initiative with strong links back to its cultural heritage. And, while the dancers of 1994 were extraordinary (a list of the 1994 team appears in the program), the manner in which Bangarra has grown technically is also clear. Its dancers are spectacularly good and their commitment shines through.

Michelle Potter, 9 December 2015

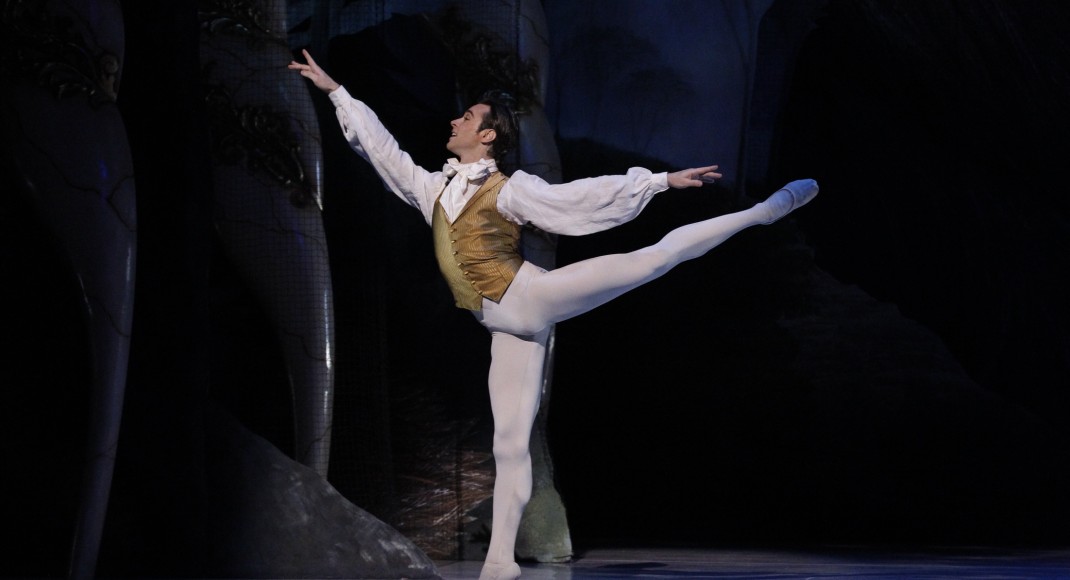

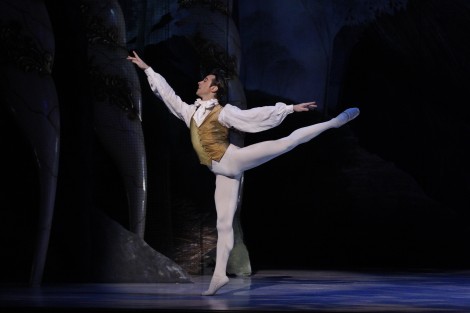

Featured image: Leonard Mickelo in a study for Ochres, 2015. Photo: © Edward Mulvihill

For more about Djakapurra Munyarryun follow this link.